Hollow Knight: Silksong has revived an annoying line of discourse about “Artificial Difficulty”. Artificial Difficulty is ostensibly things that make a game appear more difficult, without actually engaging player skill. However in practice, most people claiming that a game has “Artificial Difficulty” are just complaining that the game is too hard for them, and this isn’t their fault, but the game’s fault. It did difficulty “wrong” in some way.

If we were to take the language of Artificial Difficulty at its face, then we’d consider whether or not a game is engaging in a fair test of skill with you. And in this way, some obstacles in Silksong aren’t fair actually, such as the bench in Hunter’s March that is rigged with a trap, which will damage you when you try to sit on it (I fell for this one). There is a very short tell, the bench depressing like the pressure plate traps in the prior section, giving you a brief opportunity to get off the bench and dash away. Disabling the bench trap requires going through a hidden tunnel and pressing a hidden switch. Silksong has a number of moments like this, which I believe were intended to be funny, because I found them funny and I know other people did too.

The Kneejerk Complaint

However, most people I see invoking “Artificial Difficulty” aren’t engaging with the topic this honestly. They aren’t measuring human reaction time in comparison to the game’s telegraphs. They aren’t considering fair communication to the player. They aren’t differentiating input versus output RNG. Instead, most complaints about artificial difficulty are along the lines of, “Enemies have too much health” “Enemies deal too much damage” “Checkpoints are spaced too far apart”. Rather than recognizing that these contribute to the difficulty of a game, and admit that the game is simply too hard for them, people accuse the game of having an illegitimate form of difficulty. This is a type of Scrubby bad sportsmanship. Blaming the game instead of yourself.

I ran into a situation like this when I played and reviewed Cloudbuilt a little over 10 years ago (sadly, the review has been lost to time). One of the final challenge levels was too hard for me. I couldn’t complete it and I admitted as much, while giving the game a glowing recommendation. I got teased a little for this in the comments at the time, but I don’t regret being honest about my skill level.

Blaming the game instead of yourself is a common kneejerk response to encountering a hard game, especially if the source of the difficulty is something that feels arbitrary and easy to adjust, such as damage numbers or checkpoint density.

Masocore Difficulty

I’ll be perfectly honest, I had this type of kneejerk response to Super Meat Boy way back when it came out. I got frustrated repeating sections so precisely and I still don’t really like Masocore games to this day. This was a formative enough moment for me that it helped inspire my theory of Depth. I wanted to say, “This is bullshit. This isn’t REALLY hard!” but I ended up taking it in a more levelheaded direction: Challenge alone doesn’t make a game good.

Edmund McMillen talked about his approach to difficulty in 2010, basically saying, “A lot of older platformers have had health, lives, and game overs across fairly long levels and worlds and moderately difficult individual obstacles to create difficulty. A lot of people nowadays don’t respond well to that, so I chose to go in the opposite direction by creating short levels with intensely difficult obstacles that you can repeat instantly without game overs“. I think this is a respectable response to the games market of that time, even if I didn’t really like the approach that Super Meat Boy and other Masocore platformers took.

The article concludes with:

“Video games are exercises in learning and growing. The designer acts as the teacher, giving the player problems that escalate in difficulty, hoping their course will help them learn as they go, get better, and feel good about what they achieve. When you are trying to teach someone something, you don’t punish them when they make a mistake. You let them learn from it and give them positive reinforcement when they do well.”

The Punishment is the Reward

I don’t agree with this. I think that the conception of “punishment” that we have for games is a little too rooted in the real-world analog of reinforcement learning. If I fail an exam at school, I will learn more if I’m allowed to repeat the exam. This is not the same as being beaten for getting a bad score, or being beaten whenever I get a question wrong. When I get a game over in a video game, I am not suffering physical pain. I have fallen from the top of Getting Over It’s mountain to the very bottom, and I have risen back up to complete the game over 100 times. These types of experiences can inspire emotional anguish, but I think that’s also one of the rich textures of video games. Video games, much like BDSM, are a voluntary activity that we engage in because we want to, and we have a negotiated relationship to opt out whenever we don’t feel like continuing.

If we look further at games as learning tools, we can see an analog to this in the Leitner Spaced Repetition system for studying. Sebastian Leitner proposed a method of using flash cards in order to study a subject, where you create a number of flash cards for a subject, and store them in a series of boxes. At first the flash cards all start in the first box, which will be quizzed often. When a flash card is answered correctly, it will be moved over to the next box, and then the next. As a flash card graduates to further boxes, it is quizzed less frequently. Failure to answer it correctly will demote it to an earlier box, making it more frequent in the rotation. In other words, a student using this system will be quizzed frequently on questions they struggle with, and progressively less frequently on questions they can answer reliably, until they can successfully answer all the questions in the set. (In the past, I’ve proposed that action game bosses should distribute the probability of using each of their moves this way, and I still think it would be a great idea)

Instead of jumping to, “tweaking statistics to make a game harder is artificial bullshit!” we should consider: What is the actual effect of high damage, tanky enemies, and checkpoint starvation? Another way of framing these is margin of error, the number of successes required to pass each obstacles, and the range of obstacles currently being tested. If you look at it like an exam, you have a pass/fail percentage (you need to get above a 90% mark to pass the exam), each question (enemy/obstacle) has a certain number of parts, and the exam is of a certain length, and must be retried in its entirety when you fail. Video games are a lot more fair than typical school exams, because they give you the chance to retry as many times as you want, and there aren’t any real world consequences to failure.

We can also consider this from a probabilistic angle, because video games present obstacles sequentially, not in parallel like your typical exam. Lets say that you have a 50% chance to clear a given obstacle. This represents your current level of skill relative to the difficulty of that obstacle. If checkpoints are placed after each individual obstacle, then you can get through each obstacle in a fairly short amount of time, even though you’re not particularly good at clearing the obstacles. If you need to go through a sequence of 4 obstacles in a row, your 50% odds will get cut by half for each obstacle in that sequence, going down to 25%, then 12.5%, then 6.25% of overall success. In other words, when checkpoints are spaced more widely apart, you are tested more thoroughly on your consistency with each individual obstacle. In order to succeed overall, you need to actually raise your odds of success with each obstacle, instead of banking every small success you get and disregarding all the failures.

This is important: When you are forced to complete multiple obstacles in succession, you need to actually improve your skills in order to succeed overall. It is directly engaging your actual skills, instead of simply luck.

It is absurd to call this artificial difficulty when it is so fundamentally connected to the skill-building process. It is the thing that actually mandates that you build skill, that actually tests that you have built skills!

To give a weightlifting analogy, you have the amount of weight on the rack, the number of sets you’re going to perform, and the number of reps in each set. Obviously, the more of each of these you have and perform, the more difficult the workout is overall. One set of one rep with the heaviest weights you can lift is not a real workout. When building workouts, we tailor the number of reps and the number of sets to our particular goals, and to the challenge we want to take on. The common “Artificial Difficulty” argument is essentially stating that only the amount of weight matters, and not the sets or reps.

Masher or Master?

Classic God of War has a reputation as a more mashy action game compared to Devil May Cry, Bayonetta, or Ninja Gaiden. I have no idea how on earth it earned this reputation, considering just how aggressive and brutal the enemies and encounter design of that series is. Enemies are just as difficult to deal with, and require just as much precision in God of War as enemies in Ninja Gaiden Black.

One reason I can see however is the way that the game structured its difficulty modes. Across the first three god of war games, there is no functional difference between any of the difficulty modes except for how much damage enemies deal to Kratos, and how much he deals to enemies. This is literally the only difference. Enemies have no new behaviors, there is no new encounter design, no new placement of checkpoints or items. When you play on the easy difficulty however, you’re still going to be eating shit from enemies just as easily and commonly as on the hardest difficulty. Despite this, I’ve never heard anyone complain that God of War was a difficult game, and somehow it has a reputation as a mindless button masher of all things, even though GoW very strictly rewards and punishes proper use of its moveset.

Why is God of War regarded as a mindless button masher despite enemies being so difficult to dodge and defeat (like lifting a 200 pound weight)? Probably because on the easy difficulty, you take so little damage that you can tank hits through entire fights and still win. And on top of that, many times when you die on higher difficulties in the first game, it asks if you want to bump it down to easy, which irreversibly locks you into easy mode. It’s like being asked to do only one rep. You’re not asked to build consistency or improve at avoiding enemies and efficiently dealing damage to them. You can take many many hits before finally dying, and enemies only require a few to be defeated.

In other words, even though adjusting damage values can feel cheap or artificial, it has a massive influence on the actual difficulty of the game. In other words, how skilled you need to be in order to beat that game. There is also the connected topic of pacing (It feels boring to pummel an enemy with a lot of health after you’ve already solved the encounter), but people are far too quick to disregard simple damage values as a source of difficulty.

I had an experience moving from NG to NG+ of Dark Souls with the Four Kings boss. The added health and damage of the boss meant that I needed to learn a lot more about the behavior of that boss in order to win. Critically, that being close enough to one of the kings would cause the others to disengage. A simple change in damage values required me to engage in a more nuanced decision-making process with the boss behavior.

“THAT IS BULLSHIT!” (Blazing)

As players and designers, we shouldn’t be so quick to disregard a simple change that results in higher difficulty as being “fake” or “illegitimate” in some way. Every part of a game is artificial and arbitrary, not just how many hitpoints you have and how far checkpoints are spaced. This includes movement speed, the amount of tracking on attacks, the startup and active times of moves, spacing of platforms, and so on. All of these things are as just as artificial and just as easily adjusted as HP and damage values.

We should be questioning how these attributes create texture and variety across games, instead of simply insisting that a certain tool should never be used under any circumstances. How does application of this tool make our games more nuanced and reinforce the skills we want to teach?

I think that the inclusion of double damage enemies & attacks in Silksong, and making them as commonplace as they are gives the game a lot of texture and variety (Much like how a BDSM participant might compare thuddy and stingy pain from an impact toy). It means that some attacks are more impactful than others, and some enemies are scarier than others. It gives the designers room to play around with your margin of error. (Also, I really enjoyed the Bilewater runback!) If every enemy dealt only one mask of damage, then it would flatten the difference between bigger and smaller enemies, more and less impactful attacks. It would mean that you can apply the same amount of care across all enemy types instead of needing to focus harder and play more carefully when a double damage attack is telegraphed.

When we say, “That’s bullshit!” more often than not, we’re trying to protect our own egos, rather than honestly admitting to our shortcomings. We should be saying, “This game is too hard for me,” instead of, “This game is too hard for anyone! (because I’m having a hard time with it).”

It’s okay to criticize the way that a game is tuned. Some tuning values can be better or worse. This isn’t a simple issue with a single solution. There is a real conversation to be had about tuning and fairness in game design, but this isn’t it.

What are your thoughts on the original version of Promised Consort Radahn? Was he unfair or simply too hard? I don’t think I agree with what you said regarding checkpoints. There’s a lot that can effect a person’s chances of bypassing each obstacle. Your success rate isn’t as set in stone as the percentages you claimed. A person can actually perform worse, due to the tedium of repeating the whole process again and then just wanting to get it done with. That said I’m fine with checkpoints being spaced apart under certain conditions. I think Demon’s Souls mostly handled runbacks well, because the bosses were generally easy and the challenge came from the levels. But in the later Souls games, the bosses became the main source of challenge, so I think the runbacks being fizzled out as the series progressed was a good thing. I’m not sure how Silksong handles them.

LikeLike

I didn’t claim your success rate was set in stone. I actually said, “In order to succeed overall, you need to actually raise your odds of success with each obstacle,” the opposite of what you seem to think I said.

I didn’t actually finish the Shadow of the Erdtree DLC, I got tied up in other stuff and never got back to it. Looking through patch notes, I think the only component I’d label as a change to fairness is “Improved the visibility of some attack effects,” but I can’t really speak with authority here.

Making runback length inversely proportional to boss difficulty is an interesting heuristic. Of course, nothing says things have to be that way.

LikeLike

“We should be saying, “This game is too hard for me,” instead of, “This game is too hard for anyone!”

Or rather we should make statistical measurements. If the game is too hard for 60%, 70% or 80% of players, then, probably, it is unreasonably hard.

Also, what if someone buys a game, and it turns out, that they cannot complete the game, because their psychomotoric levels are insufficeint due to age or other constraints? Is this good game design, if obstacles are tuned in a way, that require reaction times of a healthy, well rested 20 years old on her good day?

LikeLike

Many of the top eSports performers are now in their 40s.

Game Center CX is a TV Show about someone who is incredibly bad at video games going up against tough classic video games, and winning.

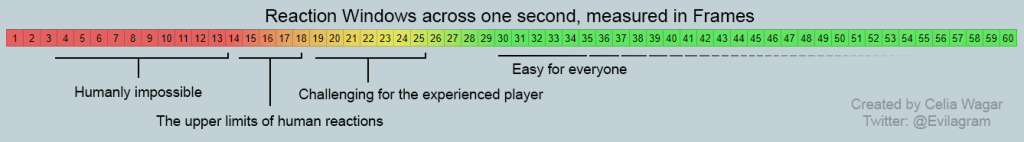

I generally advocate for reaction times tuned around 250ms as the baseline, the average human reaction time. That’s 18 frames at 60fps, and I usually recommend that games telegraph from 20 to 25 frames at minimum. And I do actually call out when games do not telegraph within this window. Silksong is INCREDIBLY consistent about telegraphing above this window, more than Hollow Knight even! It is an incredibly fair game that has reaction times that the vast majority of the population can reach. (I’m 33 by the way, And my average is 200ms)

Like the article concluded, there is a real argument to be made about fairness, but this comment isn’t it. If you want to argue that a game is unfair, then you should probably quantify that relative to average players, as I have. Are we having a conversation about actual statistical fairness or vibes?

Is “good design” making a middle-of-the-road product that optimizes for maximum sales?

LikeLike

Saw some folks complaining about enemy movements themselves being those sort of, I quote, “untelegraphed attacks.” (I can think of Anderson from the top of my head) I think they mean things like, say, the Pinstress sometimes jumping to the center of the screen after her estoc ground charge? It only really matters if you keep up your aggression, but it’s quite brutal the first time around, and its “mixing it up” quality with other options can really dampen your aggression—or rather, your breadth of options. Ambient, erratic mouvements can be mitigated by throwing a swing in there, it is effective at safeguarding against dashing into sprites thanks to pushback but some more “predicated” moves can be hard to react too. (Personally, I got around to love Pinstress, the fight is almost too much of the footsie game when she starts going crazy with those dashes whle charging the move + stun into fall from the arena into “who gives a damn, get robbed” was quite funny)

LikeLike

I found Pinstress to be really fair. She telegraphs all of her attacks, or they have predictable variations. Her thrusts are sometimes 2 or 3, but you can play around that pretty easily, and the start of the thrust pattern is telegraphed, so there’s no surprise.

The only attack that stuck out to me across the game as remotely unfair was Crust King Khann summoning a pillar that covered the bottom half of the screen, then jumping up at me while I was in the air above him. Obviously that was only unfair because he literally covered up the telegraph.

Skarrsinger Karmelita can also jump into the air and either lunge forward, or throw knives down, but you can beat this by staying grounded and reacting to parry the knives or jump away from the lunge. I got caught by it a lot because I would jump straight up to avoid the knives and get hit by the lunge half the time. I didn’t find a good non-parry solution besides staying far away, but there probably is one. I found her to be the hardest boss for me, and this was a big reason why.

Overall, Silksong is just an absurdly fair game, more fair than even Hollow Knight, which had some untelegraphed jumps that I felt were a bit unfair at times. It’s REALLY REALLY REALLY consistent about being fair, and I catch a lot of games for having unreactable attacks.

LikeLike

Right! It would be interesting to see you cover this game. I’ve found the critical reception quite frustrating at the moment. There’s some whininess and a lot of uninformed takes putting the game down for strange reasons — for example, someone claimed the game should explain contact damage biologically, and that without this, the challenge it creates is “an illusion.” Then there are the more blasé, almost cynical comments from action gameS intelligentsia on social media, particularly about its Metroidvania nature. Even when they’re impressed by aspects of the combat, they still tend to frame it as somehow “wasted.” (Although Boghog article on enemies was quite good, ‘found the boss one … sort of exagerated on how it traces the design to cogwork dancers, not totally unsound but forced ?) I know you’re quite busy elsewhere, fighting the good fight with courses and such, but hey — just some wishful thinking on my part.

LikeLike

I’ve been writing a review as I’ve been playing. I have a lot of notes. I’ve been sidetracked with other projects, but I’ll try to get that wrapped up as soon as I can.

Also, I included some examples from Silksong in my next course! Including cogwork dancers (I’m even building a heatmap of player choices over footage of the fight!)

LikeLike

What if I would never even begin to make a game if it wasn’t that hard?

Since a player usually needs a reason to use the tools they’re given, what if my dream game has mechanics that require a very high level of difficulty to be used to their fullest?

But I do think developers should be clear about the difficulty of their game however.

LikeLike

If that’s the case, then have fun with it.

LikeLike

I always get a little irritated when challenge in video games is compared to suffering. How are we suffering? Is it the ego? With most video games, especially mainstream games, it is a foregone conclusion that we’re going to beat the game. They’re often easy power fantasies that stroke our ego. Good job for beating this level or that boss. You did great once again. You are the best gamer in the world.

But then some difficult niche game comes along and says, no, you actually suck, and if you want to beat this, you’ll have to get a lot better. The only thing that’s suffering here is the spoiled ego. Or is there anything else?

We don’t use this kind of language for other, non-video game activities. Learning to play a musical instrument in order to perform a song flawlessly is a lot more difficult than beating Silksong. So many hours of practice required, but nobody would call it torture or masochism. Or, for example, when practicing pool, a common challenge that players will do is attempt a 100 ball run in straight pool (very tough for amateur players). If you miss a ball, you have to start from 0. What a time loss! But I’ve never had other players come to me saying, “why are you doing this to yourself?”, “this game is torture”, etc. It’s just a normal practice routine. But when I play Kaizo Mario hacks, I’m a masochist and a lunatic. Thanks, I guess… This even comes from people who play these games themselves, and it’s so weird to me. Or maybe I’m just stupid.

There is a Kaizo streamer who also plays the guitar, and he compares learning and beating a Kaizo level to learning and performing a song with the guitar. One is normal. The other is torture, apparently.

LikeLike

I think something people often miss about runbacks is that, if a game is truly great, repetition will not be a chore. My favorite arcade games are like this for me; I’ve put 50+ hours into Ketsui so far even though it’s only a ~30m game and yet it does not cease to be thoroughly enjoyable every time I play it. Even though at this point I only need to make small routing refinements and develop my intuition about certain sections more, survival runs are still a blast because the core gameplay is (for whatever reason)fundamentally engaging and has enough organic variance that I never autopilot, and never feel safe.

In the end, runbacks only “punish” you by making you play the game more. And if you can find ways to appreciate and hone in on the intrinsic fun of a given games, runbacks are really not that bad. In Silksong what made runbacks much more fun for me was learning to speedrun the route back – especially in Bilewater.

LikeLike