When you get ‘stuck’ in a fighting game, like, say, when you play against a character you don’t know how to fight and you just don’t understand how to deal with them because all of the moves of that character seem to have priority or the char. just has better ledge game (in SSB) or this one move you just don’t know how to counter, what is your process for figuring out how to deal with or counter this character (or a certain tactic)?

I almost never get stuck, because I generally have a good understanding of how the systems work. Mewtwo teleports at me, I know I need to have a hitbox on the spot he’s about to appear before he’s there. I’ve worked out plenty of anti-jank tactics versus snake’s grenades and mines. I’ve spiked lucas players trying to tether to ledge for free. I’ve uppercut dhalsim’s limbs. I’ve faultless defense’d Faust’s blockstring pressure into his unblockable (so he can’t run up into it as fast because FD pushes him away further, and since it’s an unblockable, I can’t jump out like with a throw). I pointed out to my friend in KoF98 that Athena’s hard autocorrect divekick was probably really unsafe on block, because it wouldn’t make sense to be safe on block (turns out, yeah it’s really unsafe).

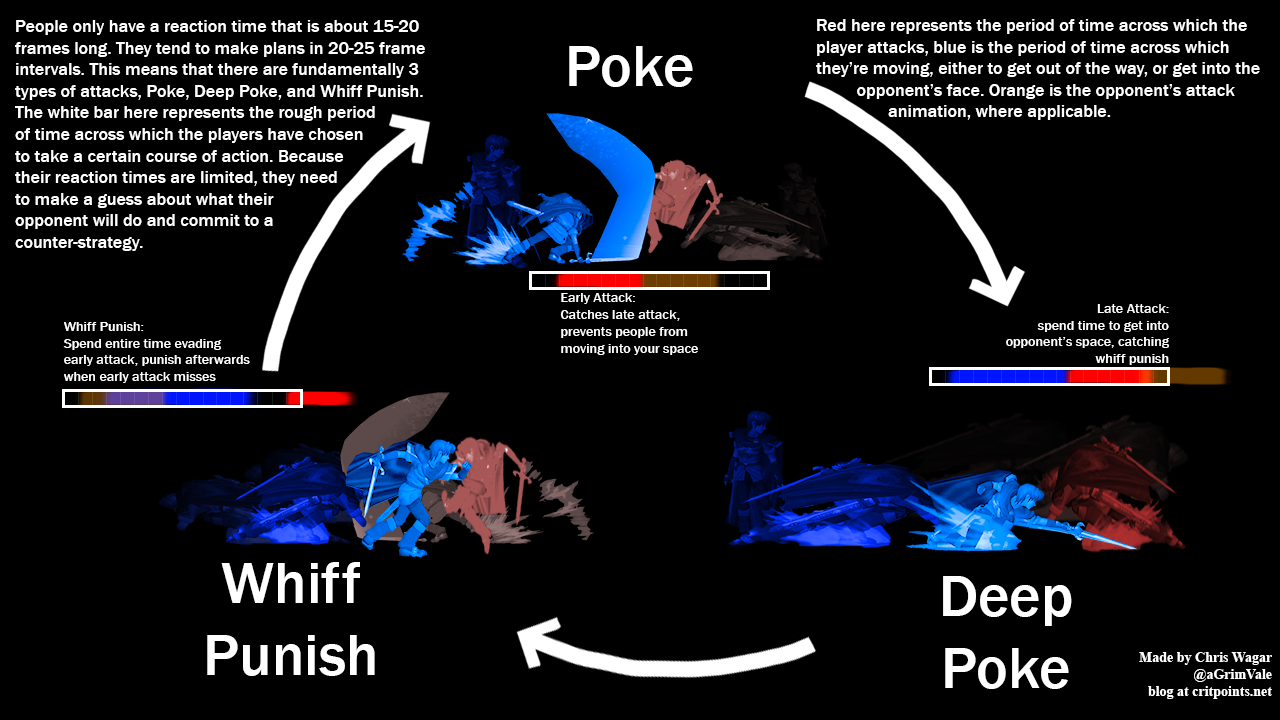

Everything always has a counter. Either you hit them before they do it, you punish them after they try to do it, or hit them in the middle of it. Good understanding of the system as a whole, good expectation of the trends in the system (like knowing which moves are probably unsafe), being able to recognize what happens with the move in different situations, and thereby being able to diagnose the move’s weakness. Like Dudley’s cross counter in third strike doesn’t counter low attacks. I never read a guide mentioning this, I just played a lot and noticed it as I played.

If I’m having trouble with a character, I usually look up guides for the character I’m having trouble against. Learning how they see things from their perspective is helpful because it also includes their weaknesses and what they need to watch out for. Investigation into framedata can be helpful too, as it was with Necalli in SFV, learning that his blockstrings into the stomp special are tighter with the light stomp, but more disadvantageous on block, and have a gap with the heavy stomp, but more neutral on block.

There’s a large number of resources you can potentially look into in order to learn how to beat characters for any popular fighting game.

I recently played PM after a long time and for the first time against a player and how the FUCK are you supposed to fight Marth? ALL his moves have priority over everything I did (not to mention longer range). I could only beat the player using Charizard and his giant-ass hitboxes with flame-tip and claw sweetspots.

Hahaha, that’s funny. Marth has an advantageous matchup against charizard, because charizard’s tail isn’t disjointed and marth can just whiff punish slash it, also because marth gets good combos on floaties and can space against Charizard in shield really well (and charizard already suffers against shield pressure).

I play with the second best Charizard player in the world actually, and as you may know, I main Marth.

Some key things to remember are, priority doesn’t apply to air attacks. Air attacks cannot clank, so forward air from Marth will cut through your hitboxes.

Marth’s big weakness is that he doesn’t have any attacks that come out particularly fast, and his attacks don’t have great recovery. His fastest ground attacks are jab, down smash, and Up B, all coming out on the 4th or 5th frame.

If your friend is spamming SH double fair, you can either move out of the way, then hit him right when he lands (charizard has an amazing dash dance) either with a grab or forward tilt (charizard’s forward tilt is amazing), or move in closer to him and shield on the spot where he’s going to land, so he’s forced to land in your shieldgrab range. These apply to any character.

Marth’s dash attack sucks, can be beaten by shieldgrabbing or just letting it whiff and punishing it.

Marth’s down tilt is his best neutral move because it has amazing IASA frames, so it effectively has a short recovery. Also has a reasonably fast startup of 6 frames. He can usually dash out of it before getting shieldgrabbed, but it’s still susceptible to whiff punishing.

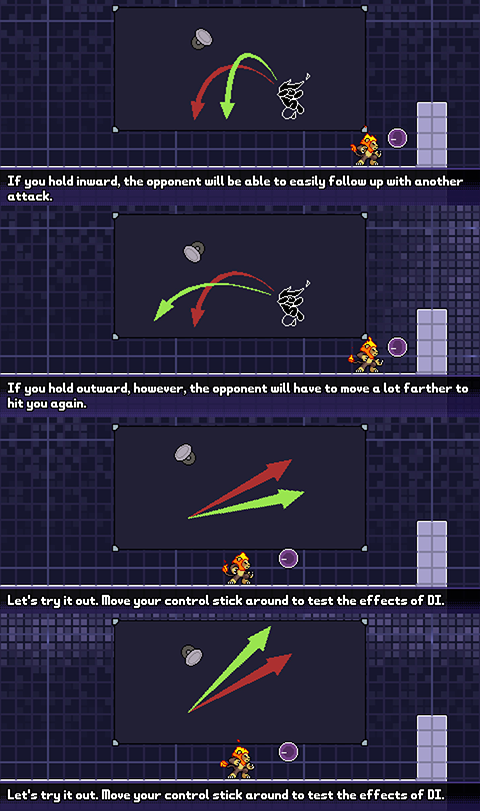

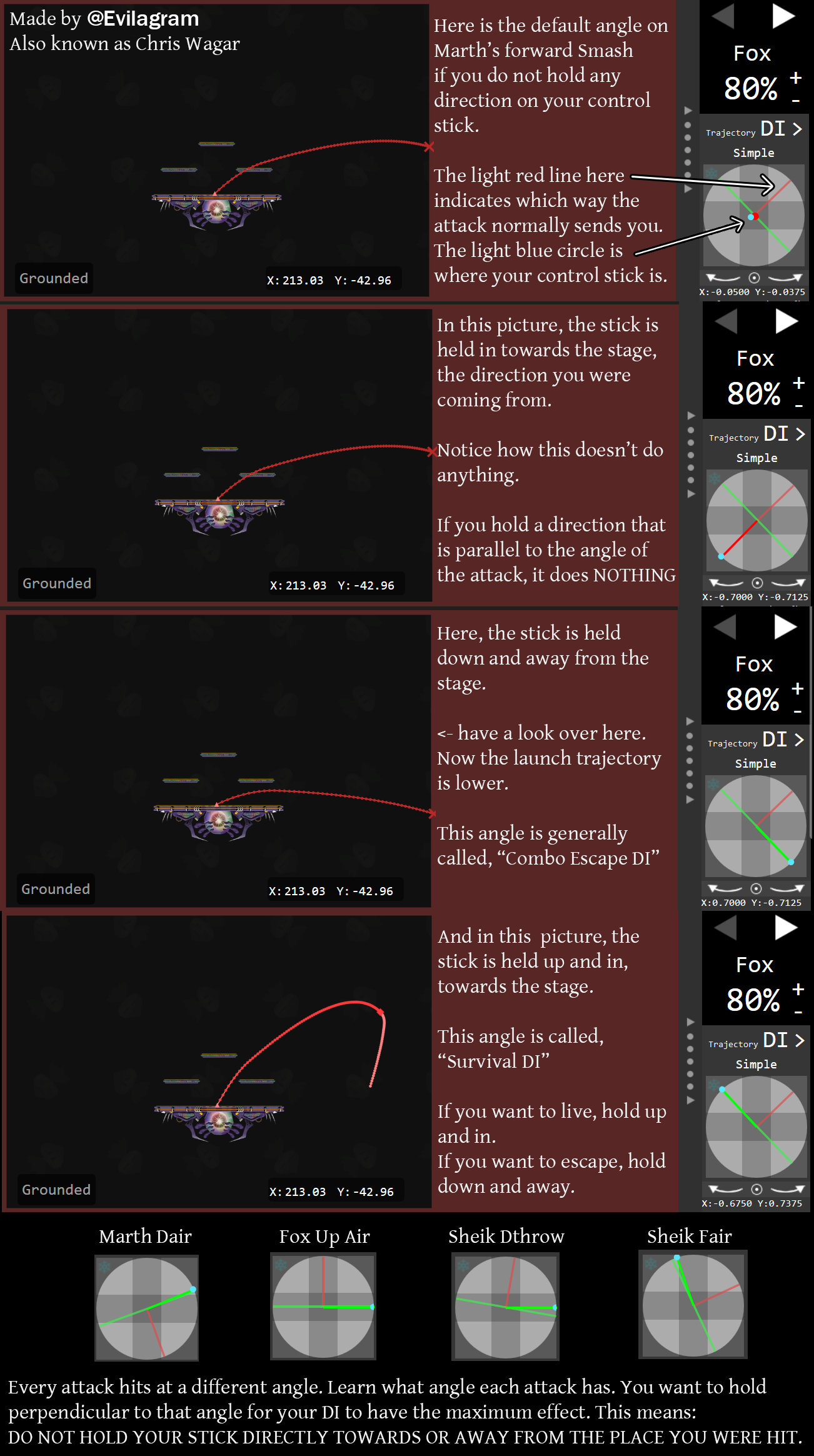

You want to DI marth’s fair chains out, to avoid getting spiked. His up tilt and dash attack have a trajectory that sends you in at Marth, so you’ll want to DI down and in at Marth. Those three moves are how he sets up most of his combos. His grab is normally useful in combos, but charizard is so heavy it rarely comes into play. Just be sure to DI down and away from him when he forward throws you. On lighter characters, he can also down throw as a DI trap into fsmash, so you’ll have to guess which way to DI to avoid getting fsmashed.

His fsmash by the way, has almost no shield pushback, so you can shieldgrab it no problem. If he’s out of range, then let him whiff the fsmash and you are totally free to run in and do whatever you want to him. I do this to a lot of marth players I know are worse than I am when I feel they’re about to fsmash. Just wait at the very edge of their fsmash range, let them miss the attack, dash in an grab.

As charizard, watch out with your dash dance, your tail lags behind you, and can be slashed if you’re not careful.

Any tips for Ganondorf in PM? I wsa using him and couldn’t do jack to Marth until I picked up Charizard. I’m surprised Charizard has a bad matchup against Marth, though that’s probably because the other guy just wasn’t that good. Also the setup was laggy so that might have given fatso charizard the advantage.

Ganondorf, he’s also on the lower tier side like charizard, hard to say how his matchup against marth goes. I think marth still has the advantage. Luckily I alt Ganon. Ganondorf is all about single hits and spacing, Marth is also about spacing and has disjoint. Ganondorf kills in a few hits, Marth has nice combos, though none of his grab setups work on Ganondorf because he’s too heavy.

Basically, you want to hit him when he misses you. Ganondorf gets great followups off his down throw versus marth. At lower percentages, he can regrab (marth can DI forward or behind ganondorf, so turn appropriately to catch him). At higher percentages down throw gets guaranteed followups into fair or bair depending on DI. Ganondorf can’t move that well to whiff punish grab marth, but he can move in on marth forcing him to land in bad positions and be open for a shieldgrab.

Ganondorf has a nice jab, much faster than any of marth’s moves (one of marth’s central weaknesses is that he has no good fast moves), so that can be useful in a pinch.

Ganondorf’s down B can outprioritize all of marth’s grounded moves, but it loses hard to aerials or shield. Side B is good for shenanigans, when you scare him into shielding you, or if he tries to shield while on a platform and thinks he’s safe (since normally you can’t grab people unless you’re on the same ground they are). Air version gets better followups, ground version has better range and can avoid attacks like Dudley’s short swing blow. Ground version can be teched before ganon can do anything about it, air version does a small juggle which ganon can usually at least jab off of before they get a chance to tech. Up B is also a grab and can shenanigan people in much the same way, grabbing them when they think you don’t have the grab option.

Most of the matchup is going to be moving carefully, and poking at marth before he swings or waiting for him to miss a swing and poking him. You’re just gonna have to get used to reading a lot harder and winning neutral more with worse tools. Ganon has nice range on a lot of his attacks, technically better than marth’s on fair, you need to get better at figuring out when he’s going to attack, avoiding it, and hitting him back. You don’t need to win neutral as many times as marth does, because you get bigger rewards for winning neutral.

I beat a guy playing falcon yesterday every single time while I played Bowser. In Melee. If you have good enough instincts, anything’s doable.