The concept of depth is interesting but very abstract to me. Can you give some in-game examples games with depth done right?

https://critpoints.wordpress.com/2016/08/10/games-for-learning-about-depth/

Doing examples of depth is tricky because games are complicated. A game being deep means it has way more depth than its competitors, so it’s especially complicated. So to explain depth I tend to use simple examples, like mario’s multi-height jump, or the way you can double jump at any point during a jump, and hope that people can extrapolate from there.

So lets try a more complex example for a change, imagine a fighting game like street fighter. Depth is the sum of all the possible states, minus the redundant and irrelevant ones, so what are all the states possible in a fighting game? First, think of all the different possible positions both players could be standing on the stage. They could stand in the corners, mid-screen, close together, far apart. Imagine every possible individual position on the entire screen that they could stand, then the combination of every possible position they could both stand relative to each other.

So first there’s some redundancy there. Fighting game stages are (mostly) symmetrical. This means that if one dude is in the corner on one side, it’s the same as them being in the corner on the other side. So half of those possible positions in the earlier example are redundant.

Next, fighting game characters can jump, so imagine every possible position they could jump from and to across the stage. Imagine every possible position they could occupy at any given time in the air, and the velocity they’d have applied to them at that moment in time.

Next, think of all their moves, think of how they could perform any of their moves in any of these possible positions and relative positions across the entire stage. Think of how they could both be performing moves at different times relative to each other.

Then think of all the possible amounts of meter they could have at any given time.

If you’ve ever played with an emulator before, you can think of every one of these combinations of things as a save state. Imagine the way all of the things above can be combined to create a tremendous number of distinct save states. The idea of depth is to figure out exactly how many different possible states a game can contain, then to weed out the states that are either effectively the same state, or are made irrelevant by balance issues between different elements, or are unrelated to the goal of the game.

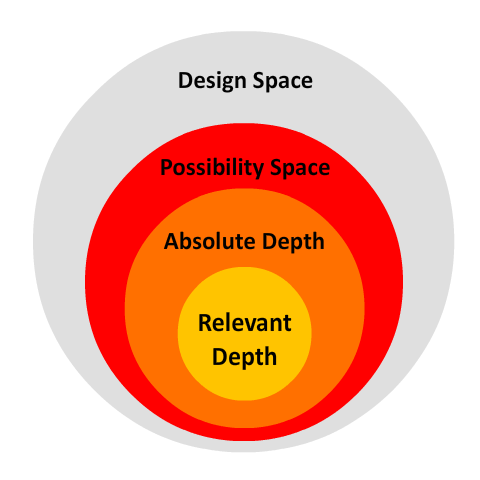

The more complex the game, the harder imagining all this is. Complexity does not necessarily create depth, because a game can be complex, but highly redundant, or most of that complexity could be irrelevant, but increasing depth means either increasing complexity, or better leveraging the complexity that is already there. Complexity creates state space, and depth is a limited selection of that state space. To increase depth, either the state space needs to get bigger, or more of it needs to be useful.

So lets get back to redundancy and irrelevancy. Just because a game has all these states doesn’t necessarily mean they all matter. One might point out the obvious: if a game runs at 60fps instead of 30fps, doesn’t that mean that it has twice the number of possible states? Since the game is stepping half as much each frame, and therefore can pass through twice as many positions? While this is technically true, the majority of those states are so barely different that we can say that they’re effectively redundant. So a game isn’t going to double in depth by going to 120fps. For the majority of cases (every single case you can imagine), FPS can safely be disregarded as a source of depth, even though it technically multiplies state space.

However theoretically this isn’t always the case. A 5fps game is probably fairly limited in what it can express in terms of intervals of timing. A bump up in fps for a 5fps game would probably dramatically improve the fidelity of interactions and range of spacing/positioning/timing choices a player can make. The principle here is that converting a range from being more discrete to more continuous does increase the depth of the game, but as the range becomes more continuous, there’s a falloff in how much depth you actually gain and past a certain threshold you’re not gaining depth anymore. The advantage of discrete ranges is they have more clear differentiation between states, a lack of redundancy, and the advantage of continuous ranges is they have a higher number of total states. Go and Chess don’t let you move half a square, they have totally discrete states, which means that no state is redundant (unless it’s a mirror or rotation of another state).

In a fighting game, you might be able to stand at an infinite number of precise positions relative to your opponent, but if you’re within range to do a move, it doesn’t really matter that much if you’re slightly closer or slightly further, unless that distance changes what moves you’re in range of or in range to do. In Smash Bros, being slightly closer or further can change which hitbox of your move hits, changing the effect of the move slightly. In this way Smash Bros is frequently able to make less of its state space redundant than might be true otherwise. So this infinite continuous range of positions is in reality limited to just the positions where your options or your opponent’s change, give or take a bit (after all, you could have them engulfed deep in your range, or at the very edge of your range, and the difference between those is worth accounting for, even if it doesn’t count for much).

Reducing redundancy is about making every state count, about making every state have a functional difference from all the other ones.

With relevancy, you might have a ton of distinct states, but many of them might have nothing to do with winning and many of them might be things that nobody ever does, either because they’re sub-optimal, or because they just don’t know those states exist. If redundancy is a systems-wise evaluation of depth, then relevancy is depth as it pertains to the playerbase. Relevancy is a reflection of the balance of elements, player opinions, cosmetics, and simply what players even know about a game. If state space and non-redundant state space are unchanging then relevant state space is not just in flux, but it’s different between different people, and the same group of people over time.

Relevancy is probably most impactful when it comes to balance. There’s a lot of different types of balance to consider. There’s balance between characters, balance between weapons/equipables, balance between moves, balance between strategies, balance between playstyles. The thing you want to foster is interesting choices, making it difficult to choose between one thing and another. You want to give people convincing reasons to pick between these things, make it so everything has a situational use, a reason to use it over other things depending on circumstance, but you also don’t want to make it so there’s only one option for any given situation. A basic trick some games use is to create situational factors that change over time, to change what the best option is, so you’re not always doing the same thing, but if you’re really only responding to each situation with that situation’s specific solution, then that obviously doesn’t have as much depth as having competing options for any given situation. If the options compete, then people will choose inbetween the two, meaning more relevant states.

So the thing with balance is, it’s the case where increasing the state size of the game, where adding new elements, can actually decrease the depth of the game. Keeping things in balance is about making sure they have tradeoffs, so nothing is ever a flat-out better version of something else, but also that they compete with one another, so that while you might use both options situationally, they never become the undisputed master of their particular domain for any situation. You don’t want any character to be the best, you don’t want any move to be the only thing people use, you don’t want people to play defense only or offense only, you don’t want people to only play with sweep and throw.

Balance is also a struggle between making sure all the elements are in line with all the others, and making sure they’re differentiated in function. An easy way to balance is to make things more homogenous, but if you do that, there might be more relevant states, but there will also be more redundancy, resulting in overall lower depth. So you need to make sure everything is as “strong” or as relevant as everything else, but you need to make sure it stays differentiated in the process.

Choosing relevancy as the word to describe depth as it relates to players is also helpful because it can represent shifts in how the game is understood. A game might have a high number of non-redundant states, but players might think it’s a shallow game simply because they don’t know how to play the game. There can be new discoveries about the game that make the game deeper, like finding a new technique that combines with every other mechanic in the game. Or there can be new discoveries that actually make the game less deep, because they overshadow other mechanics, are poorly balanced. Or they could do both, and the game might end up gaining new relevant states and losing others and come out as a better or worse game overall.

In this way, games can become deeper over time as more is figured out about them, or shallower as they get closer to being solved, and you can examine how deep the game is relative to a group of players, like low level players who may not play the game like the pros do. Some states might never be relevant because they’re too hard for anyone to access, so there might be a TAS-only trick that is not part of the game’s depth because it never comes up when a human plays the game.

Now, this might lead you to think, “Okay, so does this mean that players can just define depth as whatever set of states they want?” The way I’d frame it is that the relevant group of states in a game is not chosen by any deliberate decision of the players, it’s a consequence of the way the game is designed, and given a devoted playerbase, the relevant group of states will be arrived at inevitably. The players don’t choose who the top tier character is, it’s a product of how the game is designed, and how much they know about the game. Meaning that even though the relevant states are defined by the playerbase, the way they’ll end up is baked into the game design and revealed when it comes into contact with the players.

This means developers can deliberately design the game to develop differently over time when it comes into contact with the playerbase by making things more/less obvious (also called affordance), and it also means that if you want to patch the game for balance later on, you need to wait for players to figure it out, so you can see what the relative strength of various elements actually is, because it’s an emergent property of the interaction between the game and the playerbase, which you can’t totally predict in advance.

There might also be states that don’t actually affect the outcome of the game, like picking a color for your character, or particle effects that cannot influence other game objects. These are irrelevant to the depth of the game, so irrelevant sums them up fairly well.

So that’s a lot of stuff to keep in mind, and it can be a bit hard to visualize for any particular game, but all of it provides a framework for understanding the impact of nearly everything you can create in a game. You want to build the largest state space possible, make sure as many states are differentiated from other states as possible, and as many of the states as possible commonly occur in play.