A bunch of different videos have popped up lately in fighting game circles, about “Emergent Gameplay”. I’ve watched a number of them and they’re grasping at concepts they can’t totally describe. They use a lot of vague terminology and almost say what they want to, but not quite. The gist is, old games had Emergent Gameplay, new games don’t, but why?

Continue readingHow Fighting Games can Retain Players

Fighting Games don’t attract a lot of new blood. The majority of people who buy fighting games will never attend a single tournament for that game, never post about it online, and never interact with the community in any way. This means that the success of a competitive scene is tangential to the success of the game overall.

Fighting games being unpopular compared to other genres of competitive game is a demographic problem. Demographic problems require systemic solutions, not individual solutions. It’s easy to say that the problem is players who don’t have the drive to improve themselves, but a lot of people just bounce off of fighting games, even though they really want to go on an improvement journey. Fighting games can do a lot structure themselves to get these new players on the right track to understanding the game.

Magic the Gathering went through a similar issue early in their game’s lifespan. At first, they catered to pro players, and the game started to slowly die as MTG became more complex and more irrelevant to beginners. MTG ended up revitalizing themselves by decreasing their investment in competitive play, and instead focusing on creating appealing characters that people could connect to, and an easy introductory experience for beginners.

Wizards of the Coast called the non-competitive kitchen table players, “The Invisibles” because they don’t participate in the broader community, yet they make up the majority of the consumers. This is the case for every game or media product. The majority of a game’s fans will never ever participate in an observable way, but they’re the people who are the backbone of your sales, and they’re the people who filter into the competitive scene. Therefore, having an approachable game creates a more healthy and active scene for everyone.

Continue readingVisualizing the Skill Curve

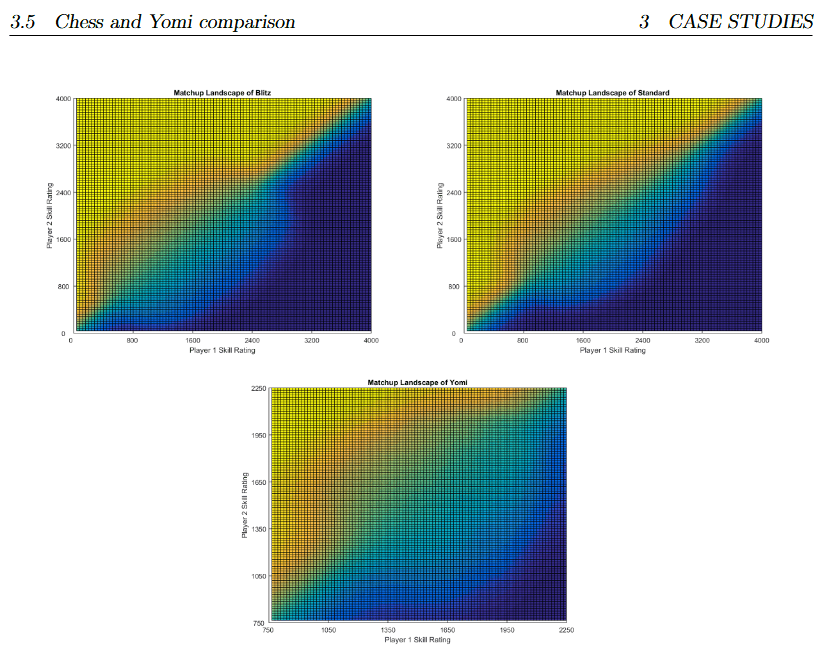

Recently in my discord, one user, Hambone, linked a study related to skill rankings in Blitz Chess, standard Chess, and the card game Yomi by David Sirlin, and how well those rankings correlated with win ratio. You can read the full study here. From it emerges this amazing chart:

This chart is a depiction of a game’s consistency across skill levels, with a spectacular illustration of how there are certain bottlenecks where consistency goes up and down. (for those with color blindness Player 2 winning is represented on the graph as yellow, losing as dark blue. Slight wins are orange, slight losses are light blue, and 50:50 is represented as teal). It’s worth noting that the skill ranking of an average player is 1200. From this chart, we can intuitively extrapolate a number of conclusions, but first lets make some observations: We can see that Yomi is less consistent across all skill levels than either variant of chess. We can see that chess has a short period near the bottom skill level where better players very consistently beat worse ones, then there’s a free-for-all near mid-low level, and another bottleneck at higher to top levels of skill. We see a mild version of this trend even in the yomi chart.

From this we can conclude that aspects of these games make them more or less consistent. From personal experience, I’m going to put forward that the big thing that makes a game consistent is execution testing, a style of game that I call an “efficiency race” (eg. racing games, games that directly compare a skill that is dependent exclusively on you and nothing else). The things that make a game less consistent are Randomness, and unweighted Rock Paper Scissors (eg. games of chance and games with hidden information, where you directly interact with your opponent). For example’s sake, there are some games where you cannot become consistent, such as a pure coin toss. The graph for this game would be teal (50:50 odds) across the entire chart. A hypothetical perfectly consistent game, where the better player always wins, would be a perfect split of yellow/dark blue directly across the diagonal center line, with almost no teal.

Continue readingDunkey Gets Dunked On

A friend on twitter was confused when I said Dunkey wasn’t a good reviewer recently. I asked him to pick out the video he thinks is Dunkey’s best review and I’d go over it. He picked Dunkey’s Mario Sunshine review, from this year. I know I said I wouldn’t do any more critic critique, but here you go. Hopefully this is better than any of my old stuff.

My biggest criticism of Dunkey is that he’s not a good critic, but he acts like he is, even though he does nothing fundamentally different from anyone at IGN. He’s part of the group that hates corporate reviews because they’re fake, not because they lack depth/insight, but he acts like being fake and lacking insight are the same thing (because he can’t tell the difference), so when he does an “honest” review, he thinks it’s automatically deep/insightful, because he has no idea what that actually means. The crowd that hates modern game reviews don’t hate them because they have a discerning eye. They hate them because they’re hearing the “wrong” things get praised/criticized. Dunkey praises/criticizes the things this crowd wants praised/criticized, so he gets treated like a good reviewer, even though he does the exact same thing as IGN. Same process, different conclusions, both bad reviews. Dunkey frequently has correct conclusions (relative to that crowd at least), but always bad reviews. You’re not a good reviewer unless you show your work.

Continue readingFPS Boss Fights Don’t Have to Suck Ft. Durandal

Editors note: This is another guest post by Durandal, though I wrote most of the paragraph on encouragement/discouragement and push/pull. If you’d like to submit a guest post, contact me on discord.

Boss fights involve fighting against one or more enemies that are usually harder than what came before in the game. Story/gameplay-wise they’re an effective way of setting the climax for a level or chapter, which is why they’re so widely used. Many genres like beat ‘em ups, platformers and shoot ’em ups all often feature great boss fights, like Credo in DMC4, Death in Castlevania 1, and the Battleship in Contra 3. But then you have bosses in first-person shooters.

In the 28 years since grandpa Wolfenstein 3D, there has been no truly good FPS boss fight. Instead you get playing peekaboo with (hitscanner) bulletsponges (such as Hans Grosse in Wolfenstein 3D and the 2009 reboot, the final bosses of Wolfenstein: TNO, TNC, and Youngblood, Makron in Quake 2, Tchernobog in Blood, the Battlelord in Duke Nukem 3D and Forever, Splitter Crow in TimeSplitters: Future Perfect, The Destroyer in Borderlands 1). You get the inoffensive bulletsponges which you circlestrafe to death (the Overlord, Cycloid Emperor and Cycloid Queen in Duke Nukem 3D, the Skaarj Queen and all Titan fights in Unreal Gold, Fontaine in Bioshock 1, almost every boss in DUSK, AMID EVIL, and the Shadow Warrior reboot). And at worst you get puzzle bossesthat play nothing like the rest of the game and expect you to figure out a puzzle to beat the boss (the Spider Mastermind in Doom 1 when pistol starting, the Icon of Sin in Doom 2, Cthton and Shub-Niggurath in Quake 1, the final bosses in Serious Sam: TFE and BFE, Nihilanth in Half-Life 1). Continue reading

Getting Over It With Bennet Foddy Review

Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy (GOI for short) is the absolute limit of how far you can get with a single game mechanic. The only mechanic is moving around a hammer, attached to a man in a cauldron.

With this control scheme you can push and pull yourself along the ground, pull yourself up using holds, fling yourself, swing under holds, pogo to launch yourself, and so on.

This method of control is incredibly sensitive, and fiddly, but the game ramps up to requiring you to use it in extremely precise and demanding circumstances, at high risk of losing your progress.

GOI can be incredibly frustrating, because there are no permanent checkpoints, and many of the toughest challenges set you up to lose massive amounts of progress. Playing the game at all with it’s strange and difficult control scheme seems impossible, so redoing the incredibly precise tricks it has you perform can seem impossible.

Mirror’s Edge Review

This is part of my 5×5 review series. I’m going to try to review every game in my 5×5, available on the About & Best Posts page. Photos courtesy of Dead End Thrills and gifs courtesy of CabalCrow from my discord.

Mirror’s Edge is one of my most-played games because I used to speedrun it. My best time was about 55 minutes, which isn’t that impressive, but in the process of learning to speedrun it, I learned a lot about what makes an interesting speedgame. I also had a massive amount of fun learning the various techniques involved in the game, from the easy to the hard, and refining my run.

On this blog, I define a game as a “contract” that the player agrees to play under, either a contract with themselves or other players, as in a multiplayer or co-op game. With this in mind, the game isn’t necessarily the software you play with, but rather how you choose to use it, and different players can play different games with the same software. Speedrunners are playing their own game with the software relative to everyone else. For that reason my blog doesn’t tend to focus on the “speedgame” for a piece of software, but rather the “canonical” game that represents more of the lowest-common-denominator idea of what the public thinks the game is, which is usually something closer to what the developers intended than anything else. What’s possible in the speedgame sometimes can influence the “casual” game (what speedrunners call the more default ruleset), but it’s very situational per-game. Continue reading

Isomorphism & Asymmetry

Isomorphism is a concept in Graph Theory, where 2 graphs, if they have the same nodes, connected by the same edges, are the same graph, no matter how they’re shaped. Basically this means that if two seemingly different systems have the same shape, they’re actually the same system.

One of the most popular examples of this is the Rest system in World of Warcraft. MMOs are known for being addictive. You pay a subscription to them, so there’s only so much time before your subscription runs out, and you want to get the most out of it. To avoid encouraging players to play constantly, many MMOs implemented penalties for playing continuously, to incentivize players to log off. Naturally players didn’t like having their xp gains drop to 50% as they continued to play during the WoW beta, so the developers tweaked the interface so that the “unrested” penalty became a rested bonus, granting 200% xp gains. The actual numbers didn’t change at all, but player reception to them did.

Continue readingKill Your Sacred Cows

A long long time ago, I used to like Zelda, Okami, and Mad World, among others. I thought they were good games, and I never really questioned it. I remember before I played Ocarina of Time how much everyone said it was the best game of all time. There were memes back then of the OOT box, with a warning label, “Warning: Playing this game will make every game you play following this a slight disappointment.” I played OoT and somewhere at the back of my head thought, “huh, it’s not the greatest game I’ve ever played”, but I completed it, and all the sidequests, and never looked back.

I never really questioned liking the Zelda games until Tevis Thompson’s essay, “Saving Zelda” released in 2012. Dark Souls and Zelda: Skyward Sword had released around the same time the previous year, and I came home from college and played them both over winter break, jumping back and forth between them. I was completely on the hype train for Skyward Sword. I’d played a demo of it at New York Comic Con. I pirated that demo shortly before release, and I was hyped to see motion controls finally get their moment in the sun after being disappointed with how Twilight Princess used waggling as a substitute for the sword button. Despite that, with the actual game in my hands, I found myself playing a lot more of Dark Souls and I didn’t really know why.

Then “Saving Zelda” dropped a couple months later, and I read it, thinking, “This is ridiculous, Zelda’s a great series. Everyone loves Zelda. Skyward Sword is amazing”, but it planted the seed of doubt.

Continue readingDesigning AGAINST Speedrunners

Speedrunners are terrible. They ruin games for everyone, and love to talk about how your coders are buffoons when they perform intricate tricks with elaborate setup and tight inputs that no ordinary player would ever think of doing, let alone be able to perform. Here’s how to drive these pests away from your games.

First, make an inaccurate ingame timer. Include load times (multiplied by 2, so now everyone needs to buy an SSD), cutscenes, character creation, time since the game was launched. Hide it until they beat the game so they can’t reliably check if it’s accurate without cross referencing another timer.

Next, make file management annoying, or impossible. Utilize cloud saves, have events in one save affect events in a new game. Store savedata in the game binaries, encrypted, so they’re difficult to access, and difficult to modify. This makes starting completely fresh annoying.

Continue reading