A lot of people who know me know that I don’t especially like 3d Zelda games before Breath of the Wild, but explaining why, and who is responsible for those design decisions is a long long story.

The Arcade Roots of Zelda

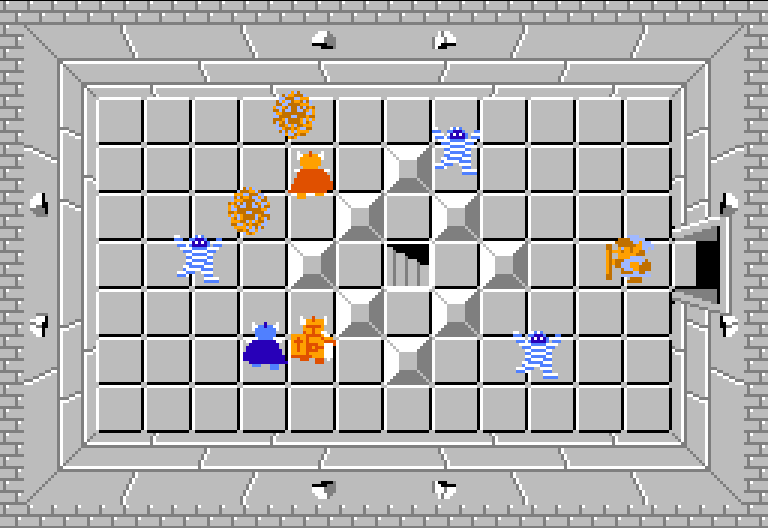

The Legend of Zelda (hereafter, Zelda 1) was an Open World Action game. In retrospect, it’s been called an action-adventure game, but understanding it as an open world action game is probably more fitting to the context in which it originally arrived. It was designed by Shigeru Miyamoto, who was inspired by childhood adventures, where he would travel on foot across the countryside and try to map out the places he’d been to. He also was attempting to distinguish it from Super Mario Bros by making it nonlinear, top-down, and a number of other ideas.

Shigeru Miyamoto was a very prominent designer for Nintendo during their early era, having designed Donkey Kong, Mario Bros, Donkey Kong Jr, and Donkey Kong 3, which were all arcade hits. Going into the design for games on the NES, he had a strong bedrock of experience in Arcade game design, and brought that experience with him into designing NES games, leading to Nintendo’s NES games having a strong action focus, utilizing reflexes and timing for their gameplay, instead of navigating menus and solving puzzles.

This arcade focus is in opposition to the PC games that were developed at the time, which tended to be slow, to rely on menus for gameplay, and have many complex configurable variables, as well as relying on save systems to store progression. In many ways, Zelda 1‘s pitch was, “Here’s all the fast twitchy action gameplay of arcade games, but in an RPG you can play at home!” The Nintendo Fun Club newsletter specifically advertised it this way. Over time, people would recognize that Zelda wasn’t really an RPG, and came to call it an Action Adventure game, but Action RPG was part of the original pitch for the franchise!

Zelda 1 was the first NES game to allow you to save the game, thanks to a battery pack inside the cartridge that preserved the memory after it was removed from the console. Prior games to Zelda 1 required the player to memorize passwords, or simply leave the console turned on and beat the game in one go, a lot like how games were played in Arcades of the time. I bring this up to highlight that Zelda 1 was a game that had arcade roots in its game design, but some of the home entertainment features of a PC. There were two strong design “traditions” at the time, between Arcades and Personal Computers, and the introduction of personal computer technology into home consoles would slowly shift the way console games were designed.

For Zelda II: Adventure of Link and Zelda 3: A Link to the Past, Miyamoto stepped down as director to assume just a producer role. Adventure of Link had an experience system, making it play more like an RPG than any other game in the franchise (and this eventually served as a core inspiration for Castlevania: Symphony of the Night), and it had a sidescrolling action mode for random overworld encounters and dungeons. A Link to the Past allowed you to farm rupees by cutting down grass, in contrast to defeating enemies, and it had a vastly expanded inventory system, with many more NPCs and more puzzles than prior games (though not many).

Eiji Aonuma (When Zelda Changed)

Eiji Aonuma joined Nintendo in 1988. He initially had small roles on a few Nintendo projects, and eventually got to direct Marvelous: Mōhitotsu no Takarajima, a puzzle adventure game, in 1991, shortly after the release of A Link to The Past. More than anything else, we should probably be looking at this game as the indicator of what type of designer Eiji Aonuma is, and what types of games he likes. Following that game, he went on to become the Enemy and Dungeon designer for Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

Eiji Aonuma is someone who hates the original Legend of Zelda, and has never beaten the game. I think this interview is incredibly reflective of his views on the franchise, so I will quote a large portion of it (Emphasis added by me).

My first encounter with Zelda occurred in 1988 shortly after I joined Nintendo. After studying design in college, I began work designing pixel characters. At the time, I didn’t have much experience playing games, and I was particularly bad at playing games that required quick reflexes. So, immediately after I started playing the original Zelda, I failed to read the movements of the Octorock in the field and my game suddenly game to an end. Even after getting used to the controls, each time the screen rolled to a new area new Octorock appeared and I thought ‘am I going to have to fight these things forever?’ Eventually, I gave up getting any further in the game.

The result was that I was under the impression that the Legend of Zelda was not a game that suited me. So what kind of games did suit me? Those would be text-based adventures. For someone like me who enjoyed reading stories, these were games that allowed you to participate in the story and letting you experience the joy of seeing your own thoughts and actions affect the progression of the story. Plus, these games don’t require fast reflexes and don’t require traditional gaming skills. So, I thought that if I were going to make games, I would like to make this type of game.

[…] In planning A Link to the Past, I kept playing basic actions that were completely unrelated to battling the enemies — things like cutting the grass, lifting stones to search beneath them, and using keys to open doors. In these, I discovered that I was proceeding through the game, and I got the same feeling I did when using command inputs to actively participate in the story of a text-based adventure. I realized that those same feelings, coupled with a sense of play control response, far exceeded what I could experience through command input alone.

So in realizing the types of control input response you could have while still pushing through the story, I realized that this was the kind of game I wanted to create. Unfortunately, at that time Nintendo still had need of my role as a designer, so my hope to create a Zelda-like game could not be immediately realized.

Two years later though, there was a project that gave me just that opportunity in 1996. The game was released in the overlap between the SNES and Nintendo 64 and for a variety of reasons it was never localized, so it did not make it to the worldwide market. But, this game called Marvelous was built upon the Zelda style of adventure events and was praised in Japan as an ambitious work that felt like a change to the Zelda-style gameplay. Now, I’ve never asked how Mr. Miyamoto viewed this game, so I can’t really make any claims about his thoughts on it. But, it was after this game that he instructed me to join the team to create Zelda.

I wasn’t involved with Ocarina of Time from the initial stages of development, but rather from the point at which the planning framework had already been finalized and work was beginning on building onto that framework. This project started off with multiple directors being responsible for individual portions of the game, which was a different style from the way EAD had developed software until then.

I became responsible for dungeon design and the design of enemy creatures in the dungeons. Of course, I felt it was strange that I, who was so terrible at fighting creatures in the original Zelda and decided that Zelda wasn’t the game for me, ended up working on enemy design. But, the type of gameplay used in enemy battles becomes an extremely important mechanic in Ocarina of Time, so there was really no way for me to escape it.

In Ocarina of Time, in addition to doing the dungeon design, I also took up the challenge of incorporating adventure elements into dungeons. By which I mean, giving the dungeon some type of theme, such as rescuing trapped Goron or hunting down the Poe sisters.

Aonuma serving as the enemy and dungeon designer for Ocarina of Time ended up significantly changing the direction of the Legend of Zelda series, starting with Ocarina of Time. Following his success at completing Majora’s Mask in a year, he was handed control over the series from that point onwards.

Across this interview, you can see that Aonuma is someone who doesn’t like reflexes and traditional gaming skills, he likes puzzles. He wants to make games where you solve puzzles to progress through the story. And this is how the Zelda series progressed over time. I’ve covered the topic of Zelda puzzles before in Riddles, Puzzles, Games, and how Zelda puzzles are closer to Riddles than necessarily Puzzles, because they tend to use scripted sequences wherein players make an inference from a hint they are given to progress more than necessarily interacting with a discrete system of logic. I have also criticized this type of design in Nuzzles: Not a Puzzle.

We can see more of Aonuma’s thought process in this interview where he explains how he switched the direction of the series to be more puzzle oriented than it used to be:

――After hearing what you said, I think the action RPG element, fighting against the enemy actually stands out more.

Aonuma:

So if we think about when it was that solving puzzles became the key element of the game. It is probably from “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (LOZOOT)”.The reason is because I was in charge of designing every dungeon in “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (LOZOOT)”. At that time, I thought I wanted to make puzzles in the game. It was not like Mr. Miyamoto asked me to make it or it was decided that LOZ was a game with puzzles and battles.

――So what you are saying is, the puzzles in LOZ were just pure coincidence as Mr. Aonuma did what he wanted to do at the time when making 3D LOZ, right?

Aonuma:

Yes, if you look into the order of things. I was told to “think about dungeons,” but was never told “to think about puzzles.” So what was the reason that we did? It was done because I love surprising people and I also like puzzles. So I thought, ‘It would be fun if the dungeons were full of puzzles.

And there you go. The prior direction of the series was directly remarked to be “action RPG”, and the new direction under Aonuma’s helm was “puzzles”. So how did this direction change for Breath of the Wild, resulting in it being such a wild success?

Hidemaro Fujibayashi (The Zelda 1 Fan)

Hidemaro Fujibayashi was originally a Capcom employee. While he was with Capcom, he directed The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Seasons, and Oracle of Ages. These games were originally pitched to Nintendo as a remake of Zelda 1, but were expanded in scope until ending up as 2 games for the Game Boy Color system. Oracle of Seasons ended up having more of a focus on combat, while Oracle of Ages had more of a focus on puzzles, in the style of the recent Ocarina of Time. Much of the Zelda 1 inspiration still shines through in the design of Oracle of Seasons however, as can be seen in the map layout, which is similar to Zelda 1, and the bosses, most of which are reused from Zelda 1. In short, Fujibayashi is a huge fan of the original Zelda, unlike Aonuma, who isn’t.

Following the Oracle games, Fujibayashi was transferred over to work at Nintendo, becoming Aonuma’s Protege. He would direct Zelda: Four Swords, Minish Cap, and Phantom Hourglass before eventually becoming the director of a 3d Zelda title for home console: The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword.

I didn’t like Skyward Sword, and most people didn’t end up liking it either, as indicated by lackluster sales compared to Twilight Princess.

It was the Wii’s first game using the Motion Plus feature, but the way this manifested in the actual game was lacking. Fans were excited to see the next evolution of motion controls, or a game that actually integrated motion controls into sword-play in a realistic sort of way for the first time, and what we got was a game where you could slash in 1 of 8 directions, and stab forward, with enemies that would telegraph which direction they were blocking, and you simply slashed from the other direction. This wasn’t a control style that couldn’t have been accomplished on a regular controller, nor was it one that was especially tactically interesting. Twilight Princess may have merely mapped the A button to a waggle of the Wiimote, but Skyward Sword didn’t provide us with much different, given that all of the slashes have roughly the same physical properties (range, speed, recovery, power) as each other, just a different directions.

Skyward Sword is where I fell out of love with 3d Zelda. I bought it, and Dark Souls on the same day (after having thoroughly enjoyed Demon’s Souls), and noticed that I was playing Dark Souls all the time, while barely playing Skyward Sword. I eventually hunkered down and beat Skyward Sword (I’ve beaten every 3d Zelda game, except Majora’s Mask and Tears of the Kingdom), but it was agony as I was barraged with Puzzle Jingles that played in mini-cutscenes, and Fi constantly reminded me that I had low health and my Wiimote batteries were running low. After I was sick of the game, I reflected on my experiences with the Zelda series before it. Was I actually having a fun time playing these games, or was I just going through the motions of playing them, and kind of just going along with game fandom hype? Liking the things that people told me I should like? My conclusion was that a lot of the time I spent playing these games, I was bored, but engaged. It was work, not really fun. I craved a greater challenge, but being a kid with only a Gamecube, I didn’t really have access to that, except in the form of Smash Bros.

We can look at the 4 big spikes in that graph above to determine which Zelda games really carried the franchise: Zelda 1, Ocarina of Time, Twilight Princess, and Breath of the Wild. From this we can see that a lot of games in the franchise had a rather tepid reception, except for these 4, that really connected: Zelda 1, which was foundational to the series; Ocarina of Time, which brought the series into 3d and told a serious hero’s journey style story with an adult link and a dark fantasy art style; And Twilight Princess, which also had a serious art direction with an adult link.

So given that these are the games that really connected with fans, why did so many other games not follow this direction? Again, it’s Eiji Aonuma, as shown in this interview:

The demo reel included a brief face-off between Link and Ganondorf, styled after Ocarina of Time. Ganondorf, armour-clad and cackling, loomed over an adult Link, who threw his shield aside to meet his two-handed strike. Nintendo fans could barely contain themselves.

Not so for series director Eiji Aonuma. He straight-up hated it. “I saw that movie and I thought, ‘No, this isn’t Zelda. This isn’t Zelda at all,’” he says. “I felt like this wasn’t what I imagined Zelda to be. It wasn’t the Zelda I wanted to make. That video clip didn’t actually contain any big surprises. There wasn’t any kind of revelation going on. It was more like a continuation of the previous version.” To me at the time, I say, it looked like a scene from Ocarina of Time, but better looking. “Yeah,” he smiles. “That’s right. I wasn’t interested in it at all.”

Unsurprisingly, Zelda: Wind Waker garnered a negative reputation from audiences for being childish, creating a division between the general gaming audience, and Zelda fans. Facing this, Nintendo was forced to get serious with the franchise, and made Twilight Princess. This is reflected in this interview:

Jason: Along that lines, though, we obviously do have a very active user base that likes to voice a lot of their opinions about the Zelda series. They may not know whether or not you guys look at what they say – which I would love to believe that you do, because we care. And I’m just wondering: what is the largest change, or the most important change, that you’ve made to the Zelda series as a whole because of feedback from fans?

Aonuma: Hmm… I think the project that reflects our reaction to fan opinion is probably Twilight Princess. The incentive for us to create that different version of the Zelda universe was certainly as a result of The Wind Waker criticism that we received. Fans were saying that it wasn’t what they were looking for, it wasn’t what they were hoping for, so that’s why we went with this different graphic presentation. So I think that’s probably the one, the biggest change that we made.

I still remember eight years ago at E3 when we ran that first video of Twilight Princess. It was received very well; there was a standing ovation! So I still remember that moment very well.

“The incentive for us to create [Twilight Princess] was certainly as a result of The Wind Waker criticism that we received.”

The New Era

Following the failure of Skyward Sword and later, the Wii U, Nintendo once again had to get serious, especially for the launch of their new system: The Nintendo Switch. More creative control was handed over to Hidemaro Fujibayashi, and this time the project started with a pitch:

Internally, Nintendo loves playable pitch prototypes. And of all things, Fujibayashi’s pitch for the future of Zelda was made in the style of Zelda 1. For the first time in many many years, Zelda was going to be an Open World Action game, in line with the original. The game was going to have a focus on action combat instead of puzzle solving. Eiji Aonuma remarks in an interview: (Emphasis mine)

Actually, we made it possible to attack the obstacles with many methods in this product. In the existing “LOZ,” if the player clears the stage by going up to the wall or the foot of a mountain without solving the puzzle, then it becomes a bug. Of course, there were no stage that the player could go through without solving the puzzle in the existing “LOZ” and [any such instances were] eliminated in the debugging stage.

However, we decided that “we need[ed] no puzzles for this LOZ.” So it is okay that the player clears the stage by just climbing up the wall or the foot of the mountain.

FINALLY! After all these years of puzzle-dominated Zelda, the series was back in the hands of someone who actually liked the first game, and it was finally focused on combat and non-linear exploration rather than puzzles and cutscenes!

Is Breath of the Wild perfect? Obviously not. I think that Nintendo doesn’t really understand how to make melee combat still (funny how my predictions for the combat mostly came true, and didn’t really change for the sequel). Much like Mario Odyssey (which was not directed or overseen by Shigeru Miyamoto), I think Nintendo is having an internal shift in their development leads, and their game design practices. The GDC talk for Breath of the Wild mentions Multiplicative Design, which very much ties into what I consider to be depth.

BotW advanced Zelda‘s combat mostly by bolting on a few common features from other action games, like adding a “perfect dodge” to the side hops and backflip, a parry on the shield, and letting you jump cancel your attacks at any time. The hitstun on enemies is eerie as they’re frozen in place until the last hit of the string, where they’ll dramatically be knocked down. There are some neat combat montages for the game, but it’s questionable how practical or resource efficient many techniques are, when enemies have fairly simple and “cheese-able” patterns overall.

BotW‘s big innovation to melee combat really is incorporating First Person Shooter “Ammo” into a melee combat game. The durability of weapons is like your stock of ammo. This means combat is largely a matter of investing resources wisely or poorly. Will I get a better weapon for winning this encounter? Can I win this fight using the environment to avoid spending weapon durability? Will it give me enough experience points to improve future weapon drops? (Yes, BOTW and TOTK both have a hidden Experience Point system.) Ironically, BotW has more RPG DNA than Zelda 1 did!

Of course, players responded rather negatively to the sole interesting part of BotW‘s combat system, because while they’re very comfortable scavenging for ammo or new weapons when they run out of ammo in Halo or another FPS game, they don’t like it as much when it’s a melee weapon disappearing into the ether.

What other Zelda is out there?

Coming back to the start, Zelda 1 was an open world action game, and this worked particularly well on the NES in large part because it was split into screens. There was a secret, and enemies, on almost every screen in the game! This helped create a dense world, where you were constantly engaged with the game, as opposed to many modern open world titles.

Another game that I really enjoyed for delivering on kind of the core “promise” of Zelda is Ittle Dew and its sequel Ittle Dew 2 (I’m suddenly surprised I never wrote reviews of these games. I give them a 6/10 and an 8/10 respectively). If Zelda’s core gameplay is Combat and Puzzles, Ittle Dew delivers by having simple direct combat, and real puzzles (including some difficult bonus puzzles) instead of the nuzzles that the Zelda series is known for. Ittle Dew 2 is the only game I know of that replicates Zelda 1’s overworld format, being segmented into screens, thus having a consistent density of secrets and enemies as you explore.

Also, the Ittle Dew games helpfully let you skip every cutscene, and make it so dialogue with signs and NPCs are a simple pop-up bubble that doesn’t interrupt your ability to move around instead of shoving you into a mini-cutscene. The games have amazing UX. If you’re ever confused how a puzzle works, you can hit the gate blocking you, and it will point to whatever is necessary to open it, whether it’s a switch, or enemy.

I feel like God of War 2018 and God of War: Ragnarok are what you’d get if you tried to make a 3d Zelda game, but with a focus on combat. Rather than be a true open world game, GoW 2018 has a hub and spoke layout to its world, which extends into story missions, and sidequests, a lot like many 3d Zelda games. As you progress through the game, you gain various “dungeon items”, which allow you to interact with features of the world you’ve previously seen lying around, meaning you can backtrack through areas you’ve cleared to collect things, or access new parts of the world for the story.

I like to jokingly refer to GoW 2018 as the best 3d zelda game. I have been writing a review of it, but I never quite finished it, and it’s fell onto the backburner in recent years (maybe when Ragnarok comes to PC and I finally get to play that). If Ittle Dew delivers on the promise of 2d Zelda, God of War 2018 delivers on the promise of 3d Zelda.

The Identity of Zelda

A constant topic in interviews with Miyamoto, Aonuma, and other Zelda developers is questioning what the “essence” of Zelda is. Aonuma never seems to be able to put it into words, but Miyamoto has this answer:

Iwata: I see… Miyamoto-san, when you’re asked what defines Zelda, how do you normally respond? Can you give a definite answer?

Miyamoto: Sure. For me, what makes a game “Zelda-esque” is actually much the same as what makes a game “Mario-esque.”

Iwata: And what might that be?

Miyamoto: Basically, I think it’s the way these games respect our customers’ intelligence. When our customers play our games, they will do all the logical things they would do as if they were doing something in real life, and if there’s something that does not seem to be working the way they should be, they’ll get upset. […]

Iwata: Ah, I see.

Miyamoto: It’s fine if someone really likes Zelda’s story: in fact it’s great. But if a person like that starts to work on developing a Zelda game, they won’t necessarily be an ideal match for the project. Something else that is vital to Zelda is that everything fits together seamlessly. This isn’t easy to explain, but what I mean is that with all of the ideas in the game tightly woven together, the various elements of the game will perfectly complement the terrain and scenery. The balance of “sparsity” and “density” in the game works really well. This is something that’s important in Zelda. […] Putting it another way, perhaps it’s controlling the balance of “sparsity” and “density” that actually makes a Zelda game. Maybe this isn’t limited to Zelda… Maybe it’s the “Nintendo method” of making games…

Iwata: What you mean is that it’s the “Miyamoto method” of making games!

I’m not sure this is necessarily any more clear than anything Aonuma says, but it might be worth asking, do Aonuma’s games respect the customer’s intelligence?

I don’t tend to put a lot of stock in game design buzz phrases like, “respecting people’s intelligence,” because I think that’s kind of subjective, and I’d rather have a fun game that disrespected me than a boring one that didn’t explain anything.

The thing I magnetize to in the clip above is how long each of those mini-cutscenes are. First, the player needs to step through a door, then watch a mini-cutscene of it opening, Link walking through, then the camera following after as the door closes. Then they need to sit through a mini-cutscene where it laboriously shows the order of the candles, holding on each candle for emphasis. Then they are prompted to optionally engage with a mini-cutscene where the king of red lions explains that you should pay attention to the candles. Then there are 2 more door cutscenes, followed by a cutscene showing what order to hit the switches in, and finally a cutscene of the warp gate being activated. That’s 6 mandatory cutscenes and 1 optional one! On top of that, you’re not allowed to skip any of these! That’s abysmal UX!

At their roots, Aonuma Zelda games are like Adventure games more than anything else. This becomes obvious if you look at the “Trading Sequence” quests across the games. A trading sequence is a long quest wherein you collect an item then trade it with many many other NPCs over the course of the game, before ending up with a reward, usually a more powerful sword. At their core, trading sequence quests are basically just visiting a number of nodes spread across the world in a specific order.

It was asked in my discord, what can be done to make these quests more interesting? It was suggested that maybe there’s a time limit on them. I suggested making them like the Fragile Flower sidequest in Hollow Knight. However, doing either of these things, or adding additional challenges or sidequests to each step, would be rather unfair, or change it so much that it wouldn’t really be a trading sequence anymore.

It would only be fair to have a time limit or to restrict you to take no damage and use no fast travel if you knew all of the destinations from the start, and then it wouldn’t really be a trading sequence quest anymore. The quest is intended to have some serendipity to you running into people who are seeking a specific item and offering a different one in return for it. Within the constraints of the trading sequence quest, the only thing you can really play around with are: 1. How clearly each item is signposted by each NPC and 2. The narrative of how each item is useful to each participant in the sequence. At that point, you just have Adventure game design. There’s no action component.

And if you look at the structure of 3d Zelda games more broadly, like if you were to read a strategy guide for Ocarina of Time or Majora’s Mask, this is what a lot of the structure of the game is: Finding items, and using them on the places that receive them. Compare this to a walkthrough for Dark Souls, and notice how this guide is instead giving you tips for all the core gameplay encounters you’ll have, but it can’t tell you exactly how to handle each of these.

The Future of Zelda

It’s fairly common to suggest that Zelda should learn from Dark Souls, or to say that Dark Souls carries on the spirit of classic Zelda. Both Skyward Sword, and Dark Souls 1 released around the same time, so the comparisons are easy to make. One game has a revolutionary combat system that shaped the way dozens of other AAA games designed their combat for the next decade, while the other flopped. Dark Souls “respects the player” enough to include real secrets that you’re capable of missing, rather than barraging with you “secret” jingles in mini-cutscenes for non-optional content. If the core concept of the series is action and exploration, Elden Ring delivers on that promise, and it’s difficult to imagine how Zelda could do that without simply treading in the footsteps of its competitor.

Until BotW hit in 2017, it wasn’t really clear exactly what 3d Zelda could look like besides the same tired Aonuma formula. And now after Tears of the Kingdom, Fujibayashi is saying that he has no plans for DLC, because he thinks this cycle of Zelda games has been completely explored, and the next game will be something new, something without Ultrahand. However, it’s also been stated that Open World is going to be the norm from here on out and the previous style of 3d Zelda is not coming back.

I think that in order for the series to improve, it needs to focus on its core gameplay. For Zelda, that’s its action combat, and exploring a world. I would submit that another part of Zelda‘s core is “Tool Use”, such as bombs, arrows, or fire rods. You fight using your sword, and you use tools alongside it. This is something Breath of the Wild focused hard on, and Tears of the Kingdom was more lax about. Obviously other 3d Zelda games had tools, but they were mandatory puzzle solutions, rather than an optional part of your strategy.

Another big difference from the 2d games versus the 3d ones is “pushback”. When you hit enemies, they would be knocked out of your range, and you could frequently run after them to hit them before they recovered. Larger enemies would push you back if you slashed them. If Zelda wants to build an action-focused combat identity without copying Dark Souls, I think this is a solid lead: Fast slashes, and high pushback on hit. This could yield something somewhat similar to Smash Bros in execution if done right.

I think the combat gauntlets at the end of Zelda 1 and Link to the Past show what’s possible when the games aren’t pulling any punches. They’re willing to throw a variety of enemy types at you, and there’s a lot of dynamism to following how they move across the room, and managing each type of enemy. I would like to see more of this type of dynamism in future games, but I worry that they’ll struggle to capture it in 3d, especially given their track record with melee combat. BotW and TotK didn’t feature a wide variety of attacks or enemy behaviors, and it seems unlikely that the devs will really get the picture by the next game.

Overall, I’m curious as ever to see where the series will go, and see if it will improve compared to its contemporaries, or try to be something different altogether, like TotK did. Nintendo tends to hate iterating on prior games, preferring to come up with new mechanics and gameplay styles whenever it releases a sequel (unless something is too big and consistent a money-maker to gamble on, like Pokemon, Smash Bros, or Mario Kart). It’s entirely likely that the next game will once again try to return to the franchise’s roots, or that it will base the whole thing around another stupid gimmick. We’re likely to see in about 4-6 years. At least things won’t go back to how they were before.

Love the article but from the first bit of it, Miyamoto didn’t create Ice Climbers, Kenji Miki did. It was made by Nintendo R&D1, while Miyamoto was at R&D4 (later EAD)

He also didn’t direct Zelda II, Tadashi Sugiyama and Yasuhisa Yamamura did. It was made by R&D4 though and he was Producer on Zelda II, like with LttP.

I think his only directing jobs were Donkey Kong, Jr., 3, Mario Bros., Devil World, Kung Fu (NES port), Excitebike, Super Mario Bros, Lost Levels, 3, 64, The Legend of Zelda, and some NES Light Gun games.

LikeLike

Thanks! I’ll revise next chance I get.

LikeLike

I’ve updated the article, and also fixed a broken link. Thanks again!

LikeLike