I have a 4 factor model for move/option design in PvP games:

- Stake (how much you stand to lose by choosing this option, either in costs or penalties)

- Reward (how much you stand to gain if this option succeeds and stand to gain regardless)

- Difficulty/Chance (the likelihood that the option will be successfully executed)

- Counterplay (what range of options this move beats, and how hard/soft a counter)

The purpose of dividing across these 4 factors is to help illustrate to designers the different levers they can pull, instead of focusing purely on a linear risk/reward relationship.

It’s common for a lot of designers to get stuck thinking that everything risky has to have a proportionate amount of reward, and everything rewarding has to have a proportionate amount at stake. Having lopsided stake/reward relationships is possible and healthy when the difficulty and counterplay are considered.

A subtle factor of this model is that cost is a type of risk, and therefore something you put at Stake. When you pay a cost, you’re risking that that investment won’t pay off. Therefore An upside of this model is that it separates Risk from Difficulty/Chance of Success, which are often conflated. “This move is risky, because you’re likely to mess it up.” By separating Risk out into Stake, Difficulty, and Counterplay, we can think more carefully about how each of these different factors play into an option’s design, and we have a wider design space for option design.

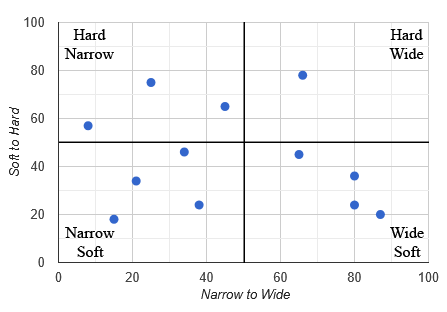

Within counterplay there is a lot of nuance to how counters can be designed. I’m going to identify 2 spectrums:

- Hard vs Soft

- Wide vs Narrow

A hard counter is one that is guaranteed to always shut down the option that it counters. A soft counter is one with more wiggle room.

A wide counter can beat a wide variety of options. And a narrow counter can only deal with a very specific one.

By dividing counterplay across these two axes, we can see the relative strengths and weaknesses of different moves and intentionally alter the counterplay of moves relative to our needs.

Continue reading