Disclaimer: I know I’m dredging up a long dismissed argument from 10 years ago, and discussing it in all the same tone as people did back then, despite everyone having moved on. My core thesis is that the settlement to the argument was based on a miscommunication which solidified into apathy, without a real understanding of the form of the argument, and I think the topic deserves more consideration, because I believe games are art, but I also believe the people arguing that games were art ten years ago were right for the wrong reasons.

Over 10 years ago in the late 2000s, it was fiercely debated over whether or not games were art. Famous film critic Roger Ebert threw his hat into the ring by declaring that games are not art, and never will be art. Before he died in 2013, he half-heartedly recanted and admitted that some games were probably art, but more than anything, it feels like he kind of rolled over in response to a massive amount of backlash, rather than actually having a point made about what art is, and how games can fit that conceptual bucket. This seems to be the case, because a year before he died, he sent out this tweet:

The game that critic was talking about was DARK SOULS by the way. And you can read the article, it’s an incredibly uncharitable take on the game, but it’s also looking from the wrong perspective. Ebert, and everyone who argued against Ebert, were all looking from the wrong perspective. They weren’t arguing over whether or not games (interactive systems of play) were art, they were arguing over whether the software products we call games happened to have art packaged alongside the interactive systems of play. They were arguing over whether these interactive systems were art-adjacent, not whether they themselves were art. In other words, “Yeah, the game isn’t art, but look at all this art we included alongside it!”

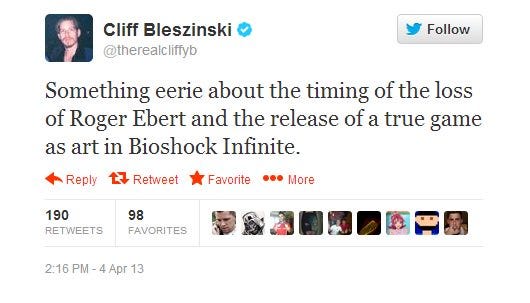

And this is recurring. What game did people try to tell Roger Ebert proved that video games were art? Shadow of the Colossus. There are plenty of other contemporary examples, like Bioshock, or Paper’s Please, or Cart Life, or so on. Cliff Bleszinski left us with this gauche statement in 2013 about Bioshock Infinite:

Why these games? Why not Mario 64? Why not Tetris? Why not Chess? Why not Soccer? It’s obvious, these games have stories and meaning. Bioshock centered on a city under the sea, built by an Ayn Randian objectivist, where capitalism could exist unfettered. Shadow of the Colossus had a beautiful art style and cinematic camera framing, along with a miyazaki-esque story about attempting to return the dead at the cost of your own soul, by attacking seemingly innocent giants. Paper’s Please modeled the way authoritarianism could override the humanity of common people. Cart Life… Lets be real, nobody remembers Cart Life, despite a bunch of games media praising it at the time. All of these stories are artistic. Most of these games had beautiful visual art directions that hold up a decade later, but it’s pretty clear that the reason people lean on examples like this is because it’s easy to compare them to cinema and literature.

And naturally, being a critic from another medium, Roger Ebert looked at the examples people tried to present him, and said they were facile and childish, which they were. They were nothing compared to what he was used to seeing in film. And if this was all there was of video games, then of course they’re barely art. If the stories of games are continually beholden to the cycle of success, failure, and retrying, then naturally they’re going to be pretty hamstrung narratively, because this isn’t a narrative structure. When people succeed or fail in a story, they move onto something else. If someone repeats the same thing twelve times, and eventually succeeds, you get a montage, not a retelling.

Apart from all of that, are we actually arguing that *Games* are art here? If this is what we resort to in order to prove games are art, weak and facile corporatized stories that regurgitate philosophy as set dressing, why are we not surprised when people with a serious appreciation for literature or cinema don’t take us seriously? *WE* don’t believe games are art, and we weren’t brave enough to tell Ebert that Tetris is art.

The gaming audience that cared about this topic is an audience of pop culture nerds. Fans of Science and Fantasy, not Huckleberry Finn. And this audience is insecure. 1 Corinthians 13:11 reads, “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” We Millenials (the generation of young adults shaping the conversations about video games at this time) were told that we could become anything we dreamed of. We were given permission to not grow up in this cynical self-serious way, to continue to enjoy the media we enjoyed as children. Not all of the world necessarily agreed with us. A lot of Baby Boomers and Gen Xers looked down on us for continuing to enjoy media originally intended for children, and this fostered nerdy insecurity, something which wasn’t new by the 2000s (Nerdy insecurity was also fostered by a lot of mainstream media, like movies and TV).

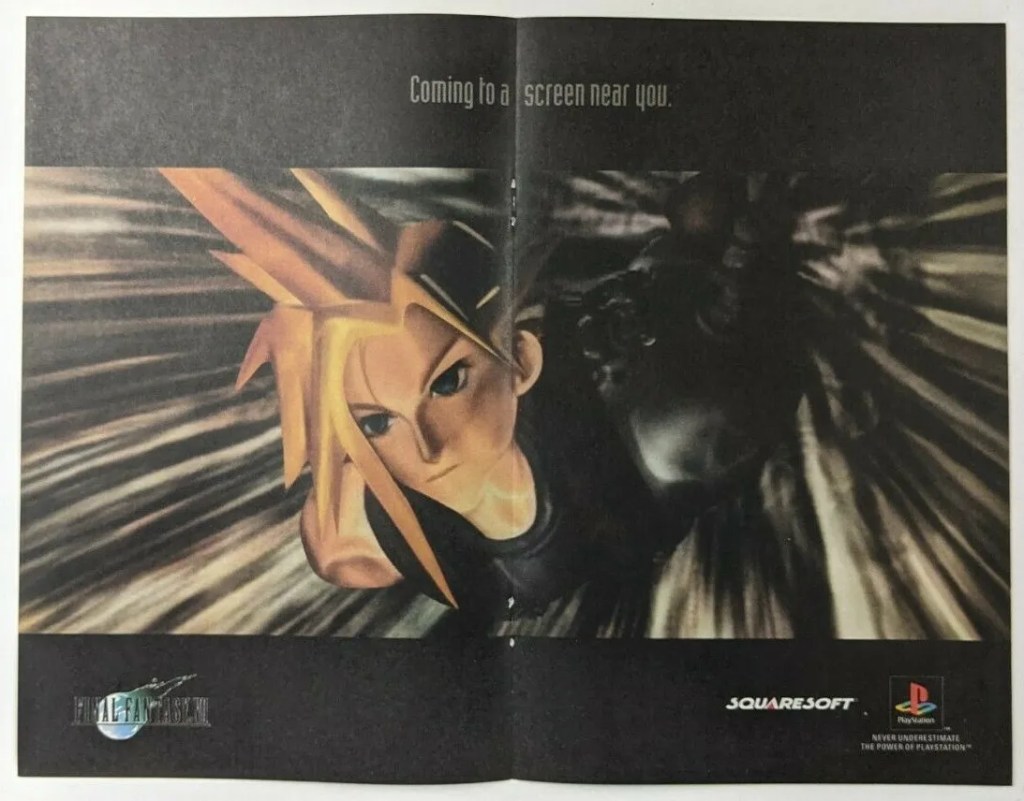

The story of the times was that the nerds had grown up, gotten corporate programming jobs, and taken over the world using the internet, iPhones, and personal computers. We saw games go from 8-bit pixels to intricate 3d renderings in the space of 2 short decades. Games during that time period began to compare themselves to films as they were able to present detailed pre-rendered, or in-engine cinematics. Final Fantasy VII had this print ad:

You can see that it’s evoking the line said in movie trailers. You can see the letterboxing applied to the image, intended to evoke the way films are letterboxes to preserve their aspect ratio, which evolved into a part of the language of cinema, where increased letterboxing indicates to the audience that a scene is meant to be taken more seriously. And that’s how you get this type of nerd peter pan syndrome, demanding to be taken seriously about this medium that finally “grew up”. Not secure in knowing that games are art, they demand that critics like Roger Ebert, one of the best known film critics of our times, take games seriously in the same breath as enduring works of literature and cinema. This is insecurity that demands prestige.

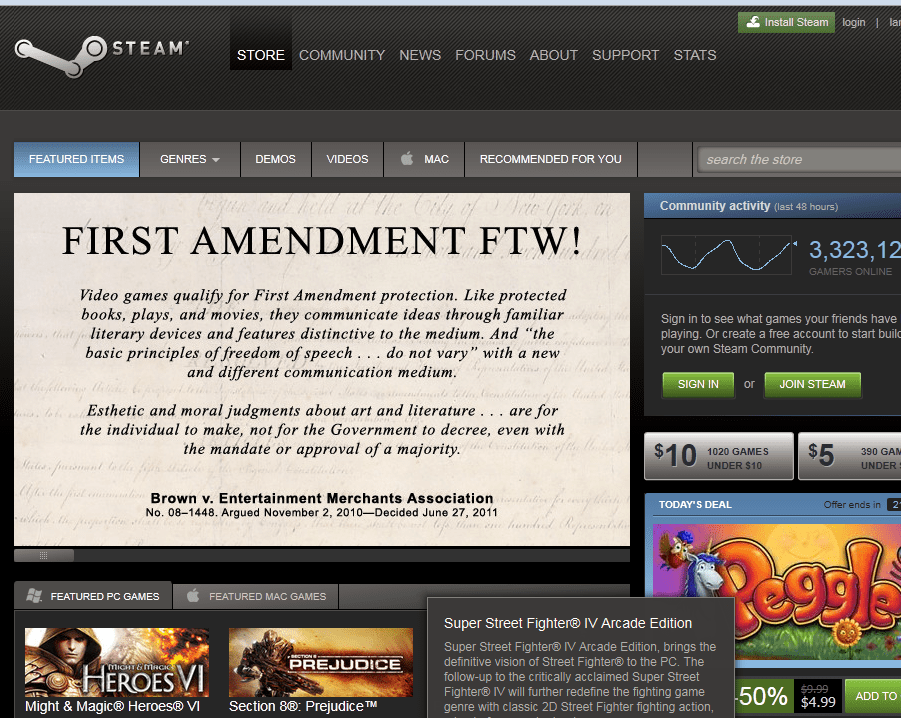

We saw this aping of cinema replicate itself in 2015 with The Order 1886 (5 years after Ebert’s article on how games will never be art), a game that touted itself as “filmic” and “cinematic” in its marketing, and went as far as to limit the aspect ratio for the entire game. Of course, this game has been utterly forgotten with time, because it was a 3rd person cover shooter that didn’t do much of anything to stand out from the deluge of other 3rd person cover shooters in its time. Games have had an envy of film that has manifested itself over and over again. Games try to prove themselves by copying an art form that they see as respected. When a first amendment ruling on the status of video games as free expression was made by the US Supreme Court, the Steam storefront displayed this on their front page:

This ruling was taken by many in the video game community to be an affirmative sign that video games were a form of art, and therefore were worthy of serious critical consideration.

Rather than say something sensible like, “art isn’t defined by merit,” or, “not all art has to have a message behind it, art can simply be,” nerds insisted that the most beautiful and meaningful games were in fact works of high literature, rather than just corporate art intended to profit from nerd cultural taste, in much the same way as a Marvel film. As if to say, “Of course *games* aren’t art, they’re just art-adjacent.”

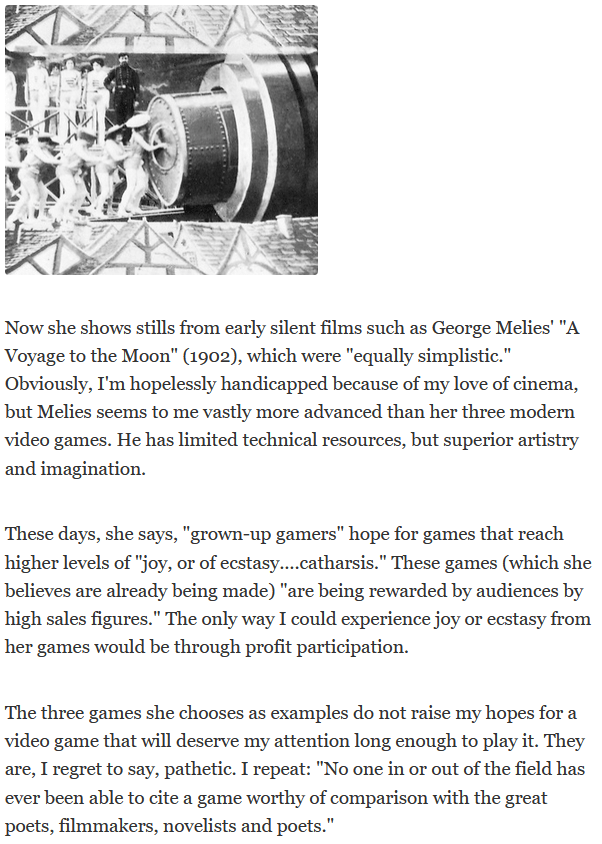

And we saw the rebuke of this attitude in Ebert’s article, Video Games can Never Be Art, which takes the form of an argument with a TED talk. The speaker of the TED talk, Kelee Santiago, “concedes that chess, football, baseball and even mah jong cannot be art, however elegant their rules.“

And the thing that fucking KILLS me is what Ebert writes in response:

“I agree. But of course that depends on the definition of art. She says the most articulate definition of art she’s found is the one in Wikipedia: “Art is the process of deliberately arranging elements in a way that appeals to the senses or emotions.” This is an intriguing definition, although as a chess player I might argue that my game fits the definition.“

Ebert was arguing with these nerds on a level they never matched. The insecure nerds, so righteous to prove themselves worthy, didn’t pay attention to Ebert’s own admission. Nobody wanted to engage him on his own terms, and try to expand his understanding of art. They simply wanted to be ratified in enjoying corporate nerd art. It was as if they were comic book fans trying to point Ebert to Watchmen, when they should have simply pointed to Garfield or Peanuts. It was an argument of categories, not merit, but the gamers weren’t seeking pedantic accuracy, they were seeking validation.

Why are gamers so intensely concerned, anyway, that games be defined as art? Bobby Fischer, Michael Jordan and Dick Butkus never said they thought their games were an art form. Nor did Shi Hua Chen, winner of the $500,000 World Series of Mah Jong in 2009. Why aren’t gamers content to play their games and simply enjoy themselves? They have my blessing, not that they care.

Do they require validation? In defending their gaming against parents, spouses, children, partners, co-workers or other critics, do they want to be able to look up from the screen and explain, “I’m studying a great form of art?” Then let them say it, if it makes them happy.

I allow Sangtiago the last word. Toward the end of her presentation, she shows a visual with six circles, which represent, I gather, the components now forming for her brave new world of video games as art. The circles are labeled: Development, Finance, Publishing, Marketing, Education, and Executive Management. I rest my case.

The rules of games are art. Soccer is art. The players are not artists, but the abstract concept of Soccer is artistic; All the strategies of Soccer, the rules of Soccer that create that possibility space. The person who made the rules of soccer was an artist, and people explore and interpret that art by playing the game of Soccer.

Now imagine playing a version of a video game without the art assets, where you just interact with the raw rules, the raw systems, the raw spaces. You only see the grayboxes of levels, rather than the final meshes. Imagine how that is artistic in its own way. Maybe it’s not as appealing overall, and maybe it suffers a bit for not giving as clear or understandable feedback (visual design and sound design impact the game design too!), but try thinking about how this too is a type of art.

We’re never going to break free of this until we can stop thinking of art in a purely representational, purely message-driven way and we keep repeating this discussion all the time because the lesson isn’t being learned, it’s just being handwaved. Without an adequate conception of art, or the place of games in art, we can’t resolve this lingering cognitive dissonance, forcing us to dodge the question whenever it comes up, or take it for granted. People took this issue seriously a decade ago, but the arguments were based on a miscommunication. This miscommunication persisted so long that people eventually got tired of it and decided the whole thing was settled and that the argument was actually kind of pointless rather than actually interrogating the ideas involved. This is why most articles or video essays discussing this topic just go, “no duh, it’s art,” instead of taking the question more seriously, or insisting that games are full of these incredible works of literature and cinema.

Even a lot of responses to this article have dodged the actual question, going, “Of course games are art, Disco Elysium proves it!” Again, showing that the commenter doesn’t think games are art, but that Disco Elysium is a great work of literature, which they safely know is art, instead of having to grapple with the idea that tic tac toe or hopscotch might be art. I fully agree that Disco Elysium is an incredible work of literature, which is artistic, but that is still an argument that games are art adjacent, not art inherent.

I believe games are art, I’d like everyone else to start believing it too.

I’m glad I came across this blog by chance. The point you conclude with is one I’ve been failing to articulate for literal years. There’s that sting whenever I see someone try to answer the question of whether games are art with “of course they’re art! look at this one video game!”.

If your argument is to point towards one specific work, does that mean it’s an exception, and most other games just aren’t art? So this status as art isn’t intrinsic to the medium, then? Then are games, plural, truly art?

Chess is art too, and not because the pawns have a funny shape. That’s what I’ll say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Games are art-inherent, not art-adjacent. Glad you enjoyed it! I’ve been beating this drum for years, and some people commenting on this article on other websites even said things like, “Disco Elysium proves that games are art,” completely missing the point.

LikeLike

I appreciate what you’re trying to say here, but I feel you’re leaning far too much into a certain direction. You’re text comes off even horrendously elitist at times, as in the “regurgitate philosphy” section. I don’t see many heralded works of literature or film moving too much beyond it. Sure something like Brothers Karamazov very painstakingly interacts with hardcore philosophical problems. But celebrated audivisual works like Fight Club or Twin Peaks are relatively ephemeral.

You mentioned Papers Please in your article, but doesn’t it do an exceptional job of viewing the narrative together with the game system? In interracting with the rules of the game, you are led to make narrative choices. On a much lesser level, the original Bioshock also comments on its own necessarily linear structure, and yet again interacting with the game system is intervowen into interacting with the narrative.

Yes the game system in themselves are art, but they’re not the type of art most people are clammoring to interact. Academic formalists, seeking detached aesthetic pleasure might very well induct games as objects of research and into their canons. But art that the common person wants to interact with intertwines aesthetic stimulus with emotional sensations. The art that makes people feel necessarily incorporates aesthetics and narratives.

LikeLike

I totally agree with you. Also when breaking down a video game to its core, it must involve some sort of pixel composition on the screen – not simply its rule system or coding, as the author seems to imply. I would argue that the visual component is essential for video games and that it is one of the main aspects that makes a game artistic.

LikeLike