Design Space is tricky to define, because it’s the water we swim in. Mark Rosewater (who probably coined the term) says that design space is roughly how many new cards can be made from a new mechanic. A mechanic that affords a large design space interacts well with the rest of the game and allows them to create a wide variety of new cards. In other words, Design Space defines how many differentiated game elements (cards, weapons, characters, moves, enemies, obstacles, projectiles, etc.) you can create from the base mechanics of your game.

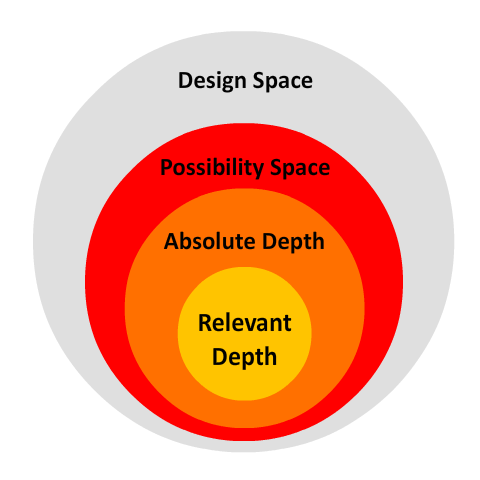

Relative to my 3-filters theory of Depth, Design Space acts almost like a 4th filter, above Possibility Space. Design Space defines which possibility spaces can even be made with the mechanics and attributes you have available to you. Possibility space is all the things that can happen in your games. Design space is all the possible games (or content) that you can make with the mechanics and systems you have chosen. In this way, game designers strive not only to create possibility spaces that are rich with possible game States, but design spaces that will allow them to create elements that enable those possibility spaces to contain a multitude of game states. A more richly detailed character allows for a more richly detailed environment for that character to interact with.

In more practical terms: Design space is like adding another axis to your game. You can progress linearly from A to B, but with a 2nd dimension, you can go around things. And with a 3rd dimension, you can go over or under them. Design Space is what enables Orthogonal Design, design where multiple variables or attributes of an element are tweaked at once to create a disproportional relationship to other elements. Put more simply, orthogonal design is designing elements that go off in a different direction than the other elements.

If you have an RPG where you can only deal damage, then fights are just about who deals more damage faster. If you have an RPG where you can heal and deal damage, then fights are about dealing damage faster, and healing when you’re low. There’s now an element of risk over whether or not the next hit will knock you out. If you add buffs, debuffs, type weaknesses, and turn economies, then you have many more ways to engage in a fight. There is now more room for options to be orthogonal to one another, to accomplish unique purposes without simply being better or worse damage dealers in a linear way.

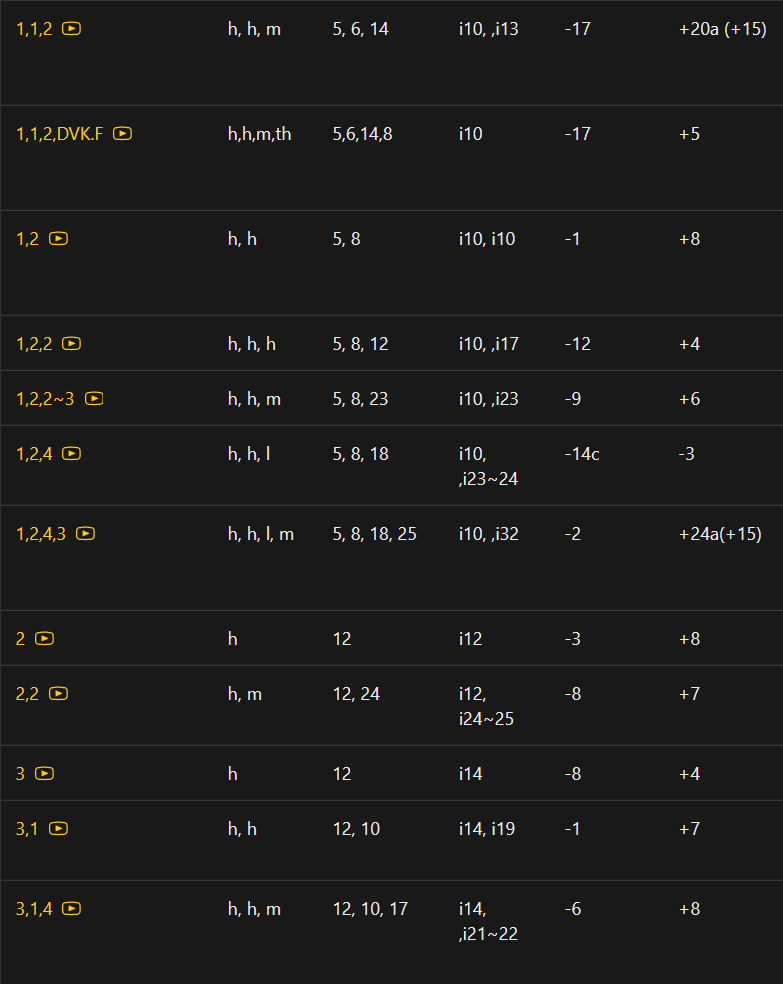

You can see orthogonality in the design of Pokemon moves. Your starting moves early in the game are fairly simple and linear, like tackle, vine whip, peck, and water gun. Later moves tend to have secondary effects, like inflicting status effects, buffing or debuffing Pokemon, always going first, never missing, dealing double damage if you’ve been hit, and so on. They also have a unique type, power, accuracy, and PP value. These help give every move a unique role, making them orthogonal to one another. Because different Pokemon have different combinations of types, abilities, and move pools, this helps make each Pokemon species unique and orthogonal to one another.

MTG Creatures

Each Magic the Gathering creature has three attributes: cost, power, and toughness. These create a design space wherein you can potentially create a very large number of different combinations of these three traits.

Once a set of cards has been created with these three attributes, the possibility space of the game is every possible configuration of those cards that can be arranged on the board, or in people’s hands, or graveyards, or libraries. In this way we can see that possibility space is downstream of design space. The design space of these three attributes includes many cards that have never been and will never be created, but the possibility space of those cards that have actually been created is much smaller.

Why haven’t certain combinations of these traits been created yet? Because having a one mana 12/12 would harm the relevant depth of the game. In order to make a design like that work, you need more design space than simply these three attributes. We can see this in the design of Phyrexian Dreadnought, which requires you to sacrifice creatures whose power adds up to 12 or more. Through the additional design space of triggered abilities, and sacrificing creatures, it is possible to create a one mana 12/12 without harming the relevant depth of the game.

Another interesting thing about Phyrexian Dreadnought is that this requirement to sacrifice creatures is a triggered ability, rather than an additional cost (they hadn’t entirely worked out how additional costs should work by that point in the game, and a creature with an additional cost wouldn’t be printed for another 3 years). This enables a lot of possibility space that otherwise would have gone unrealized, because Phyrexian Dreadnought briefly exists on the battlefield before its effect sacrifices itself. This means that Phyrexian Dreadnought’s high power and toughness can be taken advantage of by instant-speed spells that reference those attributes, such as Momentous Fall or a Fight or Bite spell (deals damage to an opponent’s creature), or a creature ability that references power and toughness. You can also take advantage of this by countering the triggered ability to get a 12/12 for much cheaper than it would normally cost. The institution of additional costs onto creatures acts to purposefully limit this possibility space, in order to better balance the game, preserving relevant depth.

New Magic the Gathering sets include new mechanics, which aim to open up new possibility spaces that can be realized in the future as new cards are made. For example, when the game was originally released very little was done with the removed from play zone that is now called exile. Now there are a variety of different effects that cast spells from exile or store cards in exile until later, such as foretell, plot, cascade, hideaway, suspend, imprint, adventure, warp, and airbend. Originally, spells strictly required mana in order to be cast. Now, there are a variety of spells with casting costs that do not require mana, such as force of will, force of negation, gush, fierce guardianship, flare of cultivation, and spells with the delve, convoke, or affinity keywords.

Real-Time Games

Design space tends to be easier to understand in turn-based games compared to real-time games, which simulate physical space, or which have a timing or dexterity component. This is because turn-based games tend to have more clearly enumerated mechanics, resources, and other attributes to their game elements. Real-time games can create mechanics that engage in multiple behaviors over time and space, which can be hard to think of in a more abstract way. Can you nail down the design space of Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy without having it explained to you? (hint: look at the different types of holds you need to grab onto across the game, and how they’re sequenced)

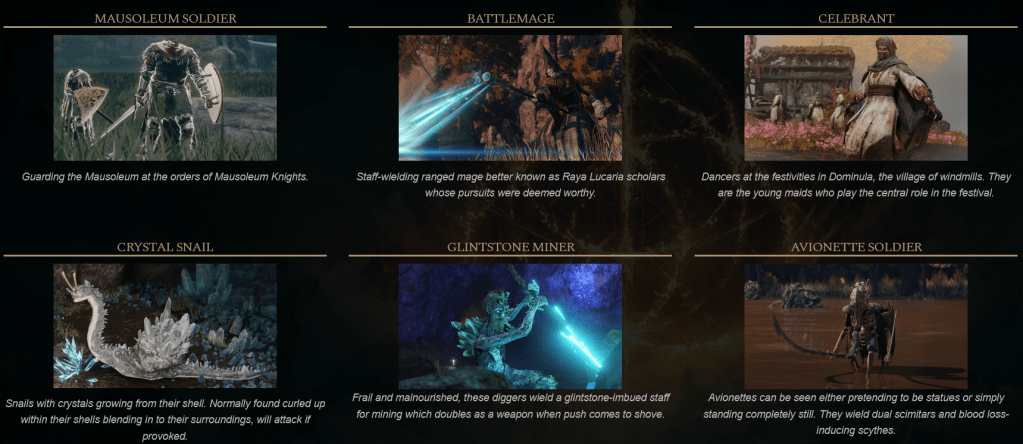

For real-time games, you can picture design space as, “With these mechanics, how many different levels can I make?” How many different jumps are possible in Mario versus Celeste? How many different combos or pressure situations for a fighting game? How many Dark Souls enemies and areas can I create?

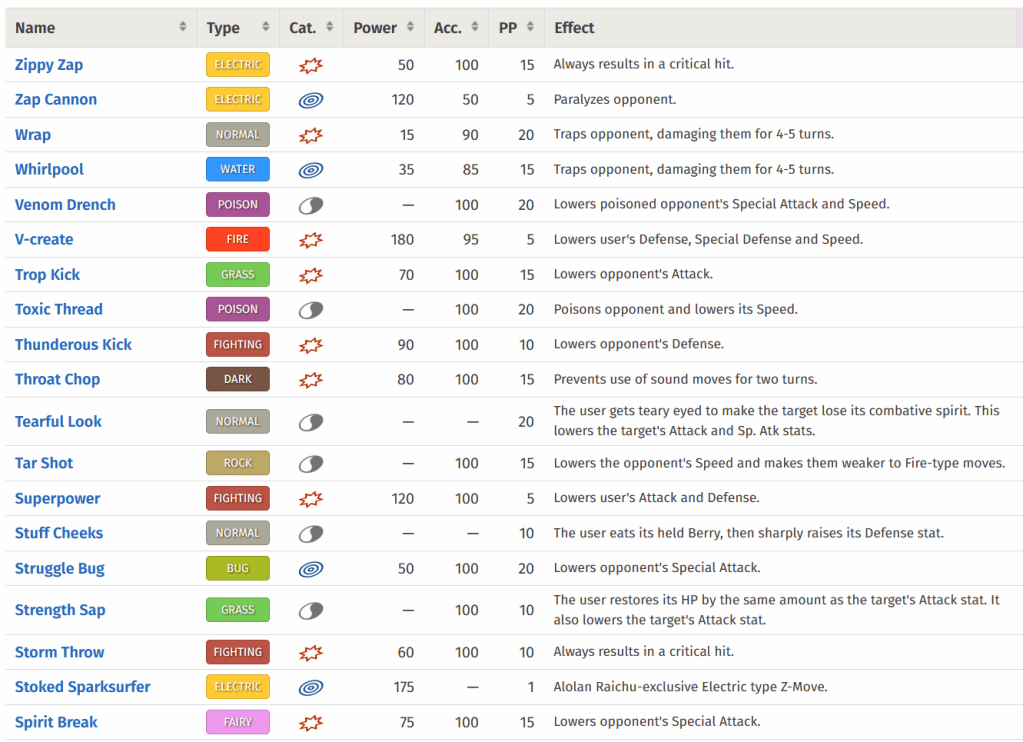

I think the Soulsborne series is a fairly interesting case study for design space, because it has retained fairly consistent core mechanics since Demon’s Souls all the way to Elden Ring. Across the 6 Soulsborne games that exist, we can see a very thorough exploration of different enemy, boss, and terrain types within a relatively consistent design space. One of the big ways that design space has expanded across the games was the reduction of fall damage in Dark Souls 1, allowing for more vertical level design (not that Demon’s Souls didn’t try, to disastrous effect!).

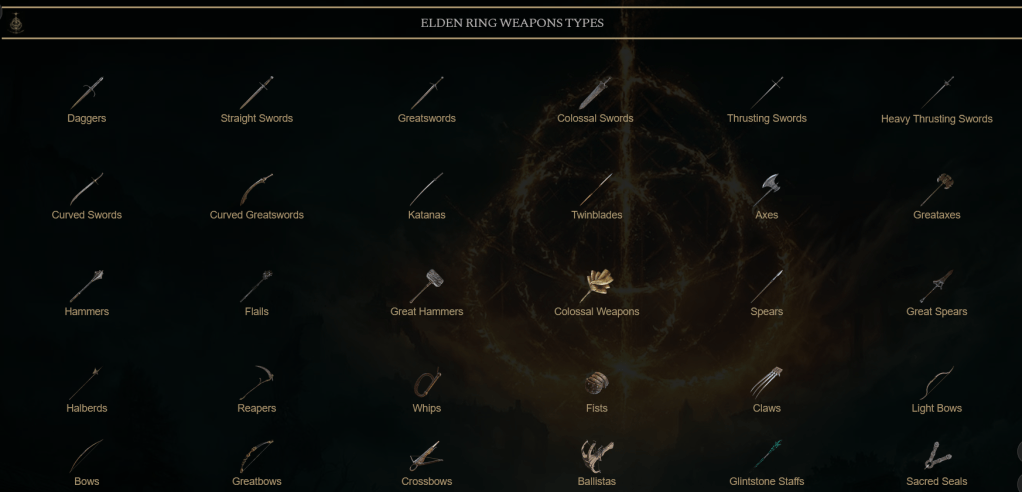

We can see design space applied in the traits of different weapons, spells, enemies, and obstacles. Each game has a roster of weapons, with unique animations and stats. They can be faster or slower, cover wider or narrower areas, scale with STR or Dex, deal more poise or less per-attack, and knock down smaller enemies on certain attacks too. From Soft have created all of these different possible weapon traits for their design space, and then fleshed that out into discrete content.

Something that is noticeable across the series is that over time, telegraphs for attacks have become more delayed and difficult to read. I believe this is a consequence of not expanding the design space for enemies beyond melee attacks and attack strings. When they don’t have another way to make enemies and attacks unique and differentiated, they are forced to stretch what they have.

Fighting Games

Comparing the design spaces of Tekken versus Street Fighter can be fairly instructive. Tekken determined fairly early on that it would limit its design space to only melee strikes, arranged into different strings. Most of these would be minus on block, plus on hit, and no faster than 10 frames. Street Fighter meanwhile determined that it would allow for a variety of special moves, like fireballs, or flaming uppercuts, or spinning air kicks that move across the stage. It also didn’t set a minimum startup speed for attacks, and any attack could be plus or minus on hit or block (in earlier games, they tended to use the same stun for both). Rather than comboing through preset strings, Street Fighter characters can cancel a number of their attacks into special moves or link frame advantaged attacks together.

This means that when Tekken makes a new character, they tend to be more limited in the tools that they have to differentiate characters, where Street Fighter characters tend to be very dramatically different from prior ones. There’s a big difference in the fighting style of Ryu, Makoto, Blanka, JP, Dhalsim, and Cammy (I’m intentionally ignoring characters with unique meters), and comparatively a much smaller difference in even Tekken’s wackier characters like Yoshimitsu.

This isn’t to say that Tekken isn’t a deep game in its own right. Tekken chose to deliberately emphasize aspects of its design space that Street Fighter didn’t, like small gradations in frame disadvantage & startup time, and the difference between standing and crouching. Sidestepping along with Stage Hazards add design space and therefore possibility space that Street Fighter lacks. However, the limitations in design space for its characters mean that Tekken tends to revolve much more heavily around its core systems, and Street Fighter tends to revolve more heavily around its matchups.

We also see games that expand on the design space of Street Fighter with anime fighters and King of Fighters, which add new movement tools, combo possibilities, meters, and more complex projectiles. In turn, this tends to have a deleterious effect on some of the relevant depth involved in simple grounded footsies. It’s a tradeoff. It’s a good thing that both of these styles of game exist, so that players can experience these different possibility spaces, created through different design spaces.

Conclusion

Content is the realization of Design Space, which enables the Possibility Space that players have available to play with. When a design space is thoroughly explored, your game will feel “full”. When it feels like there is more you could have explored, then players will feel like there is something lacking. When you exhaustively tread over the same design space (such as in many kit-bashed open world games), players are likely to feel bored or exhausted from repetition.

The lens of Design Space isn’t equally applicable to all games, in part because not all games have as clear a division between mechanics and content. Not all games reuse and modify mechanics and context. You can look at Action Puzzle games, like Tetris, Puyo Puyo, or Panel De Pon to see examples of this. These games have been rereleased and remixed with mechanical tweaks, but it’s hard to look at any action puzzle games and talk about the design space that it is exploring. Many board games are similar, such as Go or Reversi. In contrast, it’s easier to talk about design space with many card games, such as the variants of Poker, or the genre of Trick-Taking games. In a similar way, it’s difficult to really quantify the design space of most sports, like Soccer, Tennis, or Basketball.

Video game bosses also tend to operate in this territory, being made bespoke for an encounter and having their own rules and logic, rather than being reconfigured from the wider design space defined by the other game elements. Shmup bosses and 3d platformer bosses are great examples of these, where action game bosses tend to resemble the rest of the design space more.

Games can also create completely bespoke assets for everything, and never reuse, remix, or reintegrate any aspects of their design. Many puzzle ‘games’ do this, which is fine, because puzzle games aren’t necessarily trying to create possibility space and relevant depth for players. I don’t recommend this approach if you are trying to make a game, because elements that lack connections between one another tend to lead to shallow possibility spaces.

Design Space offers us a lens to systematize game creation using compositional design patterns, and determine where we may be falling short in content development or creating fundamentally shallow mechanics. It also offers us a rubric for not just developing existing games, but also sequels, and other content expansions.