I believe that there’s a spectrum of Riddles, Puzzles and Games, which each play on a similar root desire of, “Try to make the thing happen,” but with different emphasis. Puzzles and Riddles are subject to the spoiler effect. Once you know the solution, it’s not a question of whether you can beat it or not, you can always just produce the solution, unless you forget it. This also means that someone can tell you the answer and there’s no challenge anymore. Games tend to emphasize tests of skill, which cannot be overcome simply by knowing the answer.

A Riddle is essentially asking a question to which an answer must be reached through induction. A Puzzle creates a system of logic from which an solution can be deduced. And a Game creates a system of interactions which must be manipulated to produce a positive outcome from many possible inputs or “solutions”. You could also probably fit Contest in there, which creates a single interaction that must be manipulated over a certain threshold.

Riddles essentially have a specific answer and a hint as to what the answer is. The hint can be more clear or less, but the key defining feature of a riddle is that the relation of the hint to the answer isn’t definitive. You can’t entirely logically prove that a given answer is valid or invalid. The answer must be reached through the process of induction, and there is binary check to see whether or not it matches

Who makes it, has no need of it.

Who buys it, has no use for it.

Who uses it can neither see nor feel it.

What is it?

The answer is a coffin (maker isn’t dead, neither is the buyer, dead guys can’t sense). Or mind-numbing drugs (drugs are bad, nobody needs or has use for them). Or therapy (therapists don’t need it, insurance pays for it, it’s not physical). Or you could probably come up with a lot of other answers.

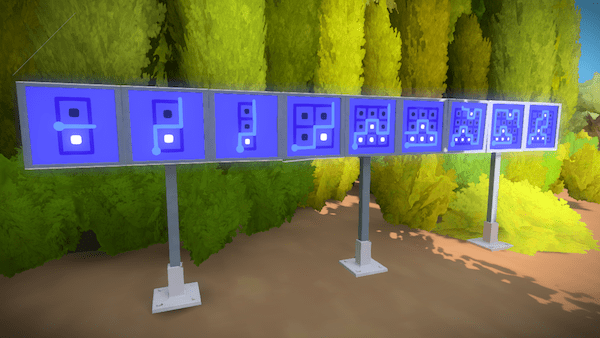

Puzzles have a deductive logic. If you understand the axioms that the puzzle is built on, you can work through a solution and logically verify that it is correct, without asking the game for the answer. Puzzles typically have a small number of valid solutions, but this isn’t necessarily the case. In The Witness, the game starts with the axiom that you draw a line through the boxes in each panel, and the line cannot cross over itself. The puzzle is complete when the line connects to an end point. As the game progresses, it introduces new axioms that are taught through a series of panels that grow in state space and complexity, to guarantee that you understand the rule you’re being taught, such as “squares of different colors must be on different sides of the line” and “tetris shapes must be enclosed by a line that contains blocks exactly matching the combined dimensions of each shape enclosed”. This gives the player a rigor and certainty in their deductive logic for solving puzzles, which is what makes them puzzles instead of riddles.

Games can be framed as puzzles. The search to solve classic games like Connect 4, Checkers, and Chess approach these games as big deductive puzzles. You can also look at TAS (Tool Assisted Speedruns) as a puzzle to find the path to the end of a game in the least number of frames.

Where games differ from puzzles is that games tend to accept a wider range of solutions; the player is given a larger fault tolerance. Games also frequently include not just tests, but measurements and metrics of physical execution or mental processing. And games dynamically vary both the solutions and the nature of the puzzle in response to player input, or random number generation so that different players are each presented with a unique version of the problem to solve, preventing players from memorizing or spoiling the solution. I wrote about methods for accomplishing this type of dynamism in my Skill Test article on GameDesignSkills.com. By giving the player fault tolerance and dynamic changes in the state space, you afford the player choice. Games are about Interesting Choices instead of static solutions, like puzzles or riddles.

The ending of The Witness presents you with a randomized series of puzzles that you are timed to solve. This is more game-like than the rest of the game, because your puzzle-solving skills are being tested under time pressure and input RNG is utilized to present you with a unique challenge that you cannot memorize or spoil.

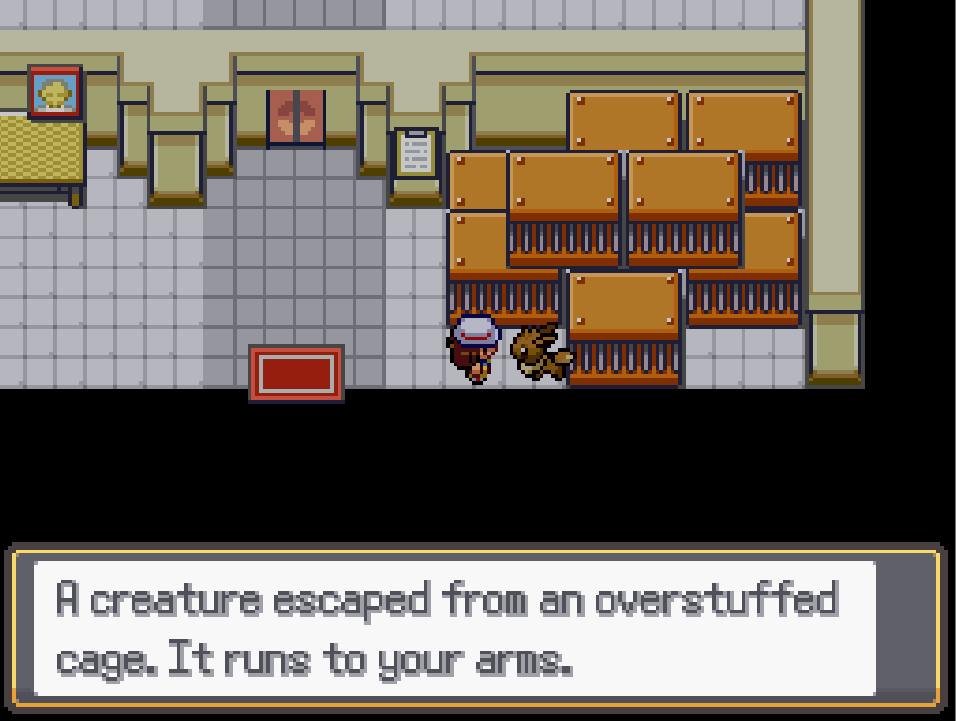

Pokemon is a game, because you have a great freedom to choose which moves you use, which Pokemon you catch, how you level them up, and the game will present you with different challenges based on your choices, and random chance. Pokemon can be made into a puzzle, such as in Pokemon Escape Room ROM Hacks. In these hacks, you have a very limited selection of Pokemon, and you are pit against a very limited number of trainers and wild battles, which makes escaping a test of your Pokemon knowledge and deductive problem solving abilities. In other words, your choices are constrained in favor of finding a definitive solution.

You can see something in the middle of the spectrum between puzzle and game in the form of Pokemon Salt & Shadow. This ROM hack disables leveling, only lets you use the Pokemon Center 13 times, and has limitations in the Pokemon and moves you can acquire with a metroidvania styled map. This means that it’s closer to a puzzle, because it’s more specific about which choices are valid solutions, but it’s still not quite a puzzle because it doesn’t mandate that there is only a small number of correct solutions and there is still a fair amount of dynamism introduced through the random chance inherent in the Pokemon battle system.

This room in Ocarina of Time contains a riddle, which is commonly mistaken for a puzzle. In Dodongo’s Cavern, there is a large stone block surrounded by bomb plants, with a gap in the line of bomb plants at the center of the block. If you place a bomb here, it will detonate both lines of bomb plants, causing the block to collapse into a set of stairs. This requires a leap of intuition that the developer wanted you to place a bomb here, rather than any deductive connection between previously established rules. The block cannot be lowered except by placing a bomb at that spot, and this interaction is not repeated anywhere else in the entire game. This room has a bespoke script and cutscene animation that is specific to just this interaction, making it definitionally a riddle. I’m not fond of this. I find it kind of thin. It’s a wasteful way to develop a game, which only got more and more extreme as the series progressed, until Breath of the Wild chose to pursue a strategy of multiplicative design instead of ad hoc design.

Adventure games, such as point and click adventure games, are generally composed entirely of riddles. You have “locks” that give you a hint, and then you have to match them to a “key”, usually an item in your inventory, but sometimes a written answer or performing the correct action. At their best, riddles can have a clear and consistent logic, while also concealing their answer, and very clearly corresponding to the correct answer once you’ve discovered it. At their worst, riddles can be random bullshit that you need to check a guide for.

A lot has been written about the death of adventure games. Personally, I would point out the riddle-heavy format. When the only form of obstacle in a game is hints to solutions, then it’s hard to really scale up the challenge as the genre evolves. The only way to make a riddle more difficult is to make the connection between the hint and the solution more obtuse, but because riddles aren’t dependent on deductive logic there’s no guarantee that there’s any discernible connection between the hint and the solution. In other words: Riddles have no guarantee that they’re fair.

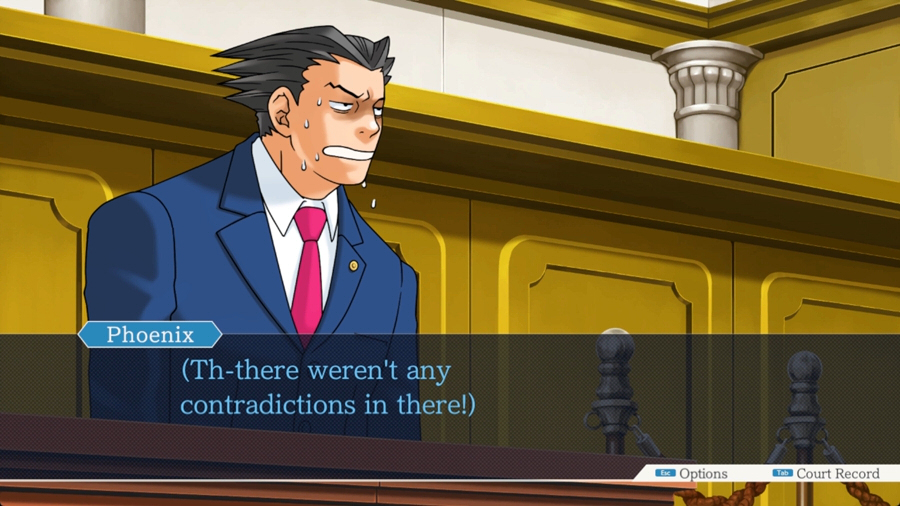

A good way to make a riddle fair is by establishing consistent criteria for a correct answer that can be logically extrapolated upon. Phoenix Wright has a clever way of doing this: Pointing out contradictions. Contradictions can be extremely subtle, yet it’s (almost) always clear what is a contradiction and what isn’t. Obviously Phoenix Wright isn’t always the best at this, but most of the time it’s pretty good about creating contradictions that are difficult to pick up on, but are clear in hindsight.

Puzzles, like riddles, aren’t about making interesting choices or testing execution, so much as they’re about creating a system of logic based on certain axioms and attempting to reason about how the system behaves to produce a solution from a small set of discrete answers. Riddles are less than that, not having a system to reason about, just the hint about the hardcoded answer (meaning, the answer is simply set to be what it is arbitrarily, not dependent on anything else). Puzzles can have hardcoded answers, but more frequently they’re a system set up to only allow a certain solution.

I think that riddles and puzzles differ from games. I don’t think they’re all quite the same medium and therefore I think they need to be judged more on their own terms. We still have the big colloquial label “game” for digital entertainment software which can encompass adventure games or puzzle games, but in a more strict sense, they’re not “games” the way that dodgeball, Mario, or 20 questions are. Depth is something I ascribe to be a positive quality for games, but a large differentiated and relevant state space usually doesn’t make a puzzle better. A big state space prevents puzzles from being brute forced, but it doesn’t add richness and texture in quite the same way that they do for a game, where depth enables interesting choices.

As said at the start, this is a spectrum. Something can be more riddley, more puzzley, more gamey, or somewhere inbetween. I previously discussed the examples of Pokemon Salt & Shadow, and the ending of The Witness. Catherine has elements of both game and puzzle, as stages have multiple solutions, but do emphasize a limited set of solutions. Some stages are designed to be more about interesting choices than finding a specific solution (this is demonstrated in the competitive versus mode). Plus there is a time limit, which makes the puzzle a test of your ability to process quickly. Obviously games have the space to combine all 3, as Zelda frequently does, and God of War has taken up in recent years.

Zachtronics games or “Zach-likes” (also called Factory Games) are also something strange that isn’t quite a puzzle but is very puzzle-like. There is a saying about Zachtronics games, that they are “problems”, not “puzzles”. Zachtronics games are about building automata that take an input and return a specific output. You are trying to discretely deduce a solution to a problem with an axiomatic set of rules, but there is a much wider set of solutions and when you complete the problem you are ranked based on different metrics for your solution, such as how much time it took, how many parts you used, the area used up, the cost, and so on. This is compared on a histogram to other players, challenging you to find a better solution.

Interestingly, I don’t think that “Action Puzzle” games like Tetris, Puyo Puyo, Panel de Pon, or Magical Drop are really “puzzles”. I believe the reason we call them puzzle games is because they feature abstract shapes and test processing and reasoning abilities in a very similar way to conventional puzzles, but they are distinctly games and not puzzles, because they are dynamic thanks to the use of Input RNG, and they have a variety of solutions, with a wide fault tolerance. You can make mistakes, leave holes, let junk pile up, and then rescue yourself with a variety of better/worse decisions. Your performance is measured, and there is a time pressure acting upon you. These factors make these very much games and not puzzles. Personally, I’m fine with a genre label being a misnomer, as long as we’re all clear about what family of works are being referred to when we use that label.

I do however think we should avoid riddles in many conventional games. A big component of fun is the joy of learning, of trying to find a solution to a non-trivial problem. Riddles run the risk of either being trivial when their signposting is very clear or being so obtuse that players need to consult a guide. It’s tricky for riddles to hit that sweet spot where players aren’t simply stuck or bored. Many players enjoy riddles and there is certainly a space for adventure games or conventional games with all kinds of hidden meta elements. But, this style of development, while easy to implement technically, has a very linear rate of return in playtime and can require a lot of man-hours to create art assets and custom scripts that will only be used once. Designers and Developers should be cautious about the costs and potential pitfalls of a riddle-heavy style of design.

Nuzzles are a form of riddle, and a game that is full of nuzzles is essentially full of light busywork. Many designers incorporate this as a way of giving players a forced rest between combat encounters or other intense sections of gameplay. I think that Nuzzles have a role as a tutorial mechanism, but I’m personally not a fan of the style of design that tries to force players to take a non-consensual breather. I think that this trend is a big reason why 3d Zelda declined in popularity over time, until BOTW did away with this practice and saw massive sales success.

That said, one of the better adventure games I’ve played recently is Night Manor from the UFO 50 collection. It has fairly clear signposting on nearly all of its “locks” and “keys” (environmental interaction points and items), so a lot of the challenge is simply remembering all the different interaction points you have seen in relation to all the items in your inventory.

In summary, riddles are about “Here’s a hint, now guess”. Puzzles are about “Here are some logical axioms, deduce the solution.” And games are about, “make choices and/or demonstrate your skills to get closer or further to winning.”

Hey, you *have* explored this topic, kinda 😛 https://critpoints.net/2016/12/03/puzzles-vs-games/

As a frequent puzzle game player I mildly disagree with the description of “games typically involve repetition and consistency” (consistency -> uncertainty?), because puzzles *are* more consistent than games. If a ‘puzzle game’ required uncertain execution elements I wouldn’t call that ‘more of a game’. I’d call it ‘less of a good puzzle’ and likely have a lower overall impression.

Being good at the types of consistent-mechanic puzzle games always involves a mental model of things you can do, and it’s not impossible to evoke an ‘uncertainty’ feeling from The Witness, like when you don’t know what a symbol means and must experiment (uncertainty!) to find out. This is an element that I thought was admittedly lacking in The Witness though.

I see a lot of riddles/puzzles in games that seem to be there to make the overworld feel more dynamic. Sometimes there is a ‘system’ but the puzzles are meant to be figured out by casual players and solved without a real roadblock.

(Oh, and when pruning puzzle search trees to look for potential ‘leads’ in puzzle solutions that “could” be called a tradeoff because you’re delaying looking at a branch, and humans sometimes put off potential successful leads. That’s probably beyond this article’s scope though and is not really what a ‘tradeoff’ as a typical choice in a game implies.)

LikeLike