I have a 4 factor model for move/option design in PvP games:

- Stake (how much you stand to lose by choosing this option, either in costs or penalties)

- Reward (how much you stand to gain if this option succeeds and stand to gain regardless)

- Difficulty/Chance (the likelihood that the option will be successfully executed)

- Counterplay (what range of options this move beats, and how hard/soft a counter)

The purpose of dividing across these 4 factors is to help illustrate to designers the different levers they can pull, instead of focusing purely on a linear risk/reward relationship.

It’s common for a lot of designers to get stuck thinking that everything risky has to have a proportionate amount of reward, and everything rewarding has to have a proportionate amount at stake. Having lopsided stake/reward relationships is possible and healthy when the difficulty and counterplay are considered.

A subtle factor of this model is that cost is a type of risk, and therefore something you put at Stake. When you pay a cost, you’re risking that that investment won’t pay off. Therefore An upside of this model is that it separates Risk from Difficulty/Chance of Success, which are often conflated. “This move is risky, because you’re likely to mess it up.” By separating Risk out into Stake, Difficulty, and Counterplay, we can think more carefully about how each of these different factors play into an option’s design, and we have a wider design space for option design.

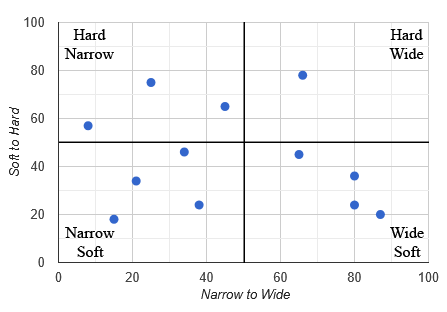

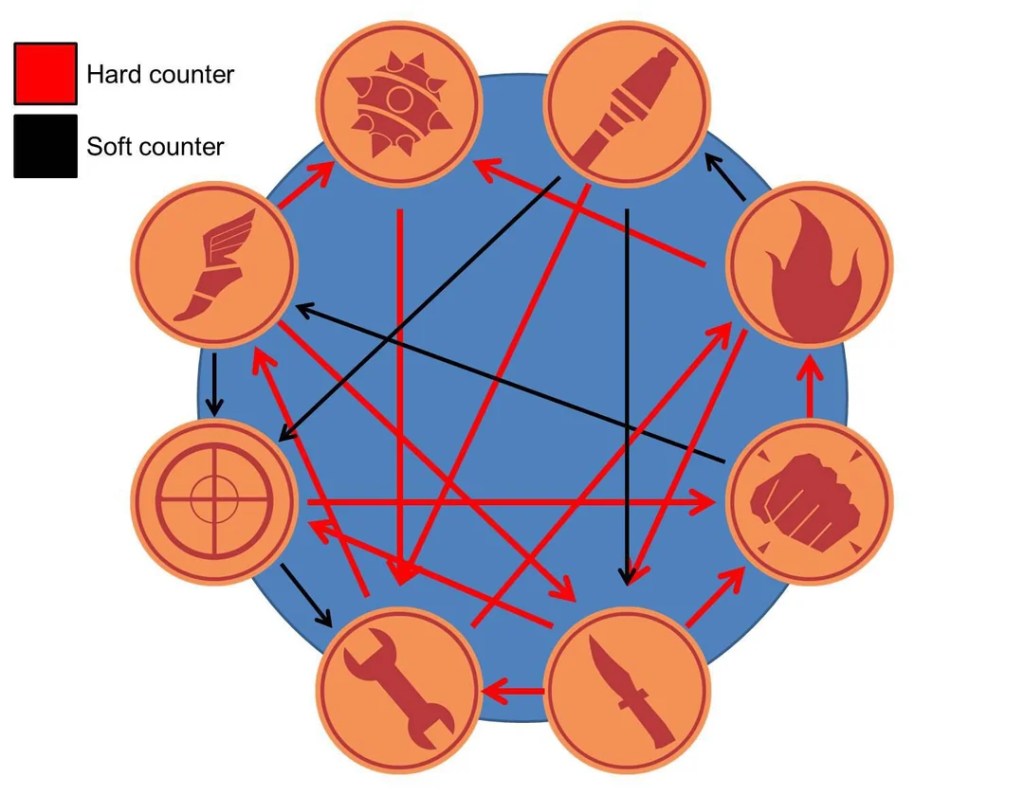

Within counterplay there is a lot of nuance to how counters can be designed. I’m going to identify 2 spectrums:

- Hard vs Soft

- Wide vs Narrow

A hard counter is one that is guaranteed to always shut down the option that it counters. A soft counter is one with more wiggle room.

A wide counter can beat a wide variety of options. And a narrow counter can only deal with a very specific one.

By dividing counterplay across these two axes, we can see the relative strengths and weaknesses of different moves and intentionally alter the counterplay of moves relative to our needs.

Magic the Gathering

I think that Blue Counter Spells are fairly illustrative of how counterplay works in broad strokes. Blue is the only color with consistent access to counterspells. A counter spell will stop an opponent’s spell before it resolves, but counter spells are limited by what range of spells they can counter (it’s usually easier to counter non-creature spells). Counter spells also cost more or less mana relative to how hard and how wide a counter they are. In other words: You are putting more resources at stake in order to get wider and harder counterplay

The original Counterspell cost 2 mana. It could hard counter any spell, making it very powerful. It was later decided that having this wide and hard counter was too strong, and only 3 mana counterspells would be printed (This usually made them slightly too expensive to be worth it, so they have been stapling upsides onto 3 mana counterspells ever since). So, the going rate for a hard and wide counter is 3 mana.

For 2 mana, we can see that counterspells start getting more specific about what they can deal with, or start becoming soft counters instead of hard counters. Negate and Essence Scatter are both hard counters, but negate is very wide, and essence scatter is very narrow. Mana Leak is a very wide counter, but it’s a little softer than Cancel. It lets the opponent choose whether or not to pay to let the spell resolve, which means it can’t always counter everything.

For one mana, the tradeoffs get even more steep. Spell Pierce is a soft counter of any non-creature spell for 2, meaning it’s very wide, but very soft. Miscast can only counter instants or sorceries, but the opponent has to pay 3, which is a harder counter. And Dispel will hard counter an instant, no questions, making it a very hard and very narrow counter.

Hopefully this makes it clear how counters can be designed to be more hard and narrow, more wide and soft, or more costly to allow for both. It’s also worth mentioning that Blue as a color has a weakness: Blue isn’t very good at getting rid of cards that have made it successfully onto the board.

Black is another color with a very similar set of tradeoffs for removal.

To unconditionally kill a creature, you need to pay 3 mana. To do this for less mana, there is usually a downside, like paying life, or sacrificing a creature, or discarding a card. Most recently, a card was printed that could unconditionally kill a creature for 2 mana, but it was limited to sorcery speed (your turn only, when nothing is currently happening).

At 2 mana, black has all of these very wide sets of removal. They can kill everything, except [blank].

For 1 mana, kill spells tend to focus on weaker creatures, or have more serious downsides.

You might notice that these appear to be very hard counters, and for the most part, they are, except that every color has a way of dealing with them. Blue can outright counterspell them, but other colors can protect their creatures in various ways.

Because each color can interact, it helps make black’s kill spells somewhat softer counters. For the ones that check the creature’s power and toughness, a simple buff spell will protect the creature. This is also true against Red’s damage spells.

Yu-Gi-Oh

Yugioh has a similar relationship with its interaction, except Yugioh counterplay is very hard and precise, because Yugioh cards don’t really have costs per-se, which it would need in order to have softer counters.

These four hand traps are probably the most fundamental units of interaction in Yugioh. Ash Blossom can negate any effect that would search the deck or draw cards. Effect Veiler can negate any monster on the field. Ghost Belle can prevent cards from leaving the graveyard. And Ghost Ogre can blow up a monster activating its effect.

Each of these is a different type of counterplay, with its own narrow band of effectiveness and payoff. Ash Blossom, Effect Veiler, and Ghost Belle all negate the effect, but Ghost Ogre will destroy the monster without negating it. This, interestingly, makes it a bit weaker than Ash Blossom or Effect Veiler. Ghost Ogre can deprive the opponent of resources they need to combo, but it can just as easily let important effects go off without a hitch. The monster is also sent to the graveyard, which many Yugioh players refer to as “The Second Hand”, meaning it’s very likely to come back. Ghost Ogre can be argued to be a softer counter, insofar as Yugioh has soft counters. Effect Veiler can also be viewed as a soft counter, because it leaves the monster behind as ammunition for the opponent’s future plays.

Because Yugioh mostly lacks the resource systems of other card games, it has difficulty creating softer counters, frequently needing to make counters more narrow in scope in order to balance them.

PSY-Framegear Gamma is a harder counter in the same vein as Effect Veiler and Ghost Ogre. PSY-Framegear Gamma will both negate and destroy an opponent’s monster when it activates an effect. It’s also a slightly wider counter, because it doesn’t depend on the opponent’s monster being on the field. The “cost” to this is that you need to stick a PSY-Frame Driver into your deck; a dead card if you draw it.

The widest counters in the game include Solemn Judgment, Solemn Strike, and Baronne De Fleur. Solemn Judgment can negate and destroy any summon, spell, or trap card. Solemn Strike can negate and destroy any special summon or any monster effect. And Baronne De Fleur can negate and destroy any card activating an effect at all. Between the three of these, there are very few holes. The weakness of the first two is that they are trap cards, and are therefore too slow to see much play in the modern game. The weakness of the last one is that it can’t stop summons, not that that’s much of a weakness!

Yugioh is a tricky game to analyze through this lens. Although it’s easy to point out how counters are wider or more narrow, Yugioh has almost no standardized card templating of any kind. All of the interactions in Yugioh are somewhat mismatched, situational, and have vastly different costs and payoffs. This is also part of what makes it such an interesting game.

Fighting Games

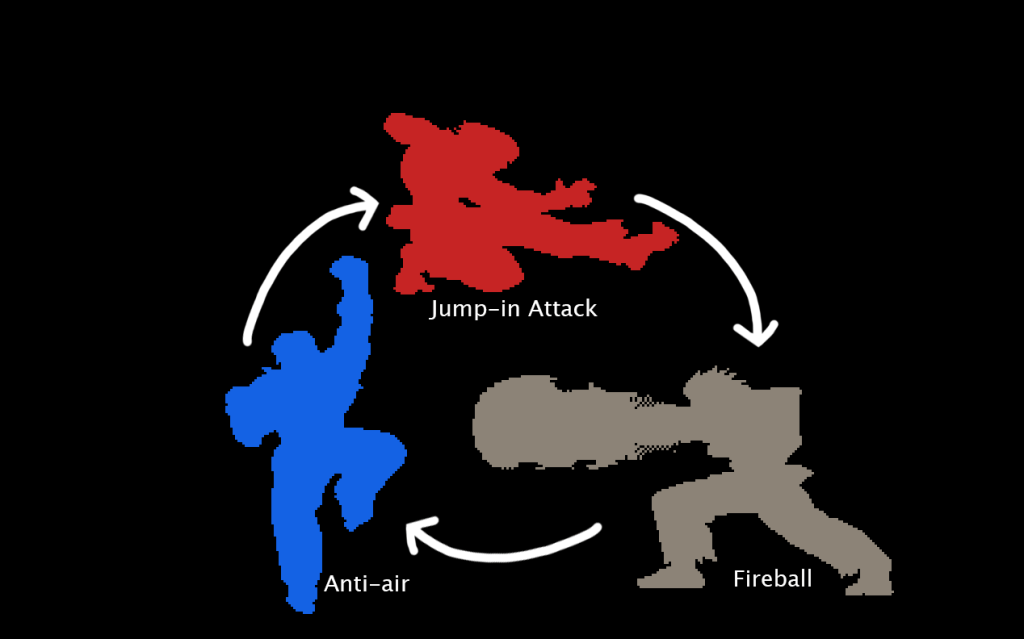

Everyone talks about how Fighting Games are big games of Rock Paper Scissors, so this is kind of old hat.

I’ve made a video explaining a lot of these rules in more generalized terms. What’s important is, fighting games tend to have fairly soft RPS. You can win with just one button if you never press it at the wrong time. Distance and Time act as modulators for the RPS of fighting games, so different moves are more likely to win at different distances, and moves can win or lose depending on how fast they are, or what time they’re used.

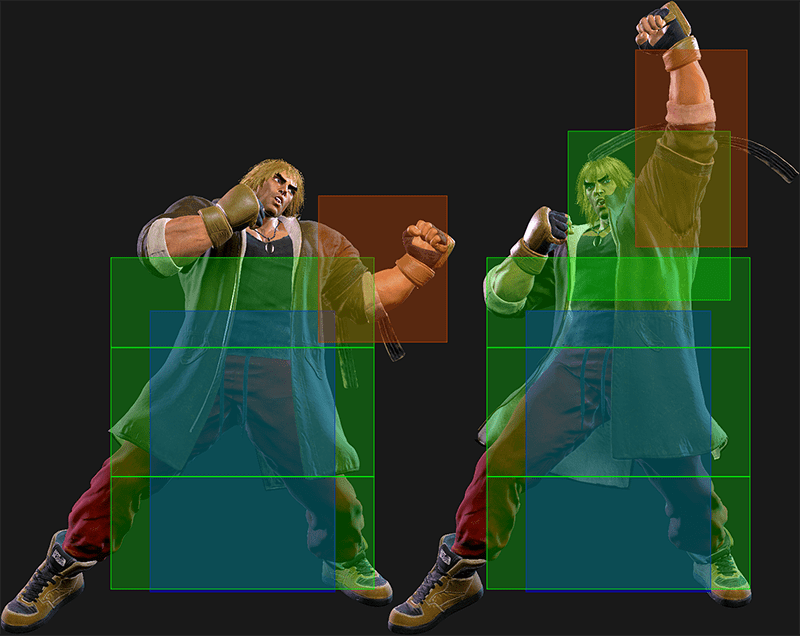

Some fighting games design their system to make the RPS more soft, and others more hard. You can achieve harder counterplay by using properties, like making a move invincible to air moves, invincible to low or high attacks, or invincible to throws. These properties can make it more clear how a move is supposed to be used, or more rigidly enforce which moves it’s supposed to beat. I believe that having a good mix of hard and soft counterplay makes for an interesting game.

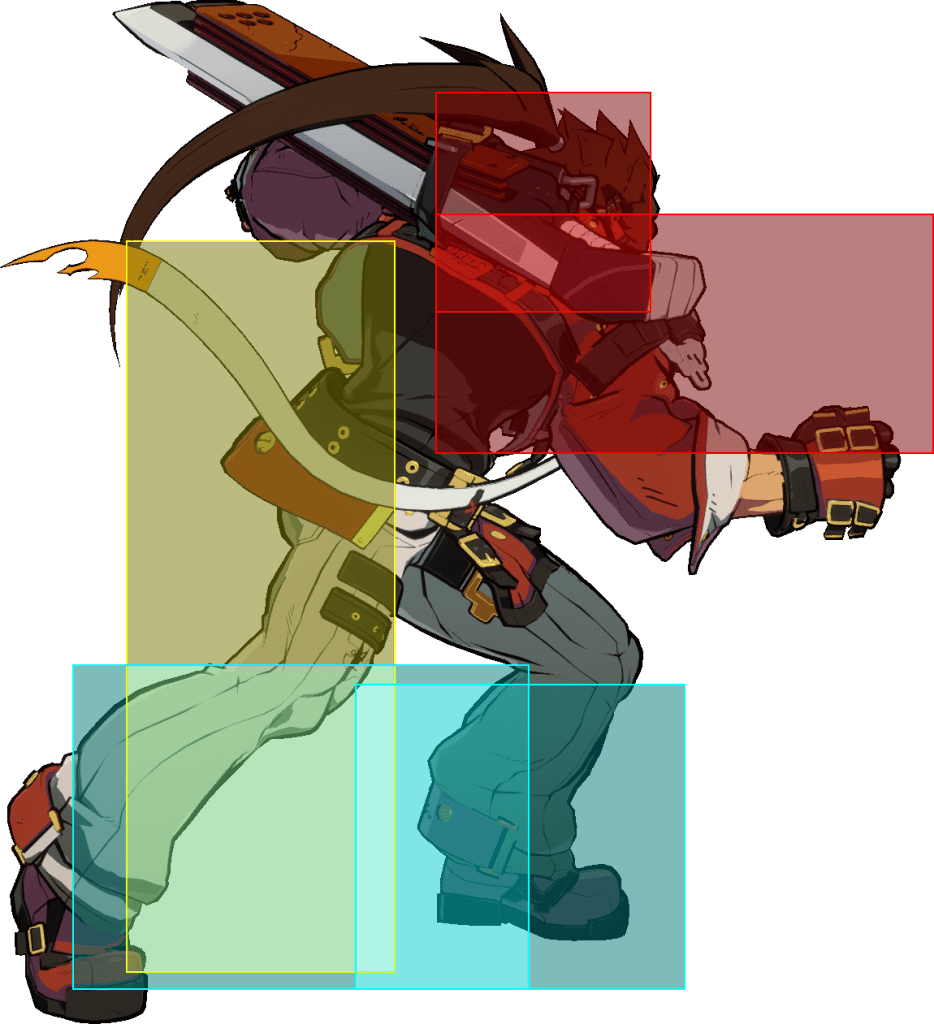

Guilty Gear chooses to give 6P (forward + punch) upper body invincibility. This makes it a softer counter against airborne attacks, since you need to time it more carefully to avoid getting hit, and attacks with different hitboxes can hit you anyway. It also makes 6P a wider counter, since it can evade many poking moves in neutral.

Blazblue, Under Night, and Dragon Ball FighterZ chose to give their anti-air normal attacks the “Head” invincibility property, making them immune to airborne melee attacks. This means they will always cleanly and consistently beat airborne attacks, making them a harder counter, but not allowing them to beat poking moves on the ground.

Street Fighter 6, interestingly, decided to combine both of these approaches by marking the upper body hurtboxes of the character performing the anti-air move invincible to air attacks. This means that they’re a somewhat soft counter against jump-ins, but also that they cannot be used in neutral to beat poking attacks, making a more narrow soft counter, instead of choosing between a wide soft counter and a narrow hard counter. Notably, this does mean that anti-air moves in SF6 are a harder counter to jump-in attacks than they were in prior games. This is a subtle touch to add consistency to an interaction that wasn’t very consistent in Street Fighter 5.

Counterplay between characters can also be messed with by looking at the ranges of each characters’ attacks, and how fast they come out. Merkava is an interesting character in Under Night, because none of his attacks are best-in-class, but one of them is always better than the character he’s fighting. Merkava isn’t the best zoner in the game, but he has attacks with longer range than any of the rushdown characters. Merkava doesn’t have the fastest rushdown in the game, but he has faster attacks than all the zoners. Merkava figures out a character’s best range, and tries to be in the range that character hates.

Leo Whitefang has a similar playbook. In his backturned stance, he loses the ability to block or throw, but gains faster attacks than the rest of the cast, forcing them to play a guessing game that is heavily lopsided in his favor. In this mode, he has faster attacks for each range (punch, kick, and slash ranges) than anyone else has, and he can mix in fast throw-invincible lows and overheads to open opponents up. Leo can cheese some opponents at the edge of his slash range by just having a faster slash attack for that range than they do.

These moveset designs give these characters harder counterplay when attacking at these ranges.

For width of counterplay, we can look at invincibility and super armor. Super Armor helps moves beat enemy attacks, but it typically is limited to absorb only a certain number of hits, and lose to throws. This can make armored moves wider counters, since they now beat faster strikes. Adjusting the number of hits they can absorb can help tune armored moves to be softer or harder as a counter. Some games allow moves to break armor outright, also affecting how wide a counter they are.

Invincibility can be deployed in a similar way. The Dragon Punch is the classic example of a move with very wide counterplay. If you can always dragon punch right when your opponent does something, you can’t lose. The downside is, if your opponent blocks or does nothing, then you’ll eat a punish combo. Moves can also be given specific types of invincibility, between strike, throw, and projectile, in order to affect how wide of a counter they are. As discussed earlier, some games even assign invincibility against air, high, or low moves. Projectile invincible moves can sneak through an opponent’s zoning. Strike invincible moves can lose to throws, same as armor. Throw invincible moves can help you escape a pressure situation, or call out an opponent’s throw tech.

Street Fighter 6 decided that level 1 supers were throw and strike invincible, but not invincible to projectiles, meaning projectiles can help safely chip an opponent when they’re down if they only have level 1 available.

Street Fighter has gone through an evolution in how it treats counterplay from SF4 to SF6.

SF4 had the issue that option selects created very wide counters that could beat practically any response (and they were fairly opaque to understand without being taught the OS). This lead SFV’s designers to force players to commit more to their options. This also meant that they removed a lot of options that had wide counterplay, but lower rewards.

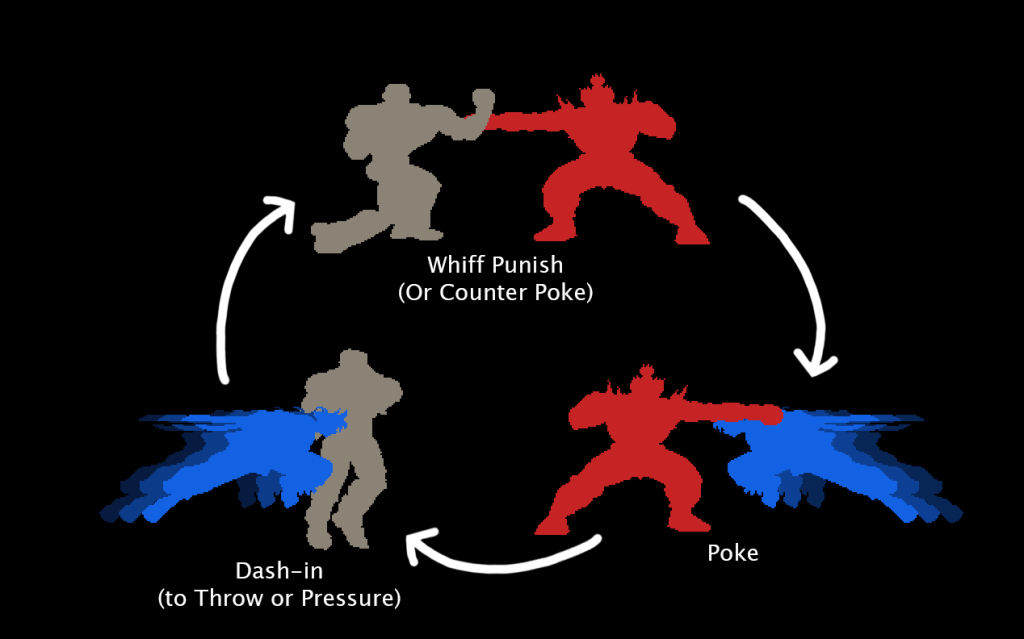

This design direction ended up narrowing the range of options for pressure and knockdown situations. The game converged on 3 options: Strike, Throw, and Shimmy (stepping backwards to bait a throw tech and punish); with the responses: Block, Tech, and Low Attack. Do you block the strike, do you tech the throw, or do you low attack the shimmy? If you had meter, you could EX Dragon Punch your way out (because meterless dragon punches weren’t invincible anymore), but otherwise you had to eat the mixup.

Street Fighter 6 dialed back from the forced commitment angle a bit, and added some powerful new defensive tools to try to mitigate the mix a bit. Drive Parry let you block both high and low, and you could parry strikes with perfect timing to counter attack. Drive Impact was a new move with 2 hits of armor, letting you armor through an opponent’s strike. Unfortunately, these options didn’t change the fundamental mixup, because both of them lost to throw, rather than creating a more complex RPS chart, or getting more options involved (and Drive Impact also lost to strike with good reaction time).

The way that other games solve this is by giving players some invincibility to throws when they wake up from a knockdown. This means that rather than needing to tech a throw, a wakeup attack can beat the throw outright, meaning throw only works as a meaty option if the player has been conditioned to block. This helps make the counter to meaty throw a less wide option and it can help make the counterplay softer too.

I’m not trying to suggest here that softer counterplay is inherently better. A game with very soft counterplay can end up like a weird mush where nothing really beats anything. A game with very hard counterplay doesn’t care a lot about situational factors and boils down to simply which option you select. Depth is created through differentiation, and that includes differentiating between harder and softer counters.

High and low blocking is a way that fighting games make blocking less of a hard counter to attacking (drive parry blocks both high and low, making it a harder counter). Some attacks hit high and low, requiring the defender to pay attention and react to attacks in order to keep their defense up. Under Night makes throws softer counterplay by giving them a wide throw tech window of 14 frames. If you’re thrown during hitstun or blockstun, that window doubles to 28, but if you were shielding, you don’t get a chance to tech at all. This helps make defense in Under Night more about soft counters, rather than hard counters. The attacker can’t force the defender to eat a tough mixup, so the defender can deploy a more variable defense. Helpfully, characters are also allowed to have meterless reversals in this game and every character has access to a reversal of some type, in addition to an alpha counter, and an invincible forward roll.

UFO 50: Hyper Contender

UFO 50 has a fighting game in it, surprisingly! It’s called Hyper Contender, and it’s a platform fighter. It only has 3 options, Projectile (X or Up + X), Melee (Down + X), and Block (hold down). Despite this simplicity, it manages to create a counter triangle that actually works really well!

In Hyper Contender, you win by collecting 5 rings, which periodically spawn every 15 seconds. You can hit your opponent to get them to drop rings they’ve collected. Your primary means of attack is by throwing projectiles. These projectiles can’t be blocked, but melee attacks will dodge them. If you block a melee attack, your opponent will be stunned, and hitting them will cause them to drop 2 rings.

This means there’s a triangle of: Projectile < Melee < Block < Projectile.

Hyper Contender then has softer counters in the form of some projectiles destroying others, and the shape and path of different attacks and forms of movement, allowing for options to win or lose based on your timing and spacing.

Despite being so simple, Hyper Contender shows that an understanding of the fundamentals can make a solid game, even under extreme limitations.

Team Fortress 2

TF2 has a variety of different classes that each have unique strengths and weaknesses. Which classes counter which has been a topic of debate since the game came out, and the balance of the game has never been the greatest (Medic and Demoman are far more powerful than the other classes; Sniper, Spy, and Pyro aren’t fantastic).

Some of the classes have a counter relationship with one another. Engineers can deny space with their turrets. Spies can cloak and disguise themselves to sneak into the Engineer’s turret nest, and then use their sapper to disable and destroy the turret. Spies can also sneak up on snipers to backstab them. Pyros can set spies on fire, revealing their cloaking or disguise. This is about as hard as counterplay gets in TF2.

What makes counterplay generally softer in FPS games is that there is no hitstun. If a player is hit by a shot from their opponent, they don’t lose any capability to fire back. This means both players are likely to take damage in any given encounter. Therefore, class matchup counterplay is more about damage per second (DPS), and the counterplay of FPS games in general is more about who fires the first shot, at what distance, with what teammates, and in what terrain. In other words, you counter your opponent by choosing to engage when you have the upper hand, and avoiding engagement when you don’t.

The Pyro has higher DPS than Scout’s scattergun at close range with its flamethrower, and it has higher damage than Scout’s pistol at long range with its shotgun. The Scout has the overall advantage in the matchup though, because it’s faster, and can therefore dictate the terms of engagement, zooming out to force the Pyro to switch to its lower DPS shotgun, then zooming in to out-damage the Pyro’s shotgun with Scout’s Scattergun. The big disparity is that the flamethrower’s DPS is high up close, but nothing at a range, so Pyro is forced to switch or lose, whereas scout can always get some damage, even if it isn’t optimal.

In this way, FPS games can have a very similar counterplay paradigm to fighting games: Who has the more effective weapon at a given range? Of course, in the landscape of low time to kill (TTK) FPS games, this becomes less important than who fires first, so victory is less about getting the opponent into your effective range while staying out of theirs, and more about ambushing your opponent.

Starcraft Brood War

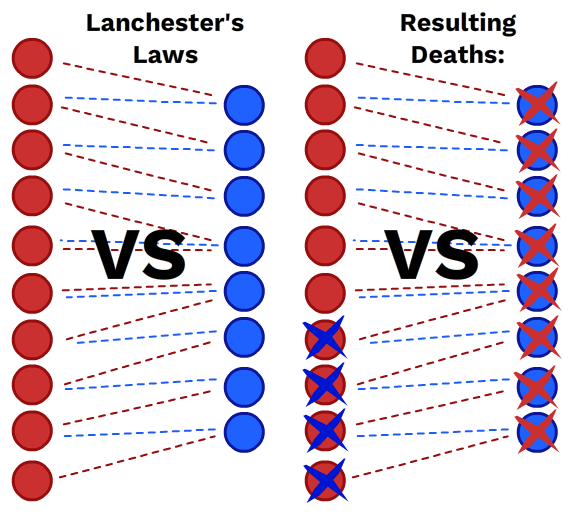

Starcraft Brood War is a game with mostly soft counters, and a few hard counters. In general, strategy in Starcraft is about having more units than your opponent does, and more expensive units. Starcraft is a big money fight. You want to mine more minerals, spend more of those on units and buildings, and destroy your opponent’s investments or deny your opponent from doing the same.

In general, the big rule is, attack with more units, and flee when you have less units. This is down-stream of Lanchester’s Laws, which basically say that a group of combatants grow exponentially stronger the more units you have and will survive with dramatically more remaining troops than the difference in size between the forces. So the big RPS of the game is picking good fights and avoiding bad ones. The terrain, unit selection limit, and derpy unit AI make it so you can’t ever concentrate all your units in one place or get them all fighting at max efficiency, so players always have something to exploit in their opponents.

The hardest that counters get in Brood War is Air vs Ground, and Cloaking vs Detectors.

Each unit is either an air unit or a ground unit, and each unit’s weapons can hit either ground, air, or both. If a unit is attacked by another that is in the space it can’t shoot at, it’s a sitting duck. For example, Siege Tanks can’t hit air units, so they get torn apart by Mutalisks. And Corsairs can’t attack ground units, so they can be torn apart by Hydralisks.

Some units can cloak themselves, like Wraiths or Ghosts for Terran. Any Zerg unit can burrow, but Lurkers can attack while burrowed. And Protoss has the Dark Templar and Observers, which are permanently cloaked. If a player doesn’t have detector units, their units can’t see these units at all, and can’t hit them. Terran can detect cloaked enemies with the Comsat Station, allowing them to scan an area; Missile Turrets, which have detection around their range; and with Science Vessels, which can float above enemies and function as detection. Protoss is limited to only Observers and Photon Cannons, functioning much like the Science Vessel and Missile Turret. And Zerg has detection on their observers, which are slow flying units that Zerg uses for supply and for air lifting units.

Choosing to build for cloaked units and to get detection can be an RPS choice in a match. Protoss is weakest against detection, since they need to purposefully build to Observers to get good detection. Terran can get a comsat station online fairly early, and it’s common to do so for basic scouting. Zerg has Observers from the start, and they’re practically omnipresent across the map, making detection fairly simple for them.

On the softer side, some units do counter other units. Protoss Corsairs are a great counter for Mutalisks, because Mutalisks tend to travel in balled up formations, and the Corsair’s weapon deals Area of Effect damage, melting the whole Muta Stack at once. The Science Vessel can also screw up a stack of Mutalisks by irradiating one of them, poisoning the whole stack at once, and being really difficult to manually separate out of the stack.

An incredibly strong soft counter on the ground is Siege Tanks versus practically any other ground unit. Siege tanks, when switched into Siege Mode, become immobile and fire high damage shots incredibly far, but they have a minimum range, meaning they can’t attack units that are right in their face. This means they counter enemies further out from them, but they get countered by anything that can get up in their face. This makes the placement of Siege Tanks, so that they can cover each other, incredibly important. Of course, if a Siege Tank fires on an enemy in front of another Siege Tank, it will hurt their ally too, but that’s usually better than losing your whole formation just because an enemy unit got air dropped in.

Tight formations of Marines are effective for fighting Zerglings, because Marines will grow exponentially stronger as they have more units, but Zerglings will only grow linearly more powerful the more zerglings there are. By balling up tight, Marines expose less surface area, preventing Zerglings from hitting them all at once.

For contrast, wide formations of Marines are better for fighting Mutalisks, because Mutas have a projectile that bounces from unit to unit, and a spread formation limits the number of bounces that can be taken.

In these ways, the way you move your units can help them more effectively counter different enemy units. In a more generalist way, there are other micro tactics that can be employed to counter your opponent’s units (in an RTS context, micro means controlling your armies, macro means producing units and buildings). You can order your ranged units to all focus-fire on enemy units, especially if they’re weakened, reducing your opponent’s fighting power. And you can pull injured units off the front line, causing the enemies to disengage, preserving your group’s damage potential for longer.

In this way, choosing to devote your focus to a battle increases the fighting efficiency of your units. In some cases, this can vastly increase the damage output and survivability of units. Where you choose to allocate your units and devote your focus versus where your opponent chooses to do so is therefore a big part of the RPS of the game.

In even more broad strokes, there’s an element of RPS and counterplay in your Build Order (the order in which you build; your early game strategy). It follows a counter triangle of Rush < Turtle < Greedy < Rush. This is a pattern that exists in many more economic PVP games, which some people call The Strategy Circle. Rush aims to win the game quickly. Turtle aims to stop an early win. Greedy, or Economic, aims to accrue resources to overwhelm a defensive player. Rushing can cripple an undefended opponent, making it impossible for them to mount a comeback. A good strategy will mix these approaches and adapt to the opponent’s strategy.

In Brood War, a rush typically means skipping on scouting in order to focus all your workers and money on pumping out offensive units as fast as possible, then firing off a critical mass of units at your opponent’s base. Turtle means walling off your base and using chokepoints and the defender’s advantage to fend off the rush, coming out ahead because you maintained economic production and can expand sooner. Greedy means expanding immediately, boosting your income, but having nothing to defend yourself. Conventionally, players will play a mix of defense and greedy, walling off their easily defended natural expansion. It’s not as good at defending against a rush as walling off their starting base, which usually has a tighter choke point, but it’s usually more than good enough, and worth the risk.

In other RTS games, units typically have harder counters than in Brood War. Soft counters can still exist in a game of hard counters, because players can mix and match different units into the same squad, allowing different mixes and concentrations of units to perform effectively. We can see this in Brood War as well in some cases. Corsairs hard counter air units, and Dark Templars are cloaked, hard countering armies without detection. This means that versus Zerg, Corsairs can kill the overlords in the air, leaving the Dark Templars free to kill the ground units. Zerg can counter this by focusing on Hydralisks, which can hit ground and air units at a range. From there, the counterplay comes down to who manages their army better, and engages on better terms.

Action Puzzle Games

In many action puzzle games, you can break blocks to send junk blocks to your opponent. Both players can see each other’s screens, so there is a lot of public information, but neither player can predict the other’s intentions in the moment. That means that there are 2 big variables in how you interact with your opponent: When you send blocks and how many blocks you send. This means that RPS in Action Puzzle games is extremely simple, it’s just a form of the Shell Game.

The Shell Game is a game where one player hides a ball under a shell (or cup) and the other player has to guess which shell it’s hidden under. The Shell Game is technically supposed to be a fair contest of skill for the choosing player, their ability to watch the shells get shuffled, but for our purposes, we’ll just say that the ball is hidden under a cup chosen by the hider. In other words, there is hidden information, and disproportionate outcomes based on that hidden information, making it another way of formulating rock paper scissors. There can be 2 shells, 3 shells, 4 shells, or more, and the payoffs for each shell can be distributed differently too (as seen in Guilty Gear Faust’s super that is literally the shell game, with a variety of different damage payoffs).

So, players of action puzzle games can choose to send junk blocks sooner or later, and to send more or less. Maybe they want to send a few blocks right now to block the opponent’s attempt to score, or maybe they want to send an overwhelming number of blocks to win outright, or maybe they’re sending blocks to neutralize the blocks being sent at them, in order to survive. These different actions will have disproportionate impacts based on when the blocks are sent over, and how many. Future Action Puzzle Games could maybe investigate giving players more control over where the junk blocks are placed on the opponents’ screen, or what type of blocks they are, in order to add more counterplay to the genre.

Racing Games

Racing Games are fairly similar to Action Puzzle games, in that they’re mostly about testing the players’ skills, rather than directly interacting. Racing games, apart from Kart Racers with powerups, typically also have a form of the shell game when the players get close together and try to pass one another.

To simplify racing games a lot (I don’t really play racing games, sorry), you can go right or go left, leaving the other option open to your opponent. If you both guess the same side, the player that’s behind will stay behind. If you guess differently, the player that’s behind has a chance to pass, assuming they can take that path faster than the car ahead of them.

Racing games can also limit these types of plays, such as by inflicting damage onto the car, or demanding another resource. In real life, a Nascar Racer, Ross Chastain, pulled a move like this in the final lap to pass other racers for the win.

Conclusion

If your game allows players to interact with each other directly, to affect one another, there will always be counterplay, and there will always be some element of Rock Paper Scissors, a Non-Transitive Relationship. Since this is inevitable for direct interaction PVP games, it’s worth understanding how this works, what type of interaction you’re creating, and how to make it as interesting as possible, so that you can know what you’re doing, and decide if you want direct interaction at all.

I think this article needs more images of Brood War and Street Fighter, but I don’t have time to set those up right now, so I’ll probably come back to it later.

LikeLike

Alright, I think the images are mostly good now. Could maybe use a couple more for Brood War, but that’s tricky to set up.

LikeLike