There is a common misconception in PVP game design that melee attacks should be slow and reactable in order to make it fair for your opponents to play around them. The problem with this is that it fundamentally breaks the core game dynamic, resulting in a game where doing nothing is the best option.

PVP games focused on Melee combat must have some way to either hurt the opponent that they can’t react to, or a way to set up a situation where they cannot avoid getting hurt that they cannot react to. If a game doesn’t have this, it will result in a complete stalemate. A more broad way of formulating this is: A PVP game must have a way for any player to advance the game towards a conclusion where one side wins, and any action that would prevent this advancement must be dependent on Rock Paper Scissors Guesswork, or have a chance of failure.

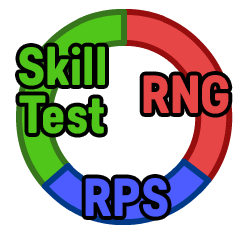

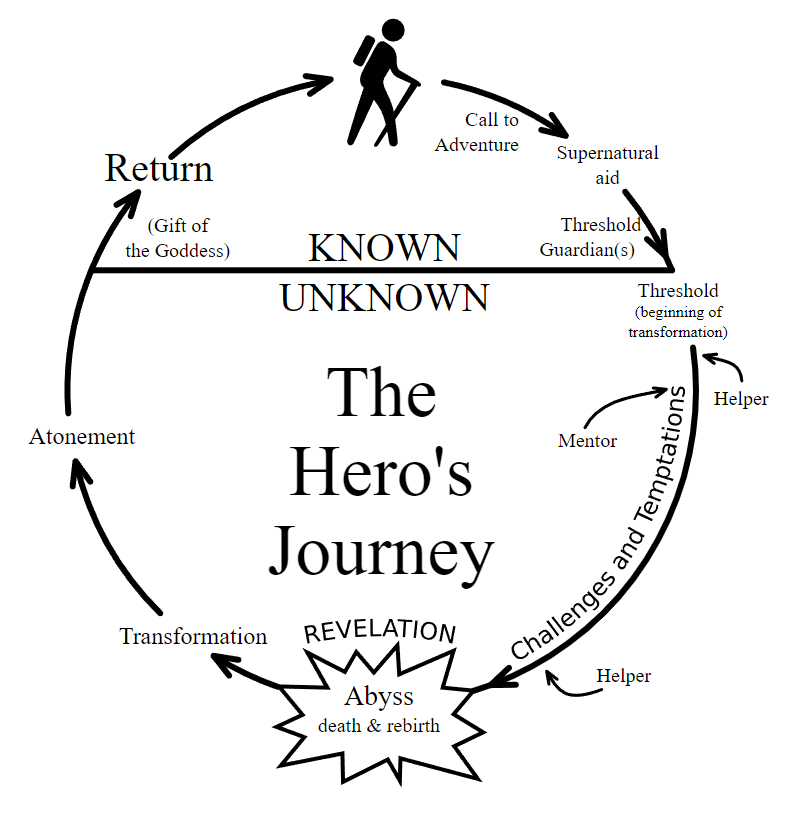

I believe that all PVP games are a complex (or not so complex) combination of 3 simpler games: Rock Paper Scissors, Skill Tests (or efficiency race), and Random Number Generation. Everything PVP is a game of chance, a game of skill, or a game of prediction; or some combination of the three.

Melee combat games are games of largely RPS. Melee strikes have a commitment, like a throw of hands in Rock Paper Scissors. And when they connect with an opponent, they will inflict hitstun, interrupting the opponent’s action. This means that different choices will counter one another, like in Rock Paper Scissors. This is a non-transitive relationship between different options and how many points they score. And critically: When you throw hands in RPS, you do it on the count of 3, throwing them simultaneously, so that neither of you can see which hand the other person threw.

Continue reading