So previously I’ve taught you How To Perform Fighting Game Motions, now lets learn how developers coded them. As far as I know, nobody has documented how to do this before, and it’s essential for anyone making a fighting game, or anything like a fighting game.

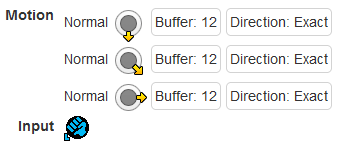

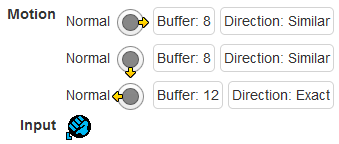

There is a website called SFVSim that catalogues change differences between versions for moves in Street Fighter V. This includes a lot of data on each move, including the input requirements.

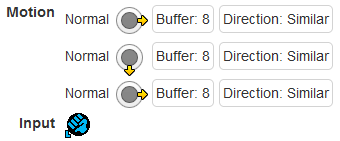

This is extremely helpful for determining the logic involved for these motion inputs. The buffer on each direction determines how much time in frames is allowed to elapse before the next input is provided, or the motion becomes invalid. In other words, it determines how quickly you need to do the motion, and how much time you have to press the button after you’ve completed it.

Buffering

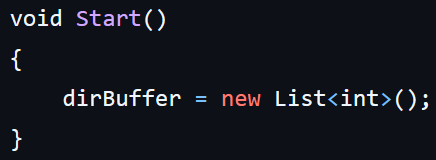

The first step in making a system like this is to first build a buffer that holds all recent directional inputs. You can read my buffer code here (this was coded in Unity).

The directional buffer here is a list of integers. I’m using numpad notation for these integers to store the directions that are being pressed.

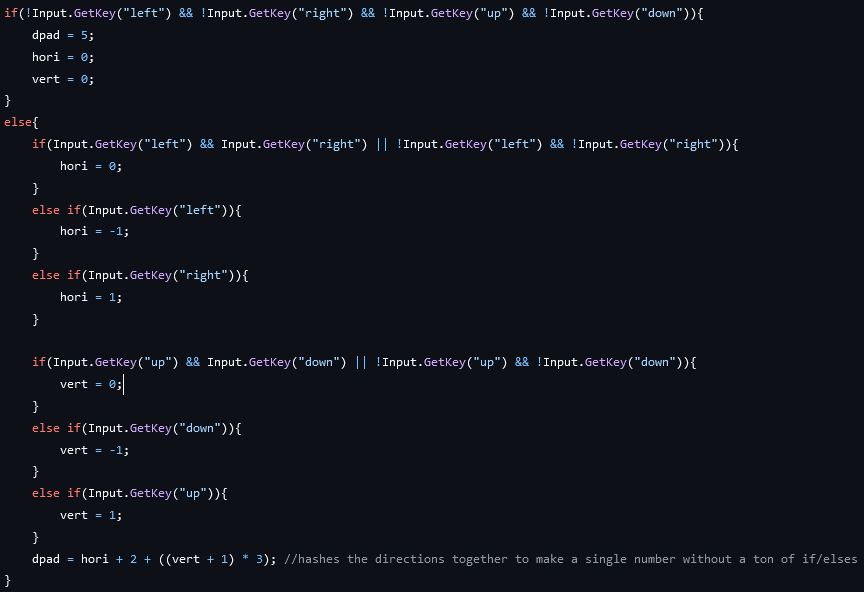

In order to determine what combination of inputs produces which direction, I have this code that takes in keyboard presses and determines the correct output:

The first If block determines if no key is being held, and sets the current direction to 5, neutral.

In the Else block, I’m trying to determine the current direction in terms of a horizontal component, and a vertical component, and then turn that into a composite direction. The first check is to see if both left and right are being held, or neither left or right are being held. These will produce a neutral horizontal component to the input. I repeat this process with up and down to determine the vertical component.

I could have done a complicated series of if/elses to determine which way this is pointing from the components, but instead I looked at the numpad, noticed that the bottom row counts 1, 2, 3 and mapped the horizontal component to that. The next two rows also count that way, so I just need to add 3 or 6 to move up a row. I could have simplified this math by assigning the horizontal component 1, 2, 3 manually, and assigning the vertical component 0, 3, 6, but that makes it less readable what those components are doing, and makes it harder for you to use those components for other purposes.

Finally, we insert the direction into the buffer, starting by culling old inputs from the end of the buffer and then inserting the new input at the start (depending on the data structure used, this can be a mildly costly process, but for a single list, this isn’t a huge deal).

There is a check here to see if any keys were pressed or released this frame, otherwise it will insert 5, a neutral input. This isn’t strictly correct, but it ensures that we’re only capturing inputs when the dpad moves, avoiding letting the same direction count for multiple directions in the input, without requiring us to implement a more complex detection for a change of direction when we’re evaluating the motion.

Motions

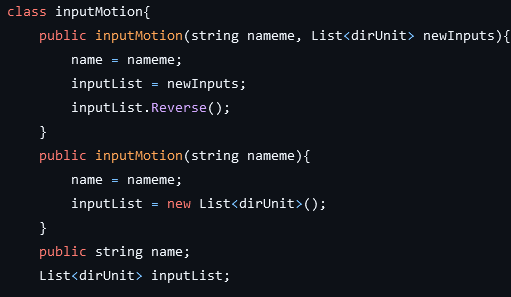

Next is the InputMotion class, which defines and stores a particular motion, like Quarter Circle Forward, and has an API for creating and editing these motions, and checking whether they’ve been performed correctly.

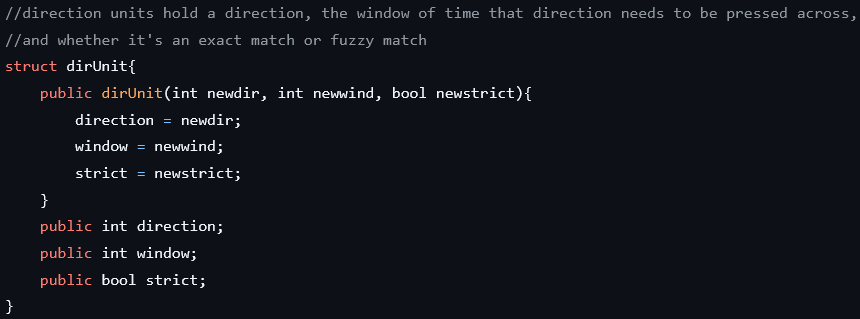

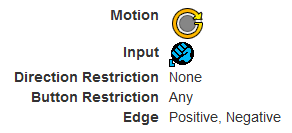

The first step is storing directions. Directions have 3 components: the direction, how wide the buffer window is, and whether it checks for exactly the direction, or allows the surrounding directions. A constructor is provided so that you can instantiate the struct and immediately assign it values.

You can compare this implementation to the motions in Street Fighter V.

The InputMotion class consists of a name, and a list of the direction structs we just defined; the directions in the motion input. It has a constructor to either make an empty named InputMotion, or pass in a list of directions directly, then reverse it for reasons we’ll see later.

The Add() method allows us to add a direction to the motion input. I reverse the list twice here, and I definitely could have just inserted it at the start of the list, or crawled the array from the end instead of this silly procedure. The cool thing is, Add() returns the instance of InputMotion that is being acted on when it finishes, allowing you to chain multiple Add()s in a row, defining a whole motion in one line of code, like this:

In these lines, we’re making an empty named InputMotion, then chaining multiple calls of the Add() method to build a motion.

Checking

Finally, lets see how the InputMotion checks whether or not an input has been executed correctly.

checkValidInput() goes through each direction in the InputMotion’s list of directions backwards, then scans backwards through the buffer to see if there is a matching direction. It uses curInput and bufferpos to keep track of its place in the input list and the directional buffer across recursive function calls. So when it’s first called, it starts at 0 for both of those, and whenever it finds a matching direction, it will call itself for the next direction in the list, picking up where it left off in the buffer.

To run through this, for a QCF (236, ⬇↘➡), when the punch button is pressed, it will check back through the last 12 frames to see first if 6 ➡ was pressed. If it was, then it will call checkValidInput() again, this time looking through the next 12 frames to see if 3 ↘ was pressed. If this succeeds then it will repeat, checking 2 ⬇, and if that succeeds it returns true for a success. In this way, it checks backwards from the point you press the input to see if all the inputs leading up to it would produce a valid special move.

If checkValidInput() runs out of directions in the input’s list, it will return true, indicating the input was successful. If it does not find a matching direction in the buffer for the length of frames it’s asked to check across, it will return false.

The logic for checking directions will compare a direction from the buffer, curDir, to one from the input list, targetDir, and will either do an exact comparison, or a soft comparison if strict is set to false.

I didn’t implement facing direction into my demo, but the logic basically just checks whether you’re holding a left or a right direction, and flips the input by adding or subtracting 2 (because 1 and 3 are opposite directions, as are 4 & 6, 7 & 9).

The strict comparison is simple enough. For the fuzzy comparison, I manually wrote out the adjacent directions for all 8 directions and return true if the current direction is any of those.

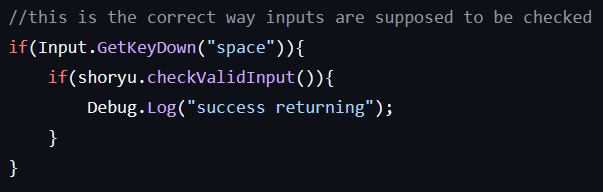

Finally, we check the input by just calling checkValidInput() when the associated button is pressed. I should probably be handling this through some type of event or delegate system, so that I can store the associated button directly in the input motion at the point of creation, but for a proof of concept, this is fine.

You might notice that I’m not passing curInput and bufferpos into checkValidInput() when I’m calling it. This is because I have another checkValidInput() method that calls checkValidInput(int, int), so that you can’t accidentally feed it bad data elsewhere.

Shortcomings & Future Functionality

This approach to input checking is incomplete, and individual games have particular quirks to the ways they check inputs, which makes more or less sense depending on the game.

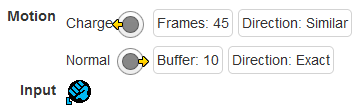

First, I don’t have a real solution to charge and 360 inputs. Here’s what these look like in Street Fighter V:

Some games have timers for charge inputs that keep track of them outside of the input system, such as 3rd Strike. Street Fighter V checks that there are 45 or more back inputs in a row. Additionally, Street Fighter V flips inputs in the buffer based on facing direction, whereas I’m flipping them in the checker, which is how Under Night In-Birth does it. This means in SFV, it’s possible to frame-perfect continue a left-right charge input when someone jumps over you if you can move quickly and accurately enough. And in Under Night, when you cross through an opponent, your forward-back charge will become a back-forward charge, enabling Vatista to 66C through her opponent, then cancel into [4]6A for a combo.

360 inputs have their own logic governing the input that is outside of the charge system. I approximated this by making 360 and reverse 360 motions manually, but other games have more robust detection for this, starting in any direction, going in any direction. Most likely it’s just checking if the buffer window contains all 4 directions, then that they’re ascending or descending, but that’s still unique logic.

Finally, one of the quirks of SNK games is their input “long-cuts”, where you can do a longer version of a move to force a certain interpretation, ignoring normal special move priority.

The Dragon Punch motion (623, ➡⬇↘) has priority over the quarter circle motion (236, ⤴) typically. It’s a more difficult move to perform and it overlaps with the QCF (a common way to perform DP is ➡⬇↘➡), so they want to ensure that you get the DP when you do perform it. This means it can sometimes be difficult to walk forward, then do a QCF. You accidentally get the DP instead.

In SNK games, you can do a half circle forward (41236, ⬅↙⬇↘➡) in order to force a QCF, even after walking forwards. Some people call this a “long-cut”. The way this works is, if the interpreter finds a direction that is not a part of the motion it is checking as it reads the buffer, it will fail the input check. So 64236 ➡⬅⬇↘➡ is not a DP, because it has 4 ⬅ in it, even if it otherwise meets the timing requirements to parse as a DP. However, it is a valid Quarter-Circle Forward, because the last 3 inputs are 236, ⬇↘➡.

This can be implemented by adding an additional check to checkValidInput(), which checks the current direction against each input in the list, and if it doesn’t match any of them, it returns false, failing the check completely. This is more computationally expensive, but the whole thing is pretty small-beans relatively speaking compared to just about any graphics calculation.

Conclusion

Input reading is a problem that stumped me for many years, and I had to improve a lot as a programmer before I could figure it out. There isn’t any good documentation about how to accomplish this that I could find online, so when I finally cracked it, I wrote my own.

This could be extended to 3d games or top-down games by simplifying analog stick inputs into the 8 directions, and mapping them relative to lock-on or facing direction. That may require more complex and unique logic, along the lines of the 360 logic I described earlier, which is more ambivalent to the starting direction and the direction of motion.

This system is similar of how i implemented in a recent comercial fighting game, but it can be heavy to a certain portable console, and i have to change the system to another approach that checks the input for every move each frame and going forward using an index for each move instead of going backwards into the buffer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That makes sense. I did a version that checked forward when I was first working out the algorithm, then I made a version that scanned backwards when I improved at coding.

LikeLike