So previously I’ve taught you How To Perform Fighting Game Motions, now lets learn how developers coded them. As far as I know, nobody has documented how to do this before, and it’s essential for anyone making a fighting game, or anything like a fighting game.

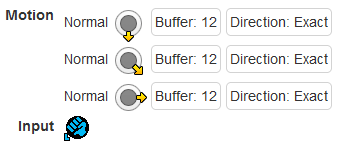

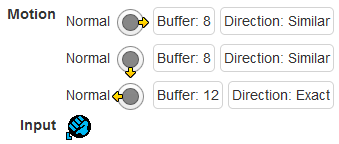

There is a website called SFVSim that catalogues change differences between versions for moves in Street Fighter V. This includes a lot of data on each move, including the input requirements.

This is extremely helpful for determining the logic involved for these motion inputs. The buffer on each direction determines how much time in frames is allowed to elapse before the next input is provided, or the motion becomes invalid. In other words, it determines how quickly you need to do the motion, and how much time you have to press the button after you’ve completed it.

Continue reading