Note: I wrote this up 5 years ago and intended to publish it, but I guess it got lost on the cutting room floor. My bad!

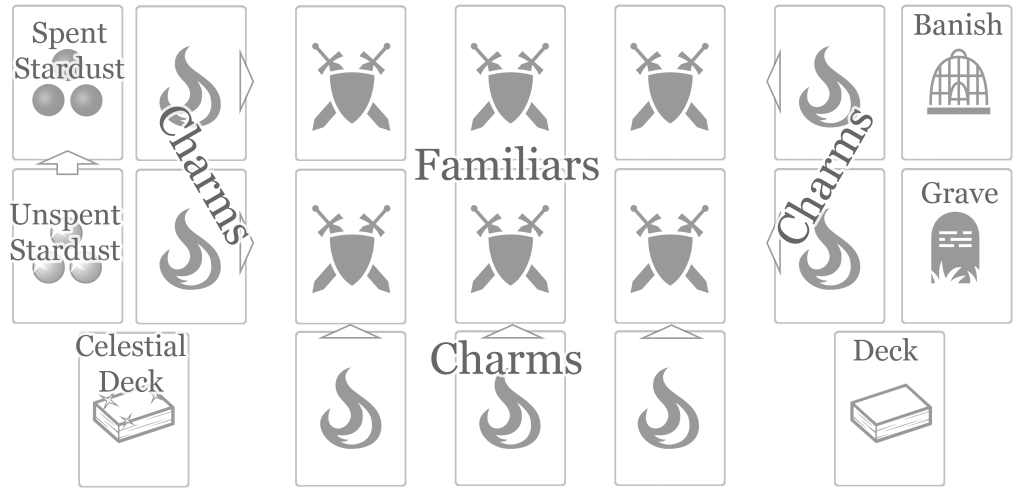

In Witcher 2, you have 2 swords, steel and silver (for humans and monsters respectively), and 5 spells you can cast: Aard, Axii, Igni, Quen, and Yrden.

Aard and Igni are projectiles, dealing damage/stun on impact. Igni deals more damage and burns the target for damage over time. Aard knocks the target back, stunning them, knocking them down, or dizzying them, setting up for a 1-hit kill. Quen is a shield that will block 1 hit’s worth of damage. Axii will convert one enemy into an ally temporarily, but needs to be channeled over time and has a chance to fail. Yrden places a trap on the ground that will stun an enemy who steps on it, holding them in place until it wears off or they are hit out of it. There are upgrades to each of these, Aard and Igni gain range and area of effect, Quen can reflect damage back onto opponents, Axii buffs the opponents you control, and Yrden lets you place multiple traps.

Almost every enemy in the entire game follows a similar template, they run at you, do attacks straight ahead of them, will not rotate while performing attacks, sometimes block moves that hit them from the front, and you can get behind them to deal double damage to their back.

This means fighting enemies is generally a process of rolling around them to get to their backside and hitting them for as much as you can. This can be accomplished by baiting them into doing attacks and moving while they’re occupied. This method of play, rolling behind enemies to backstab them with Quen shields up, is how all the best players play the game, and encouraged by the game design on multiple levels.

Continue reading →