In Charmed Chains, I chose some early restrictions to emulate some of how Yugioh plays, and over time I’ve been shifting towards different ideas of what I want to do with the game. I chose these restrictions because there are a lot of indie and industry collectible card games that emulate Magic The Gathering (Force of Will, Hearthstone, Lorcana, Final Fantasy, Digimon, etc) in whole or part, and very few that emulate Yugioh (Dual Spirits). When I started making this game, I was really into Yugioh (I’ve recently been swallowed whole by MtG Commander), and I was very much inspired by different facets of Yugioh’s design that I felt could be pushed further (having a defined grid and effects that are based on columns), as well as some aspects of Magic The Gathering (blockers getting a choice in whether to take damage with their creatures, or let it hit them directly).

However, these limitations have lead to some issues with granularity, which I’ve previously discussed. I’m worried that low granularity in creature costs will lead to homogenization in people’s decks, unless I either adopt a resource system more similar to most card games, or start to enforce more strict archetypal synergies, like Yugioh did.

To understand the issues I’m facing, first I’ll need to explain how the resources in Yugioh and Magic The Gathering work.

Resources & Costs

Yugioh, in contrast to nearly every single other trading card game, has basically no resource system. Magic the Gathering has Lands; Pokemon has Energy; Hearthstone has Mana; Digimon has Memory. All of these are high-granularity costs for cards, which usually build up over the course of a game and usually cannot be removed or disrupted by the other player. In contrast to this, Yugioh only has what’s in your hand, what’s on your board, and a single normal summon per-turn (and to a lesser, but still incredibly significant, extent, what’s in your deck and graveyard have become resources as the game allows players to pull from those more).

In early Yugioh, this normal summon built up over the course of multiple turns. A 1-4 level monster cost a whole normal summon. A 5-6 level monster cost two normal summons (one for a 1-4 level monster, one to tribute it for a 5-6 star monster). A 7 or higher level monster cost three normal summons (two 1-4 level monsters, one to tribute them). This meant that it could take many turns to get out your stronger monsters, assuming your board state wasn’t disrupted in the meantime. It also created a snowball effect, because if your board got wiped, you didn’t have accumulated resources to fall back on, and you didn’t get any type of compensation for your removed monsters.

Lets compare this with Magic the Gathering. In Magic, you are allowed to play 1 land each turn. This means if you never miss a land drop, you’ll gain one extra mana to cast spells with each turn. This means during early turns, there is briefly a resource crunch where your single land drop is of extremely high priority (like a turn 1 Esper Sentinel, Birds of Paradise, or Ragavan), but overall costs are allowed to be a lot more granular than in Yugioh, and comebacks are more possible, because your hand & board state isn’t your primary resource, your lands are.

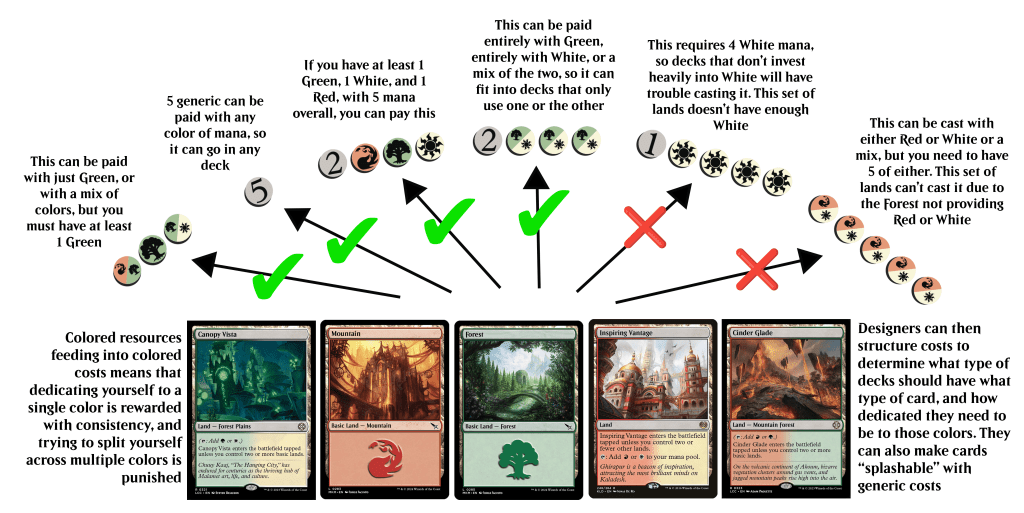

Magic the Gathering also makes costs more granular in that each spell can cost different amounts of colored mana or generic mana. This allows Magic to reward decks that focus on single colors with more consistency, and creates a basic system of requirement before a spell can be cast. A spell with a single colored pip requires a mana source of that color and thus can be splashed easily into other color decks, whereas a spell with many colored pips requires many mana pips of that color, and thus can’t be run easily in a deck that isn’t willing to commit.

Because Yugioh chose the limitations it did for itself, Yugioh literally had no options to diversify decks initially, and every early deck was some variant of beat-down and “good stuff” (staple cards that were good and fit into every deck). As the game progressed, it eventually chose to solve these problems by dividing the card pool into Archetypes (sets of cards that share a string in their card names and which all reference one another to create incredibly strong synergy) and focusing the game around your first normal summon and the combos you perform off of it, as well as your opponent’s ability to disrupt those combos.

Attack Power

Another element of granularity between Yugioh and Magic is the granularity of its battle stats. In Yugioh, normal summonable monsters can have attack values between 0 and 2000. Since attack values rarely use the tens or ones digit, this is more like an attack of 0 to 20. By contrast, a 1 mana creature in Magic can have a power or toughness between 0 and 4, but most often it will be 0 to 2. Only 31 cards in the entire game have 1 mana value and a power of 3 or greater, and 8 of those cost mana to transform (one of those 8 is a modal dual-faced card, so it’s technically not a 1-drop at all). Most of the rest have some special condition before they gain that power (death’s shadow, phyrexian dreadnought, consulate dreadnought, and usually require other previous investment of mana before gaining that power).

This means that a card you can play on the very first turn of the game in Yugioh can have an INCREDIBLE amount of granularity when battling other monsters. And in Magic, creatures have a very low amount of granularity for fighting one another, making trades more common, and making the move from 1 to 3 power or toughness incredibly substantial. This means that trades (mutually assured destruction) are a lot more common in MTG than Yugioh, so MTG has a lot of keywords to allow creatures to bypass one another, such as first-strike, flying, menace, etc.

Charmed Chains

In Charmed Chains, I elected to follow Yugioh’s primary system of cost: Sacrificing monsters & Summon Limits. Unlike Yugioh, I’ve added a resource system inspired by the Trinity format: up to 3 “Stardust” counters (basically Mana), which are required to summon familiars using sacrifices. This means that you have a resource other than just your board state and hand. Given the way I designed the combat system (3 lanes, attacker moves two familiars, defender moves one), familiars naturally have a type of evasiveness that they don’t have in MTG or Yugioh, meaning that I can strike a middle-ground between MTG’s mutually assured destruction and Yugioh’s run-away snowballing of higher attack power monsters. This means that familiars can stick around longer, and you are less likely to lose your board state and therefore all your accumulated resources towards more powerful familiars. In addition to this, when your opponent destroys one of your familiars, you are compensated with a draw, making it more difficult to fall behind.

However, I’m running up against a very similar limitation to early Yugioh and some of MTG’s current formats: The only form of cost differentiation I have between cards is how many sacrifices/stardust they cost. My original intention with this game was to create a combo oriented game in much the same way as modern Yugioh, but using stardust to put the brakes on how crazy combos could be, much like the Trinity format mentioned earlier. Similarly, in MTG, the modern format is currently overrun with extremely efficient low-cost value engines (Ragavan, Ledger Shredder, Orcish Bowmasters, Dragon’s Rage Channeler, etc).

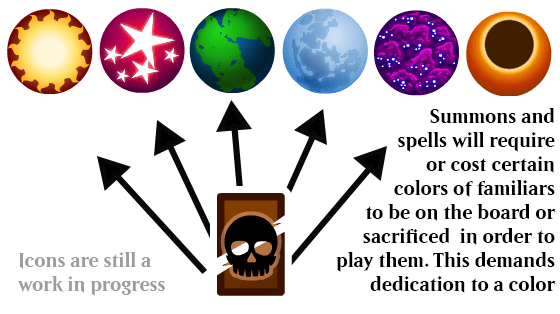

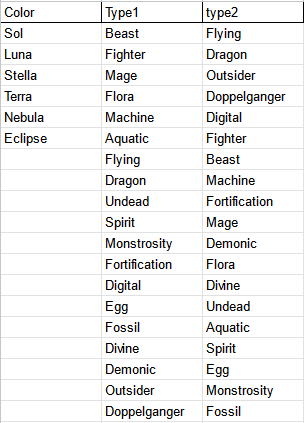

I do have a color system in place to avoid some of the homogeneity of early Yugioh, but it’s entirely possible that the metagame will converge on whatever familiars generate the best value, or simply have the highest attack power for a given number of sacrifices, much like MTG and early Yugioh. This means I’ll probably have to tie value engines to synergies, and need to be very careful around cards that simply have a sacrifice requirement and nothing else. And I’ll need to be very careful to keep these synergies weak enough that they don’t solidify into archetypes like the Yugioh and Digimon TCGs.

For the attack and defense values, I feel like I really lost out by not including MtG’s system of power and toughness, and instead opting for the winner-takes-all system of Yugioh, but these are the limitations I chose for myself, and I’m going to push them in the most interesting ways I can.

In Charmed Chains I elected for single cost familiars to have an attack power between 0 and 50, (0-5 effectively), meaning that familiars you can play on the first turn have a lot more granularity in their attack power than ones in magic. The most powerful familiars in the game cap out at 120 attack. Since the starting life is 600, this means a 30 attack familiar is the equivalent of an MTG 1/1, and a 120 attack familiar is the equivalent of a 4/4. This means familiars operate on a similar “clock” to MTG creatures, but there’s a much wider range for familiars to attack over one another without creating standoffs.

Between all these decisions, I hope to create a game in which familiars have more survivability than monsters in Yugioh, but there are less stand-offs than in Magic. On top of that, since combat is winner-takes-all, like Yugioh, I’ve been looking into keywords that create more ties in combat; where both familiars survive, or both familiars die. Since MTG has keywords that aim to break deadlock in a system with a lot of natural deadlock, I’ll want to introduce additional deadlock to compensate for being more “swingy”.

The Focus of Charmed Chains

Aside from that, I’ve decided that my focus for the game is going to be on combat specifically. Combat and combat tricks are extremely “fragile” in the design space of card games. Combat tricks like Rush Recklessly were extremely influential in Yugioh’s early days, when the most important thing printed on a card was how many attack points it had. Combat tricks are only really useful in Magic in the Limited format, where you draft cards and have little ability to build optimal decks, but combat tricks are in great supply as mana-efficient card-inefficient ways to win combat, which is more emphasized in the Limited environment. Combat tricks rarely see play outside of limited, usually only when they’re part of a wincon (Berserk onto creatures with Infect), or they naturally make up for card inefficiency by being a cantrip (Wildsize), or providing ongoing value (Embercleave).

Luckily, my game system naturally affords combat tricks to a certain extent, due to its lane system, allowing familiars to evade one another. And familiars can change from attack to defense position or vice versa as their move for the turn. This is a type of built-in combat trick, and it could potentially be part of the key to making the game work overall.

If a player could make a deck that contained only the cards they needed to win, and play them on the first turn, they would. In other words, things like hard removal, card draw, board state advantage & resource advantage are all things that overshadow the comparatively less influential back-and-forth mechanics of combat. In order to build a game that focuses on combat, the designers need to be extremely careful to safeguard against these common staples of card game design. Cards like Feather, The Redeemed; Soulfire Grand Master; and Lier, Disciple of the Drowned can help recur combat tricks through buyback or flashback types of effects, but even making up for the natural tradeoff of combat tricks, having a bit more power than your opponents during a given combat isn’t nearly as effective as hard removal, card draw, advancing your board state, or a win condition. If you want combat to be good, these other things need to be bad, and/or obtainable only as a direct result of combat tricks. I’ve built a Magic cube that tests these concepts out, which you can see here.

Additionally, after playing a lot of MTG Commander, I’m struck by how much deckbuilding variety you can achieve in that game, and how loose and flexible decks can be (of course, ignoring the type of optimization that goes into cEDH, which centers on a very small card pool). Yugioh got stuck optimizing narrow archetypes, but Magic manages to have more loose synergies by focusing on weaker synergistic buffs for creature or card types. Digimon is a good point of comparison as another archetypal game, but not nearly as overwhelming as Yugioh. A large number of non-archetype cards end up in decks, and not simply as engine pieces. Notably, no card in Digimon can search your deck, and effects that buff your digimon’s attack power are still very common.

In conclusion, I’m going to have to think and work very hard to make this whole thing work out. Hopefully I can pull it off for the beta phase. In the meantime, I’m still compiling solutions and thinking through how exactly all these pieces will fit together.

the desk of ygo is always empty just because its destroy is cheap.

u r right that number of cards is only source of ygo, generally ygo need the same num of cards to stop the a num of cards(if suitable, as we know PRODIGY WAKAUSHI need two handtrap to counter if not ghost rabbit)

LikeLike

The deck empties out fast because it’s a smaller deck than other games and you can summon and search from it, so you’re pulling tens of cards out of it on turn 1.

Yeah, 1 for 1 trading on card advantage is pretty common and keeps things balanced, but also card games and games in general are more fun when there’s disparity in one trade for another. Having a low cost for a narrow interaction, or a high cost for a powerful interaction are common.

I’m hoping to make a game where creatures are more survivable.

LikeLike

i prefer cost type game because it rewards interaction, if two mana always equal to three damage or three health creatures, then game becomes cost fight cost, its fair because cost convert to damage/health then enter to gameframework, but in ygo, card directly enter togameframework,so if you card dosent suit the table its useless, and you first hands decide the game.

LikeLike

I think Yu-Gi-Oh needs stronger mulligans personally. Bricking is less common than magic, but completely unrecoverable.

I think the solution to Yu-Gi-Oh’s problem is to slow down the pace of the game, give players more card selection, both in their opening hands and throughout the game, and to leverage more hidden information.

As the game becomes more rigidly deterministic, it becomes about optimizing combo lines, and calculating to avoid misplays. If players have less real decision points then the game really is about just your opening hands.

Magic also has the problem that a 2-mana spell can frequently destroy an 8 mana creature. Ward was introduced specifically to deal with this disparity, making it more expensive to remove higher investment creatures.

While this kind of equivalency in rate of card advantage or mana advantage makes sense from a balance perspective, obviously games are only interesting when there is disparity and asymmetry.

LikeLike

whatever I dislike an escapeable battle system. battle should have a accessable result.

to me, a more surviveable creature system will be setting limit to battle damage. creature has 1-10 atk and1-3 stma.if the bigger attack the smaller, only the smaller loss 1 stma. if the smaller attack the bigger, both of them loss 1 stma.

whatmore, the ygo monsters hard to survive to next turn is also a signature that they are really dangerous , named terminals, with 2 speed destory, counter or even blocking ability and resistance.

ygo is really a game competed by how big terminal desk is and how easy to make it.(but some are not, like Runick)

to mtg, not such a terminal creatures, the dangerous creature appears more slowly if dont use some cost trick combo

LikeLike

if creatures are as dangerous as ygo but you make they more survivable, it just ruin the game.

LikeLike

Sorry, it’s a little hard to understand your word choice and sentence construction.

My answer to stamina is shield tokens, which can tank a hit for a creature, but which are removed if that creature battles, or would be destroyed. So basically they work like the stamina system you describe.

By terminal, do you mean towers? Like Qliphort Tower?

Yeah, in Yu-Gi-Oh you combo to end-board on your first turn usually, and the mana system in MTG limits that. I have a system limiting that, explained in the article.

LikeLike

I’m too lazy to organize my words. Suppose you have a creature with high attack power and I have a creature with low attack power. If you use the creature with high attack power to actively attack my creature, your creature will not be damaged, but my creature will lose one stamina. On the contrary, if I attack your creature with a creature with low attack power, both my creature and your creature will lose stamina.

LikeLike

“translate from google”

LikeLike

Yeah, that’s how shield counters work in my game more or less.

LikeLike

if you are ready, send an email to me, after 3-15 I will have some time to make a program template, but better you have a real clear document.

LikeLike

or just add my github account SciHomo

LikeLike

LikeLike